Editor's note: All opinions, columns and letters reflect the views of the individual writer and not necessarily those of the IDS or its staffers.

I’m writing on learning of the late-August “hiatus” (without any renewal date) of the Indiana University Honors Program in Foreign Languages. This action follows several measures by the Republican supermajority in the legislature that undermine the state’s legacy of educational and economic outreach to the world. One of these measures included a new minimum threshold for degree majors, slipped unannounced into the state budget bill in April, effectively ending more than 400 programs across the state, including 116 at IU Bloomington alone, of which the worst hit were four dozen foreign language and cultural programs. IUHPFL also landed on the chopping block.

When I graduated from North Central High School in spring 1966, I felt fortunate and reasonably well prepared to enter the most challenging and competitive of academic environments. Among the educational laurels I had accrued, besides top grades, was a coveted “5” on the French language Advanced Placement exam. This last, I knew, was directly due to the experience I had enjoyed under IUHPFL’s auspices in the summer after my sophomore year. Under the discipline of a two-month no-English pledge, 30 other high school students and I lived with French families in the town of Saint-Brieuc, Brittany, a region in France, and a place I came to see as proud of its own traditions yet eager to show appreciation to visitors whose fathers had helped liberate their country a scant 20 years before.

Despite carrying with me an “official” letter from Indianapolis Mayor John Barton greeting his counterpart in Saint-Brieuc, I had little idea at the time how a program like IUHPFL fit into the larger vision and ambitions of the state and its flagship university. However, the language program comprised only one part of a dynamic, multi-faceted social and economic outreach of Indiana-based institutions to the larger post-war world. Under the leadership of IU President Herman B Wells and his successor, Elvis Stahr Jr., IU’s influence expanded abroad even as the university welcomed foreign students.

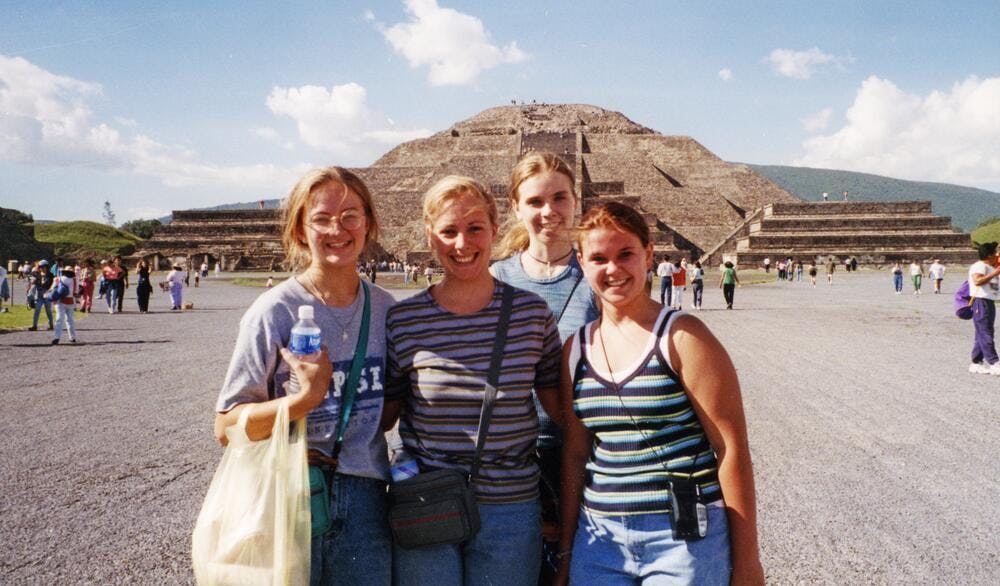

Wells, a former banker and professor of business administration, advised post-war elections in Greece and Germany and served as a delegate to the U.N. General Assembly in 1957, along with his 70-year service at the university. IUHPFL first set up shop in France, Germany and Mexico in 1962, one year after President John F. Kennedy’s establishment of the Peace Corps. By the summer of 2025, the program had served some 8,600 Hoosier high schoolers.

Language training, music programs and its School of Medicine formed perhaps the most distinctive wedge of the university’s global reputation. Beginning with Russian in the aftermath of Sputnik, IU secured a series of major government and foundation investments to support language learning. Ultimately, Bloomington would offer instruction in over 70 languages from around the world, more than any other university in the country.

In his 1980 book, “The Tongue-Tied American,” an otherwise scathing appraisal of what he labeled the “national language crisis,” Illinois Congressman (and future Senator) Paul Simon singled out Indiana as an exception both for its multi-campus Consortium for International Programs and program for high school students. On both economic and security grounds, Simon urged his fellow legislators to “start speaking with the rest of the world” and to “(develop) a generation of business leaders who understand that it is essential to have knowledge of another culture and another language.” To paraphrase the advice of one of Simon’s Japanese interlocutors: the most useful language in world trade is the language of your client.

IU, together with other higher educational institutions, provided an important bridge to the state’s economic growth. By 2013, Indiana ranked among the top 10 state exporters in 23 industries, including first in pharmaceuticals and motor vehicle bodies, third in engines and turbines and ninth in agricultural products. A bipartisan embrace of business, education and international diplomacy was signaled by the creation of IU’s School of Global and International Studies in 2012, an effort commemorated six years later in its renaming to honor Democrat Lee Hamilton and Republican Richard Lugar.

What signal, one must ask, do legislators and university leaders mean to send by these current, crushing attacks on language programs? Is Indiana’s socio-economic well-being also on an indefinite “hiatus?”

Leon Fink (he/him) is Distinguished Professor of History Emeritus at the University of Illinois at Chicago and author, most recently, of Undoing the Liberal World Order (Columbia University Press, 2022).