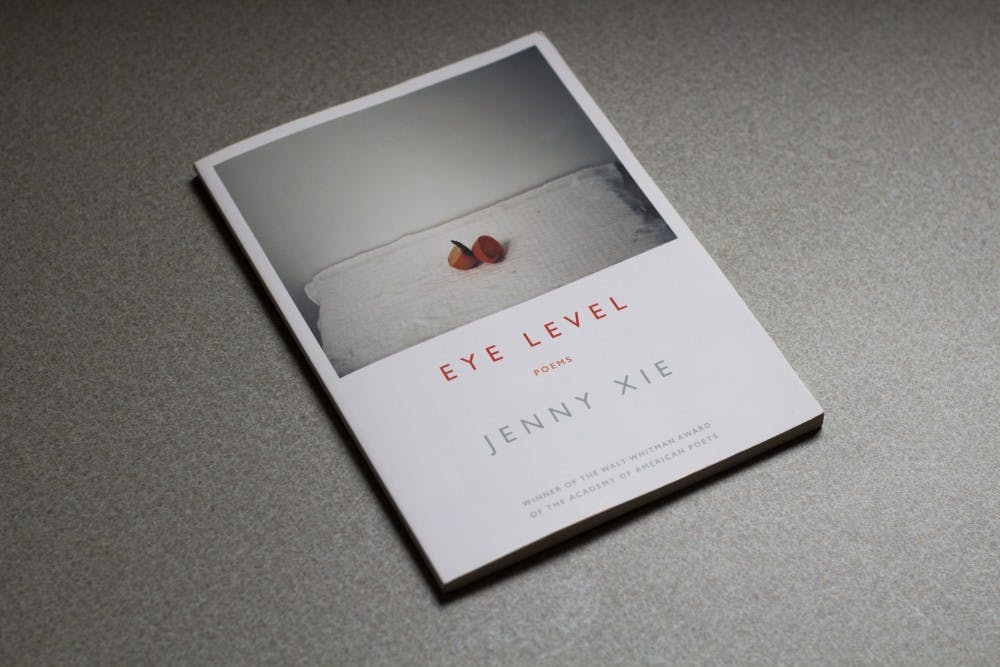

Jenny Xie's debut poetry collection, “Eye Level," is a book that looks around in transient spaces.

Born in China and raised in New Jersey, Xie is interested in the timely and topical division between here and there, the familiar and the distant and, most importantly to her, the interior and the exterior.

The collection’s first poem, “Rootless,” begins with a phrase emblematic of these divisions, set on a train between two Vietnamese towns: “Between Hanoi and Sapa there are clean slabs of rice fields and no two brick houses in a row.”

The poem ends, “At present, on this sleeper train, there’s nowhere to arrive./Me? I’m just here in my traveler’s clothes, trying on each passing town for size.”

By the time she passes into each town, she’s already stripped it off — a fleeting gaze of a place that remains unknown.

Much of the book reflects on how the familiar and the distant blur in these temporary spaces. Regardless of where in the world she travels, her poetry captures in quiet sentences what feels like well-worn solitude alongside a sense of distance from her present situation, her own perspective and sense of self.

Xie communicates this solitude through stark, unembellished presentations of the world around her. “Phnom Penh Diptych: Wet Season” and “Phnom Penh Diptych: Dry Season” carry dry descriptions of passing people and city life. Here, other humans are obscured to her, but she remains concealed just the same:

“In the kitchen, I catch myself in a pan of water, but there I am transparent./You could say moving here was a kind of hiding.”

This unfamiliarity is also found in her interactions with people. In Cambodia, the owner of a Chinese restaurant asks her to fix the English on his menu while she eats, and his daughter asks if she’s just passing through.

Xie’s unadorned lines give them weight — they are austere, like observations made in indifference, the way one experiencing an old, familiar detachment might perceive an unfamiliar world. The result is a beautiful and intelligent collection of poetry.

In this way, exterior descriptions reflect Xie’s interior — the body’s environment matches the mind.

“Corfu” reflects on landing at the tiny airport on Corfu Island, Greece. The poem describes the simple nature of the setting, but also defines the calm, minimal language the book strides on:

“One line through customs,/and the plane impossibly close to the sea./No ceremony in any of it.”

In “Invisible Relations,” people are just as much a stranger to her as she is to them, creating a sense of stranger-ness within oneself, a seclusion that soaks through the collection.

Another focus of her poetry is on the distance between the past and the present. Namely, how memories and the passage of time inhibit and affect the now.

Snapshots of her own childhood speak to just how much perspective can change between periods of one’s lifetime, in poems such as the engrossing “Zuihitsu” and “Lunar Year, 1988.”

Xie avoids dipping into melancholy or whimsical nostalgia. She retains a muted and charged way of viewing the past — a place of longing and struggle, within herself and within her family’s financial and cultural schisms.

In “Chinatown Diptych,” she speaks of adaptation to the United States as “what’s given against what’s stolen” from herself and her cultural roots.

Especially in our contemporary moment, Xie's poetry makes this foreignness less foreign — combating xenophobia and racism, the reader can empathize with her struggles and thereby understand new social perspectives.

Regardless of topic, Xie is interested in how the distance between here and there — past and present, of seeing without being seen — can be the same as the distance between interior and exterior.

No matter what Xie writes about, her poetry offers beautiful, gray-hued portraits of an outward looking, inward-focused perspective, all without flourishes or decoration. This distilled style never ceases to be evocative in language or motif, and unbridled humanity swells throughout the entire collection.

Some of her prose poetry, such as “Bildungsroman” offers in cool, stunning lines how such conflicts of interior and exterior carry monumental implications:

“We felt time segmenting like lichens, a shade of ourselves quickening. In front of our eyes, the wind whipped its subjects forth in tune with some strange choreography. You could walk into a name for yourself. You could walk into a fear of being robbed of your life.”