To whom much is given, much is required.

It’s a paraphrase of a saying from the Bible in Luke 12:48, which states, “For unto whomsoever much is given, of him shall be much required: and to whom men have committed much, of him they will ask the more.”

It was one of many sayings of the late, great George Taliaferro, a college football hall of fame inductee who helped integrate IU and the Bloomington community. Taliaferro died Oct. 8 at the age of 91.

Donna Taliaferro, one of George’s four daughters, said that saying resonates with her the most after the passing of her father.

“I found out that that’s who he was,” she said. “He gave so much. Not only to us, but to everybody that he encountered.”

***

The story of Taliaferro is not one to go unnoticed in the history books.

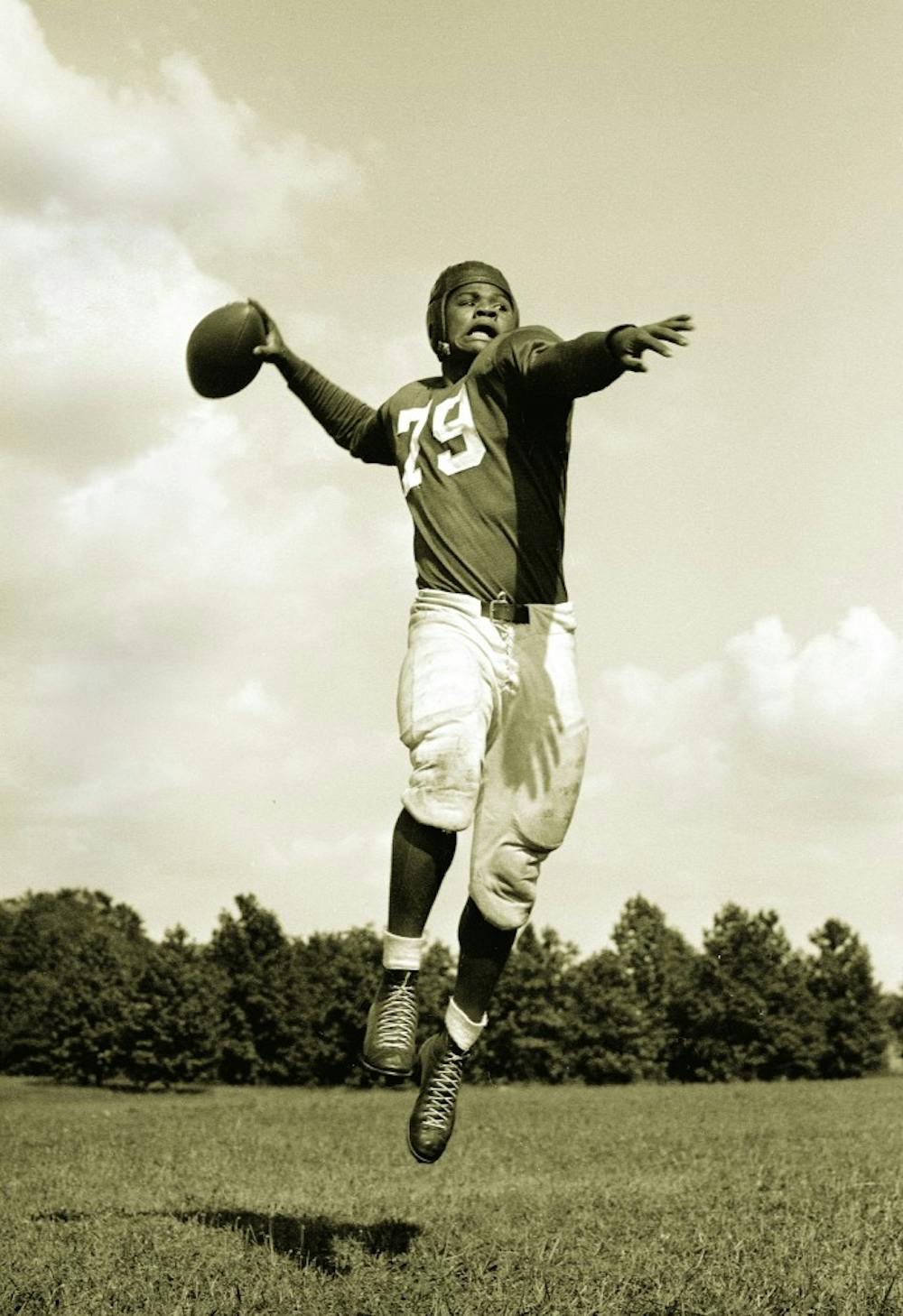

Taliaferro, a native of Gary, Indiana, came to IU in 1945 to play football, and could play just about every position. He almost never left the field. Despite his success, Taliaferro met discrimination everywhere he turned.

