The Holocaust happened 67 years ago. It happened across an ocean. But it happened to our professors, our grandparents, our neighbors.

For these survivors, this six-year period is still part of everyday life. It prevents them from sleeping at night, from watching horror films, from trusting others with their stories. It shaped their childhoods, their careers, their outlooks on life, and their reasons for coming to Bloomington.

But with every passing day, their stories fall further back into history.

“The longer we move away in time from the Holocaust, the more difficult it is for people to find relevance,” says Jacob Bielasiak, professor of a class on the Holocaust and politics.

It was imperative for this issue to include survivors of one of the world’s greatest tragedies — especially since they are living in our community. Our generation is the last to hear their stories firsthand. By sharing their experiences, these five survivors challenge us to keep the memory of the Holocaust alive.

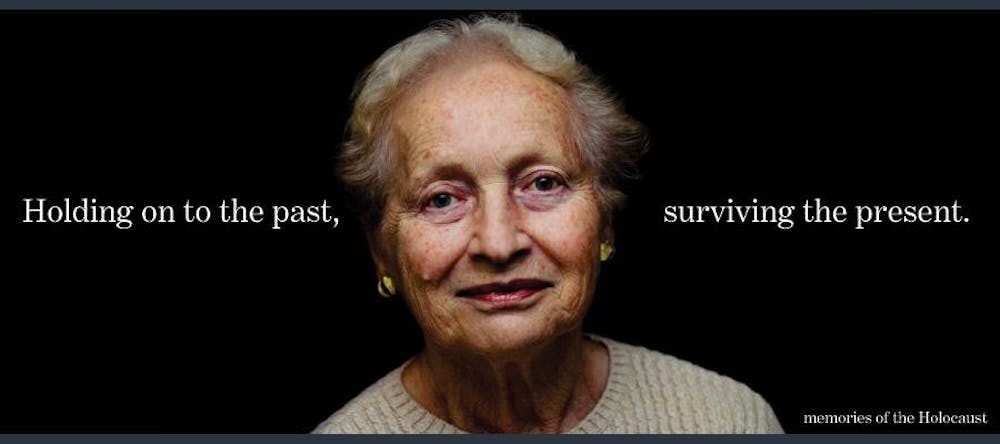

Mimi Taylor

BY JESSICA CONTRERA

Miriam “Mimi” Taylor, wife of a retired IU professor, was 3 years old when the ordinance was issued that all Jews must be moved to the ghetto of Chernivtsi.

Mimi’s father had a close friend whose sister lived in the area that later became the ghetto. The woman allowed Mimi and her parents, as well as 18 others, to stay in her apartment.

The ordinance declared that after the Jews were concentrated in the ghetto, they were to be deported to Transnistria, an area controlled by the Nazis and Romanians during the War. Transnistria was, more or less, an unorganized Romanian concentration camp for the extermination of Jews.

Her family eluded deportation through the unexpected kindness of a Romanian man — Traian Popovici, the mayor of Chernivtsi.

Popovici asked that the Jews not be deported so that the city would not come to a standstill. The dictator of Romania allowed him to give out approximately 15,000 permits, which gave a person permission to stay in Chernivtsi. Mimi says he forged about 4,000 more permits.

Mimi’s family was given one of those permits. It was enough to keep them safe and alive for most of the war — but for her grandmother, great aunt, cousin, and friends, there was no salvation.

The trauma that most affected Mimi didn’t occur until after the war.

“As I got older, I understood better,” she says. “For years, I heard about the absolutely horrible things that happened. At a very young age, I decided that if I ever had to live through another war, I would commit suicide.”

Today, Mimi preserves the memory of her family, her heritage, and her city. She has digitized all of her family’s photos and documents from the time of the war and contributes to an online forum with others who once lived in Chernivtsi.

Mimi has organized past preservation projects including rehabilitating a Jewish cemetery in Chernivtsi and installing a memorial plaque of Popovici, the mayor who saved so many Chernivtsian Jews from deportation. Currently, she’s working on having the stories of the forum’s members published.

“When I come across new information about the city or the Holocaust, I try and make it known,” Mimi says. “We should never forget our history.”

Paula*

BY ALYSSA GOLDMAN

Paula*, an 86-year-old former student and employee at IU, lived with uncertainty during her three-month detainment in Auschwitz Concentration Camp.

As a Jewish French citizen, Paula spent many of her teen years moving around from town to town hoping to avoid Nazi persecution.

