Jordan Goldklang spent much of his childhood mesmerizing friends and family with tricks and optical illusions. In middle school, he’d grab a deck of cards or a fistful of coins and spellbind his classmates whenever he got the chance.

Teachers begged him to stop, saying the magic was disruptive. They confiscated his cards, told him to put the coins away, and even called his parents, pleading for help, but nothing worked. School was the ultimate testing ground for his tricks, he says, a place where he could both perfect his art and connect with his peers.

When he arrived at IU four years ago, he thought he’d have to give up his beloved hobby to study “something serious.” But in an ironic twist, the 21-year-old senior is now majoring in magic, taking a range of classes to both hone his performance skills and develop an understanding of the psychology behind the age-old craft.

“It’s been kind of a dream come true,” he says. “For so long, I was told not to do magic in school, and now I’m going to school for magic.”

He’s one of a growing number of students breaking away from prescriptive majors and choosing to design their own degrees through IU’s Individualized Major Program. The program, part of the College of Arts and Sciences, lets students put together a customized mix of classes – usually spread throughout different schools and departments across campus – that match their interests.

Some degrees defy convention. One student majors in comedy writing, while others pursue offbeat topics such as violin making or concert-and-festival production. A few years ago, a student created a major in beer. He studied entrepreneurial brewing in hopes of eventually opening his own microbrewery.

Those zany degrees attract attention, but they’re just as tough as any other on campus, Ray Hedin, the director of the IMP says. Students need to meet all of the requirements of COAS’ bachelor of arts degree, plus complete at least a 25-page final paper or a creative project prior to graduation.

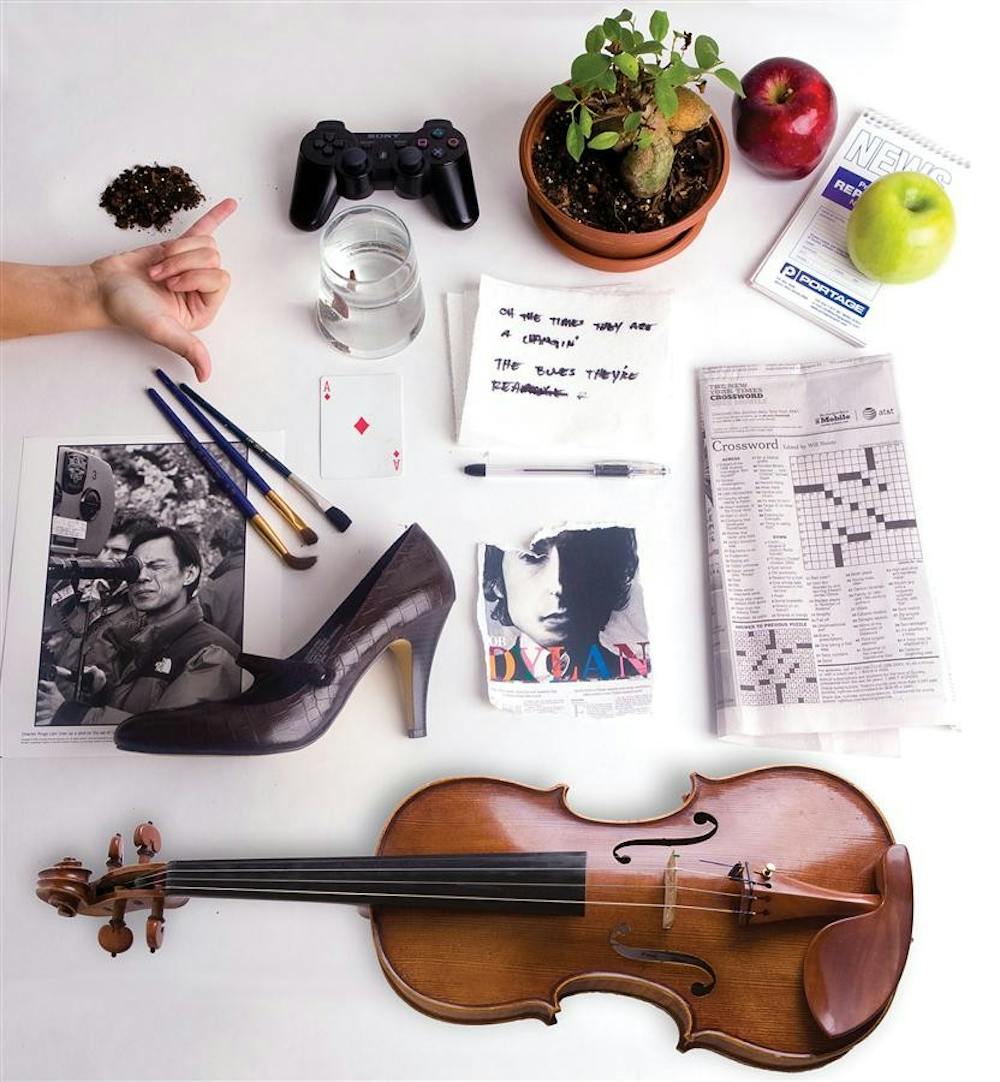

In Goldklang’s major, he’s not learning how to shuffle cards or make a rabbit disappear into a hat. Instead, he’s enrolled in anthropology, theater, business, and psychology courses designed to deepen his understanding of magic. In anthropology, he’s studying witchcraft and alternative beliefs. In theater, he’s learning how to refine his stage presence and perform in a front of a live audience. At the Kelley School of Business, classes such as “L201: The Legal Environment of Business” will teach him how to ink contracts with comedy clubs, while psychology allows him to get inside the minds of his audience.