While playing, he was spit on, kicked when he was down and called many names.

Taliaferro ignored it and let his talent speak for itself. In 1945, sporting the number 44, he helped IU go 9-0-1, which to this day is the only undefeated team in school history.

He wasn’t alone when he was on the field, though.

Mark Deal, IU’s assistant athletic director for alumni relations, told a story about how his father, Russ, the captain of the 1945 team, would drive Taliaferro home when he would visit his wife, who lived in Gary.

People would look at Deal’s father weirdly and question why he was in the same car as a black man.

“George is my teammate, he’s my friend, and I’m taking him home,” Russ Deal replied.

Taliaferro went on to be a three-time All-American at IU before making even more history. In 1949, the Chicago Bears drafted Taliaferro, making him the first ever black player drafted into the NFL. Although he never played for the Bears, he went to the Los Angeles Dons of the All-America Football Conference to begin his professional career.

In 1950, Taliaferro began his NFL career with the New York Yanks. Throughout his career, he also played for the Dallas Texans, Baltimore Colts and Philadelphia Eagles. He continued his versatility as well in the NFL. As a running back, he ran for 2,266 yards on 498 carries with 15 rushing touchdowns; as a receiver, he had 95 receptions for 1,300 yards and 12 touchdowns; and as a quarterback, he passed for 1,633 yards and 10 touchdowns.

"We played Michigan at Ann Arbor the first game of the season in 1945," Taliaferro said in an audio clip published by the Undefeated. "When I walked outside into that stadium and saw the size of the stadium, I looked skyward and asked God, 'Why am I here?' and I said, 'They're going to catch hell. Catch me.'"

From then on he made all his opponents catch hell, and nobody stood a chance catching him. He was a trailblazer on and off the field.

When he wasn't scoring touchdowns on the football field, Taliaferro faced the struggles that many African Americans faced at this time. He couldn't live on campus. He had to live with a family in Bloomington. He couldn’t eat at restaurants. When the team traveled, he couldn’t stay with them at the same hotel.

His daughter said one of the things that were instilled in her father by his parents, Robert and Virnater, was the importance of an education and opportunity it presents. George Taliaferro took that to heart and did more than just graduate from IU.

“He wasn’t bitter, he was motivated to do something about it,” said Gary Sailes, a professor at IU who teaches about Taliaferro in his History of Sports & the African American Experience class. “There’s a difference, and that’s one of the things I really liked about George. His idea of revenge was to be successful — to break down those barriers and do it in a civil way.”

Taliaferro started breaking down that barrier with the Gables restaurant, more commonly known today as BuffaLouie’s.

IU president at the time, Herman B Wells, heard about how Taliaferro had to run home between classes to eat food because no local restaurants would feed him. The picture of IU’s football team was inside the restaurant, and Taliaferro could only look at himself in that picture from the window.

Wells called the owner at Gables, and said he and Taliaferro would be having lunch there one afternoon. The manager was hesitant with the idea, and Wells responded by saying that he would make all restaurants on South Indiana Avenue off-limits to the entire school body.

Wells and Taliaferro had lunch, and the Bloomington community was slowly being desegregated.

One Tuesday, Taliaferro bought a ticket to see a movie in the Princess Theatre, which is located near the Courthouse Square in Bloomington. His ticket was for the balcony section marked "colored."

Taliaferro went there, removed the sign and brought it home with him.

Sailes occasionally got Taliaferro to come guest speak in his classes, and he would bring the "colored" sign with him to every single one. He kept it for life.

When he had his kids, Taliaferro continued to fight discrimination with his wife Viola — the two were peas in a pod. Donna Taliaferro recalled a time in elementary school where the teacher assigned all the kids to draw a winter scene. She drew a snowman and colored it blue. The teacher, who was white, chastised her for coloring it blue.

“Snowmen are not blue. Why would you draw that?” She recalls the teacher telling her.

It left Donna in tears and she went home to tell her mom and dad. Viola, who was a teacher at the high school, came up to the school and told Donna’s teacher that if that’s how she saw the snowman, then that’s what he was. It wasn’t for her to determine what it should look like.

“I always knew I was protected,” Donna Taliaferro said of her parents’ strength to stand up for what’s right.

***

A video tribute of Taliaferro played on the two big screens inside Memorial Stadium for IU's 2018 homecoming game against Iowa on Oct. 13.

The flags were at half-staff, and after the video, a moment of silence was taken for the icon.

The Hoosiers' helmets did not have the typical IU logo or cursive Indiana writing on one of it. Instead, the helmets had the number 44.

Senior linebacker Thomas Allen, who regularly wears 44 for the Hoosiers, changed his number to 10 for this game. Senior offensive lineman Delory Baker Jr. led the team out of the tunnel, holding the coveted 44 jersey in honor of Taliaferro.