In March 1944, Paula decided to go to a friend’s art studio. She was part of “The Resistance,” an underground movement that aimed to free Europe from Nazi power. Paula’s group of friends was responsible for producing anti-Nazi leaflets. She walked into the apartment without knocking and when she stepped inside, she found three French policemen pointing their guns in her direction.

Paula spent time in French and German prisons for three months before being transported to Drancy, an internment camp that was used as a “holding place” before prisoners were deported to extermination camps. On July 31, 1944, she started her three-day journey on a cattle car to Auschwitz.

“In hindsight, we gained time from March to July,” Paula says. “If we were sent to Auschwitz earlier, I might not be alive now.”

With little access to water and food, she arrived to Auschwitz dazed and confused.

The prisoners were shaved, forced to undress, and tattooed with their designated numbers. Paula was No. 16,749. Their clothes, shoes, and other belongings were taken from them and thrown into a pile. Then they had to pick from a pile of other prisoners’ clothing that had been disinfected. Paula chose a skirt, shirt, shoes, and a slip. She possessed nothing with any connection to her identity.

“I picked up a slip since there were no actual toilets, just a big box where everyone did their business, with no toilet paper,” Paula said. “Little by little the slip began to shrink, until there wasn’t a slip anymore. I just didn’t want to be dirty.”

Paula washed her hair whenever possible since lice was a threat to prisoners’ lives.

“It was a matter of luck if you didn’t catch typhus,” she said. “If you didn’t catch typhus, you had a chance of survival. If you had typhus, you died.”

In November, Paula was inspected by the camp “doctor” — the person who decided who lived and who died. The doctor looked at their frail, nude bodies and decided who would be sent to work in a Czechoslovakian factory and who would be sent to the gas chambers.

Paula was told she would be transported to Czechoslovakia, but she was commanded to shower prior to departure. She had no choice but to comply, not knowing if gas or water would emit from the sprinklers. Luckily for Paula, it was the latter.

Today, Paula’s mind races at night: What could she have done differently? How could she have been a better person? It doesn’t help that people have trivialized her experience. She has been asked if it was as horrific as its portrayal and believes society no longer cares. By revealing her name, Paula thought readers would think she was complaining or could react with anti-Semitism. To younger people, Paula assumes the story of the Holocaust is just that, a story.

Peter Jacobi

BY ALYSSA GOLDMAN

Being born to a Jewish mother and an outspoken father didn’t bode well for School of Journalism Professor Emeritus Peter Jacobi in 1930s Berlin.

In the beginning stages of Nazi rule, Peter’s caretaker stole several items from the family’s household. His father reported her to the authorities. The police spoke with her and suggested his father drop the charges because she claimed to have heard anti-Nazi speech used at the dinner table. If he pressed charges, his father would suffer more than the caretaker.

“Musicals like ‘Cabaret’ and the ‘Sound of Music’ aren’t far off in terms of a society in which people changed,” Peter says. “Former friends would become enemies, and you had to watch yourself — watch how you acted and watch what you said.”

Life as a “half-Jew” was difficult and confusing. Although Peter’s parents wanted him to attend a private Jewish day school to escape Nazi propaganda, the German government wouldn’t allow him to attend since he was not quite Jewish enough. However, he was still discriminated against at school.

“I had some teachers who were old German disciplinarians that beat up everybody,” Peter says. “But then I had some Nazi teachers who were selective of who they bothered.”

Although his father was not Jewish, his deli was graffitied with “Jude” and Stars of David. Eventually, he had to close his shop.

Life in Germany was becoming too much to bear for the Jacobis. In 1936, his father went to the U.S. for what he called a “business trip” to visit Peter’s uncle, an accountant for some prominent figures in the music industry. These important individuals wrote affidavits for the family, and they fled from Berlin to the U.S. in 1938.

“Fortunately,” Peter says, “we never had to find out what could have been.”

Zhanna Arshanskaya

BY ALYSSA GOLDMAN

Zhanna Arshanskaya, an 84-year-old former professor at the Jacobs School of Music, fled the death march at Drobitsky Yar, a ravine near Kharkov, Ukraine. Her father had a pocket watch buried in his winter jacket and used it to bribe one of the Ukrainian guards. Before 14-year-old Zhanna went into the world to fend for herself, her father placed his heavy winter jacket onto her shoulders and said, “I don’t care what you do — just live!”

In the distance, Zhanna saw some older women watching the procession. She tried to blend in with the other onlookers, and pretended to be caught within the tangled, ragged barbed wires.