Rob Goldstone, a cognitive psychology professor and one of Goldklang’s advisers, says all those courses make sense. Take psychology, for example. In a common trick, a magician will place a penny on a table and cover it with a cup. He’ll then lift up the cup to show that it’s been replaced by a pen cap. Simple enough. But in another version, the magician might raise the cup and show that the penny had been replaced with a bent coin.

“In both cases, you’re doing trivial substitution illusions,” Goldstone says. “But if you’re substituting a coin for a bent coin, people are thinking, ‘Oh my gosh, he magically bent that coin, that’s amazing.’ It’s relevant for the magician to know what’s going to impress the audience more.”

IU’s Individualized Major Program developed in the late 1960s as students questioned authority and fought to take charge of their own education. For years, it maintained a low profile, enrolling about 30 students at any given time. Over time, though, the program increased its stature and pumped out notable alums, including New York Times crossword master Will Shortz, who graduated with a degree in enigmatology, or puzzle-making, in 1974.

Though no organization tracks the number of individualized major programs in existence today, studies show that more and more students are choosing degrees that combine courses from multiple subject areas – something called interdisciplinary studies. In 1991, 17,000 students graduated with interdisciplinary degrees nationwide, according to figures from the National Center for Educational Statistics. By 2006, that figure spiked nearly 80 percent, when more than 32,000 people received such degrees.

William H. Newell, executive director of the Association for Integrative Studies at Miami University in Ohio, says it’s understandable that students would want to choose or design a major that covers more than one subject area. “It’s really blossoming,” Newell says. “The nature of the world that we’re living in these days is so complex that you really need training in how to deal with complex issues.”

Even so, some suggest that our culture could be behind the push to develop one-of-a-kind47 majors. In today’s society, where students are used to customizing everything from their drink order at Starbucks to their TV shows with TiVo, a one-size-fits-all approach to education seems outdated. “It’s the idea of putting your own structure on the world,” Goldstone says. “I think that’s a great part of the attraction, of being able to impose your own world view on intellectual disciplines.”

But when students tell professors what they want to study, instead of the other way around, does that disrupt a fundamental balance of power? Not necessarily, Goldstone says. “From a professor’s perspective, if you get students who care enough about their education to take control of it themselves, usually the reaction is, ‘more power to you, go for it,’” he says. “The professors think, ‘Great this is just what we want.’”

Still, so-called designer-degree programs are hardly the norm. On a campus of more than 40,000 students, only about 150 are enrolled in the IMP at one time. Most enter the program as sophomores or juniors after trying out a conventional major and realizing it wasn’t actually what they wanted.

Junior Nikki Ashkin started as a business major but decided she wanted to pursue an environmental science major with a certificate from the Liberal Arts and Management Program. When that wasn’t possible, she designed her own major – “sustainable management” – that incorporates both management and the environment. Her goal is to someday work for her father’s “green” cleaning consultancy or become a university professor. The Individualized Major Program, she says, let’s her sample all kinds of relevant courses. “It’s really neat, because each semester, it’s not like I’m only taking business classes or I’m only taking science classes,” she says. “With my program, I can kind of take a whole range of classes and as long as I can prove that it relates back to my focus and as long as I fulfill all of the requirements for COAS, it’s acceptable.”

The program doesn’t only help students: It also acts as an incubator for degrees that later become full-fledged majors within the University. Women’s studies – later renamed gender studies – started in the IMP, as did cognitive science and musical theater. In that sense, the IMP serves as a “cultural register” or an early trend spotter, Hedin says. “We send signals to the University as to where interest is developing, which is very useful to the institution,” he says.

The current growth area is “problem-based majors” that address issues of sustainability, alternative energy, globalization, and the environment.

Junior Julia Greenwald came up with a major that combines her interests in politics and fair trade. The major, “Nonprofit Retail Management with Concentration in Fair Trade,” focuses on the principles of fair trade, poverty, and inequality. She’s taking economics classes to learn how financial systems operate in other countries, and she’s dabbling in merchandising courses, in case she one day works for a fair trade retailer or importer. She says the pay off will come with her first job.

“I just find that my generation overwhelmingly wants to do something,” she says. “I don’t know if it’s because we’re in college right now and we’re naive and we want to do something that changes the world, but I feel like we want to do something that helps the environment and doesn’t hurt the environment.”

Goldklang, the magician, sees another appeal. The program, he says, lets people pursue their interests even if they don’t have a place within most University degree programs.

“I came here to study music, but it turned out to be the perfect school to major in magic,” Goldklang says. “Here’s this passion that I have that I can’t study anywhere else.”

Sticking out

Get stories like this in your inbox

Subscribe