"I just wanted to not wear it for this one game just for him because he's a trailblazer," Allen said. "Everything he's done for this University and the NFL has been amazing."

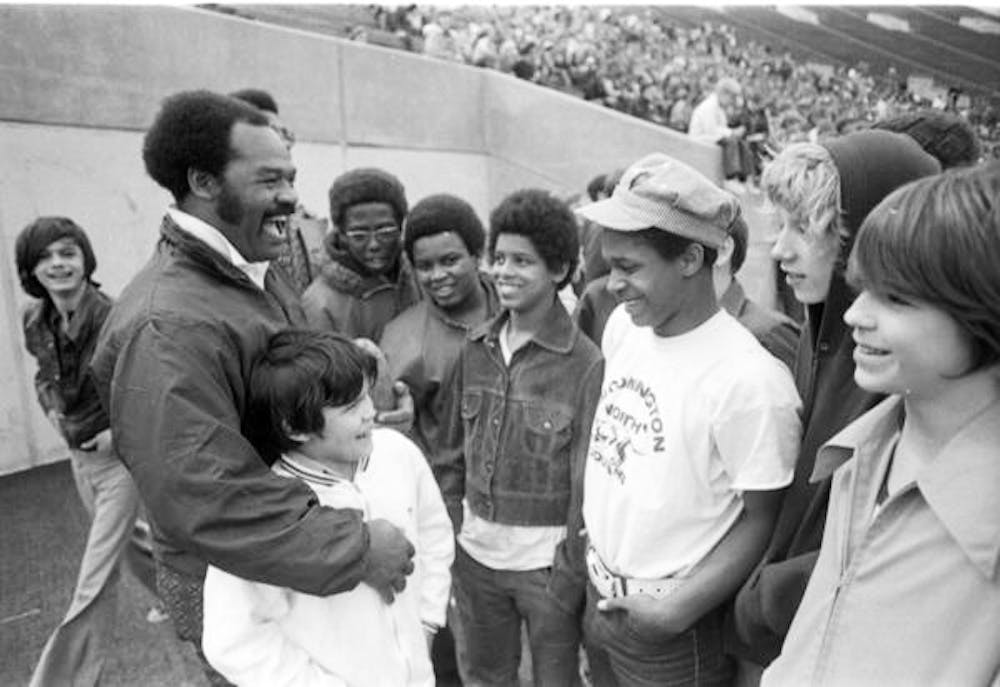

Up until his death, Taliaferro was active — abnormally active for someone in their 70's and 80's — and strived to make a difference in people's lives.

Both Deal and Sailes said Taliaferro would play golf and carry his own bags instead of taking a cart. Since Sailes is about 20 years younger, he thought he could act like Taliaferro and carry his own clubs.

“Man, did I regret it,” Sailes said. “I had a back ache, and I want you to know that was the last time I ever carried my bags.”

Deal would usually play golf with Taliaferro — something Sailes said is his biggest regret — and said that Taliaferro was very good and always hit it down the middle. But, he would stray off into the woods and search for golf balls. He would collect them and store them in his garage, where he had garbage bags filled with golf balls. He would take the golf balls to Indianapolis and donate them to underprivileged kids in the inner city to try and get them involved in the game.

“Even playing nine holes of golf with George you got an insight into the man, and how he was always thinking of somebody else,” Deal said.

Eric Love, an IU alumnus, said he was doing a historical research paper for graduate school and interviewed Taliaferro for it. George being George, he offered more than just an interview, and the two began to get lunch frequently and become close friends.

Four days after his death, Love couldn’t help but let the tears flow when recalling when he found out the news of losing an icon and an amazing friend.

Ed Schwartzman, the owner of BuffaLouie’s, said any time Taliaferro would come into his restaurant and would sit alone, students would approach him and be in a trance as Taliaferro would talk to them. Schwartzman said he’ll never forget the message Taliaferro wrote on one of the pictures of himself in the restaurant: “To Ed, all the best to ya! Mine has been a great life! – George Taliaferro.”

Taliaferro appreciated everything he had and wanted others to have great lives, too. He was constantly giving speeches to students, he worked with the Boys and Girls Club of Bloomington, he served as COTA’s Board Chairman. At IU, he was special assistant to the president of the University, the IU-Purdue University Indianapolis chancellor and the dean of the School of Social Work. The list goes on.

“I am very, very, very honored to have my name associated with making a contribution and making it in the right way,” Taliaferro said in the audio clip published by the The Undefeated.

Donna Taliaferro doesn’t just think of her father’s saying — "to whom much is given, much is required" — as a remembrance, but as a passing of the baton.

“The statement is now it’s on you,” Donna Taliaferro said. “If you feel I gave you something so great, that you hold me in this regard, it’s your turn. It’s your responsibility.”