I’ve been waiting for the emergence of queer heroes since I was a little fifth grader swooning about the rippling depictions of gods and heroes in my copy of “D’Auliare’s Book of Greek Myths.”

I think, though, that my search for the queer hero (and my pending thesis topic) unfolded when I saw Pixar’s “Brave.”

I left the theater feeling disappointed. Pixar has only ever challenged their audience with socially-conscious storylines and daringly dark material for the likes of kids. But “Brave” was mere tokenism in its seemingly “feminist” backing.

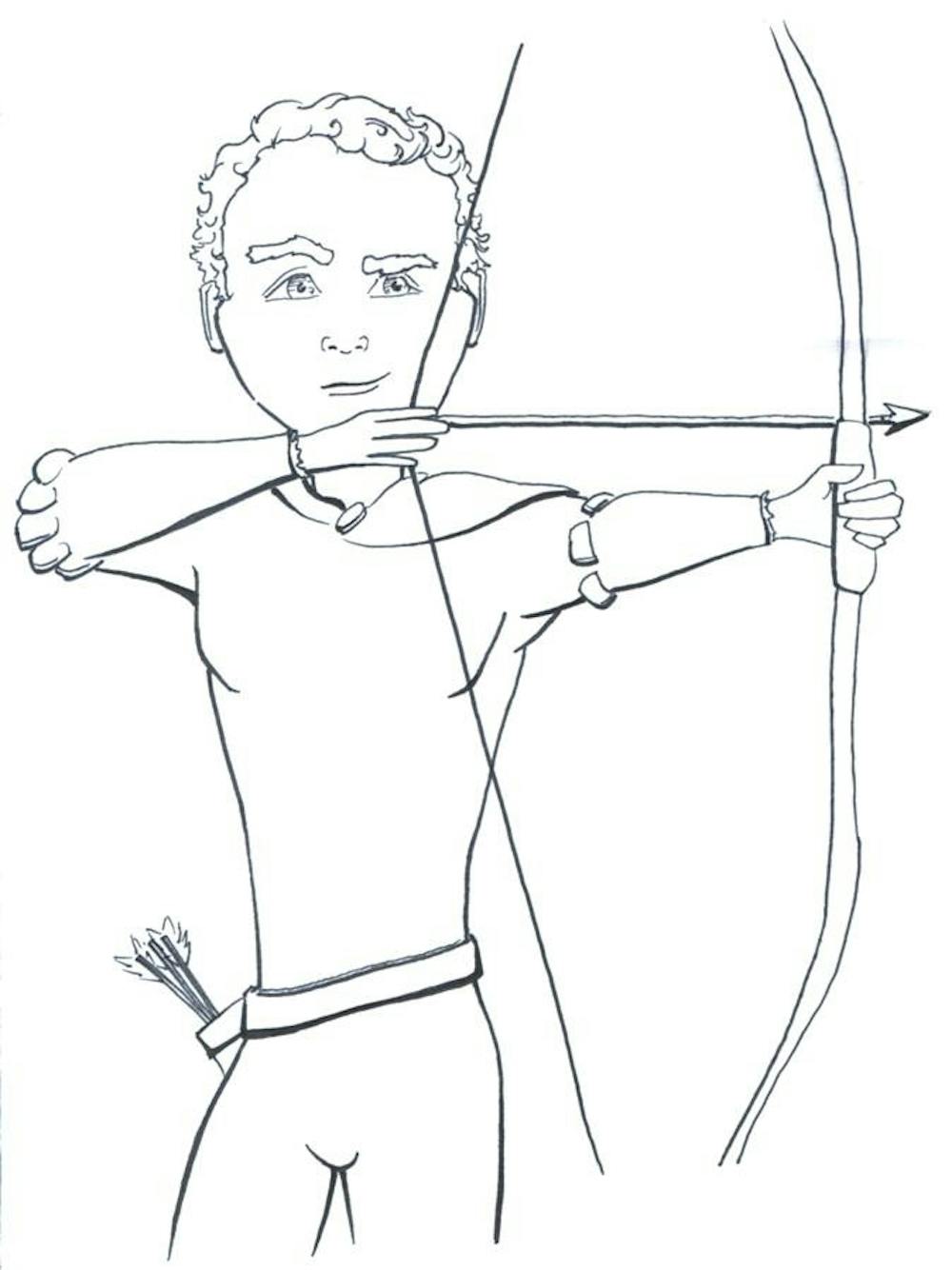

Giving the female protagonist, Merida, a weapon — not to mention, a frail, long-range weapon — is an underdeveloped idea, and hardly forward-thinking. We’ve seen girls with weapons before, and thank goodness, feminine brutality has already manifested itself and been normalized.

And then I thought to myself, “‘Brave’ would have been much more progressive had they replaced Merida with a redheaded, bow-wielding, sword-slinging gay man.”

This would vastly start to reconstruct the girly, foppish stereotype found in most movie representations, i.e. the “Glee”-type. Movies are foreclosing on the gay guy’s potentially dynamic character with the constant reappearance of stereotypes — the Gay Best Friend, the Sassy Maestro, the Fashion Naysayer, the Socially Repressed.

In a world where gay oppression has been overbearingly natural, our media representations often stick to that plot — “Brokeback Mountain” or otherwise. What that story accomplishes, though, is that gay people are heroes in real life, and should be in fiction, too.

I’m all for reversing the hackneyed image, but it’s important that in the construction of this homosexual masculinity — ”homomasculinity” — we accurately assess a multiplicity of gay perspectives.

You could hardly walk up to someone and say, “describe a straight person” and expect a straight answer. But if you asked, “describe a gay person,” they could probably sketch out the stereotype. This is phenomenon deluded and ill-conceived.

Gay people have a culture, divided into many, many subcultures. We differentiate, and many of us would shatter the gay mold existing now.

So, if “Brave’s” Merida were actually, let’s say, Murtagh the gay killing machine, what does that add? Aside from breaking the pattern, we finally have a gay character that can defend himself, instead of needing best friends, parents or judicial systems to run to their cause.

The beauty of a narrative outside of reality is that, in a fantasy terrain, gay oppression doesn’t have to dominate the narrative. Game of Thrones, while their gay warriors are hugely progressive in their exposure, unfortunately still adhere to the secrecy and insecurities of gay subjugation.

Gay heroism that focuses on action and adventure — the physical, narrative incident of the protagonist — helps the gay character demonstrate their struggles in actuality, rather than politically or internally. The weapon gives agency directly to the gay character, not indirectly via some gesture for equality. The queer hero can defend himself, thank you.

Not only that, but queer heroism allows us to reconsider what it is, exactly, that makes a hero. Bravery and physicality have always been a part of the equation, but if we spun the archetypal hero with this new gay sensibility, the depth of a character could also involve a facet of self-acceptance. The ability to conquer ourselves, per se, would heighten the value of a hero who also conquers others. Our quest is not the liberation of identity but the liberation of self.

Let the gay guy pick up the sword.

— ftirado@indiana.edu

We need more queer heroes, part 2

Get stories like this in your inbox

Subscribe