Somehow Zhanna’s younger sister, Frina, also escaped the death march. They spent five years in hiding and depended on the kindness of righteous gentiles, or “angels,” as she calls them.

Their survival tactic: performing.

As students of Kharkov’s music conservatory, they were taught by renowned pianists and performed throughout the Ukraine. Their success in the music world made hiding even more difficult. Zhanna and Frina took on the identity of orphan daughters of an on-duty officer in the Russian army and a mother killed in the bombing of Kharkov.

Their musical talents were later discovered and they were hired as performers in a theater troupe. But they had to perform for German soldiers — the people they were so desperately trying to escape. And because Zhanna was the main talent and received the best pay and the most praise, she became the target of much animosity.

The troupe’s ballet dancers claimed the sisters were Jewish. This rumor made its way to the Nazi commandants — twice. The commandants questioned a woman whose son was once their classmate. On two separate occasions, she told the Nazis she knew their parents and was certain the sisters weren’t Jewish.

“It was a miracle of some proportion that angels were willing to sacrifice themselves,” Zhanna says. “She chanced her and her son’s life. Just imagining the courage it takes to do this is mind boggling.”

Conrad Weiner

BY ALYSSA GOLDMAN

Conrad Weiner, a 74-year-old ’66 IU graduate, had an encounter with death before he even reached double digits.

For Conrad, the Holocaust is a vague memory pieced together by other family members and his own research. At age 3 and a half, he, his uncle, and his mother had to leave their home in Bucovina, a part of Romania at the time, and were forced to march to the Ukraine’s Budi Labor Camp.On the side of the road, his family thought they saw branches covered with snow and mud. What they actually saw were dead bodies.

Dying during the two-week march was not only plausible — it was likely. His uncle had military experience, so his family would arrange sleeping shifts to ensure that no one would die of the freezing temperatures.

It was in the labor camp that Conrad fell extremely ill. Unable to hold any food down, fellow prisoners told his mother to let him die in peace.

“Fortunately, she didn’t listen to them,” he says with a laugh. At the risk of her own life, she would climb up the cherry trees to retrieve stems and twigs and from that would make tea. His mother’s concoctions and her bravery ultimately helped him regain strength.

It wasn’t until 2007 that Conrad decided to share his story with the world. While substituting for a 10th grade class, a student asked him if he ever met Hitler. Conrad responded, “Europe is a large continent, and Hitler and I traveled in different circles.” When Conrad explained that he spent three years in a concentration camp, the student asked, “What were you concentrating on?”

In that moment, Conrad decided he must share his story with the younger generations. When he publicly spoke of his experience for the first time, he was upset with his son for bringing his granddaughters to the presentation. His 10-year-old granddaughter, Alex, later wrote the poem, “The Survivor.”

One of its stanzas read, “His memories are filled with hardships. But his heart was filled with hope. He hoped to find light, and reader: There was light on the way.

... He knew it with all his heart.”

Jacob Bielasiak

BY JESSICA CONTRERA

The Holocaust not only impacts those who lived it; it affects those who grew up around its stories, its legacy, and the pain and suffering it caused.

Political science professor Jacob Bielasiak’s parents never directly talked to him about the Holocaust, but they didn’t have to.

“It penetrated everything, like osmosis,” Jacob says. “As a child of a survivor, you learn very quickly that certain subjects are taboo. You learn you have a responsibility to make your parents feel comfortable.”

Jacob’s parents survived multiple concentration camps, including Auschwitz. His father lost his first wife and daughter. His mother lost every member of her family.

It wasn’t until the 1980s, after he had been teaching at IU for nearly 10 years, that Jacob realized he had a calling to teach about the Holocaust. He teaches both Y352: The Holocaust and Politics and Y348: The Politics of Genocide.

“I do talk about my personal experience from time to time so that it doesn’t become just reading about some abstract things,” Jacob says. “It’s difficult, but I consider it my own personal memorial to my parents and to those who suffered and survived.”

Jacob says he believes there is a large gap between where we are today and what went on during the Holocaust.

“We can read about it and see documentaries and movies, and I can tell personal stories about it, but ultimately, that gap remains,” Jacob says.

That’s his biggest challenge as a professor: closing that disparity, even if only by a small amount, so that the Holocaust becomes real to our generation.

Holding on to the past, surviving the present

Holocaust surviviors now

Get stories like this in your inbox

Subscribe