Clouds were gathering overhead as I drove home on I-74. I was headed into a spring storm, the kind that comes on quickly on the interstate, and wanted to try to reach him again before it hit.

I pressed the call button and drummed my fingers on the wheel. I waited as the blue seconds ticked by on my car’s display, breathing through the rings until it finally went to voicemail.

I ended the call before I could leave another desperate message. If he was using again, he wouldn’t listen anyway.

The year I was five, right after Mom and I left, he sent me a homemade card every month. He printed them from his computer, with messages like “Happy Spring to the Pookie Girl!”

When I was older, he’d call every few weeks. I had to gently remind him that if he tried on Fridays, I’d be out with my friends.

Since I’d started at IU last year, we’d spoken less and less. Now it had been six weeks, the longest time I could remember. I hadn’t called because I was afraid of what I’d hear.

When he finally called back a few minutes later, he was slurring his words. From halfway across the country, I could hear he’d hit rock bottom.

Fat raindrops hit my windshield.

***

My stepmother told me three years ago that my dad had a prescription drug addiction. It had been going on for years, she said, with little change until now.

“Lately, he’s been mixing it with whiskey.”

I became obsessed with imagining what the pills actually looked like.

I imagined the chalky horse pills I took after an outpatient surgery in ninth grade. I remembered rounder, smaller ones the oral surgeon gave me in return for my wisdom teeth a few years earlier. I only took two, because they made me sick.

After I found out about his addiction, I realized I hadn’t thrown those pills away. It was my first question for him.

“Did you steal the Vicodin left over from my surgery?”

He paused, looked me straight in the eye.

“Yes,” he said. “Yes I did.”

Finding out that someone you love has a drug addiction can taint every single good memory of them. When I remember the time he showed up to my eighth grade basketball camp wearing tube socks and sandals, I wonder if he couldn’t find the right shoes because he was stoned. Every mistake now seems like a symptom.

It leads me to ask questions I don’t want answered. How many times did he drive me somewhere high? How much of my childhood does he remember?

***

The first time I recognized that he was using, it hit me like a slap in the face.

In the darkness of my grandmother’s kitchen, I found his 6-foot 6-inch frame crouched in front of the refrigerator, rocking back on his heels as he gripped the freezer door handle.

“What are you doing?”

“I’m looking for the elusive ginger ale.”

He was slurring. I looked behind him to the counter, where the scattered remains of a package of bagels I’d bought that morning laid next to empty containers of bread, raisins and crackers. He’d eaten his way through every snack in the house.

I stood frozen in the doorframe as he staggered to the couch with the last can of Seagram’s. He stretched out on the couch, the last bagel balanced on his heaving chest. Within seconds he was snoring. I crept to the recliner next to the couch. For ten minutes I watched him wake up to eat and drift off again, like some enormous bear fattening up for winter.

I went back to the guest bed and curled into a comma on the comforter. I stuffed a pillow into my mouth so my grandmother wouldn’t hear. As I cried, I let the waves of anger and anguish and disgust crash over me until I was spent.

***

I hate my father most of the time. I hate him because he doesn’t act like I think an adult should, and because he didn’t stop using when my mother left him fifteen years ago. I hate that I grew up thinking he was sober, and feeling guilty that he wasn’t a bigger part of my life.

When that hate is more than I can stand, I force myself to remember the good times we had. My favorite times were the ones Dad called “dawn patrols.”

We started when I was 14. On those days, I’d wake up around six and cross the hall to make sure he was awake. We’d pull on our suits and sandals and just go.

On our way to Virginia Beach, we’d sip coffee and talk about wind direction and whether or not the waves would be choppy. By seven we’d be at the jetty. We never took time to test the water before jumping in.

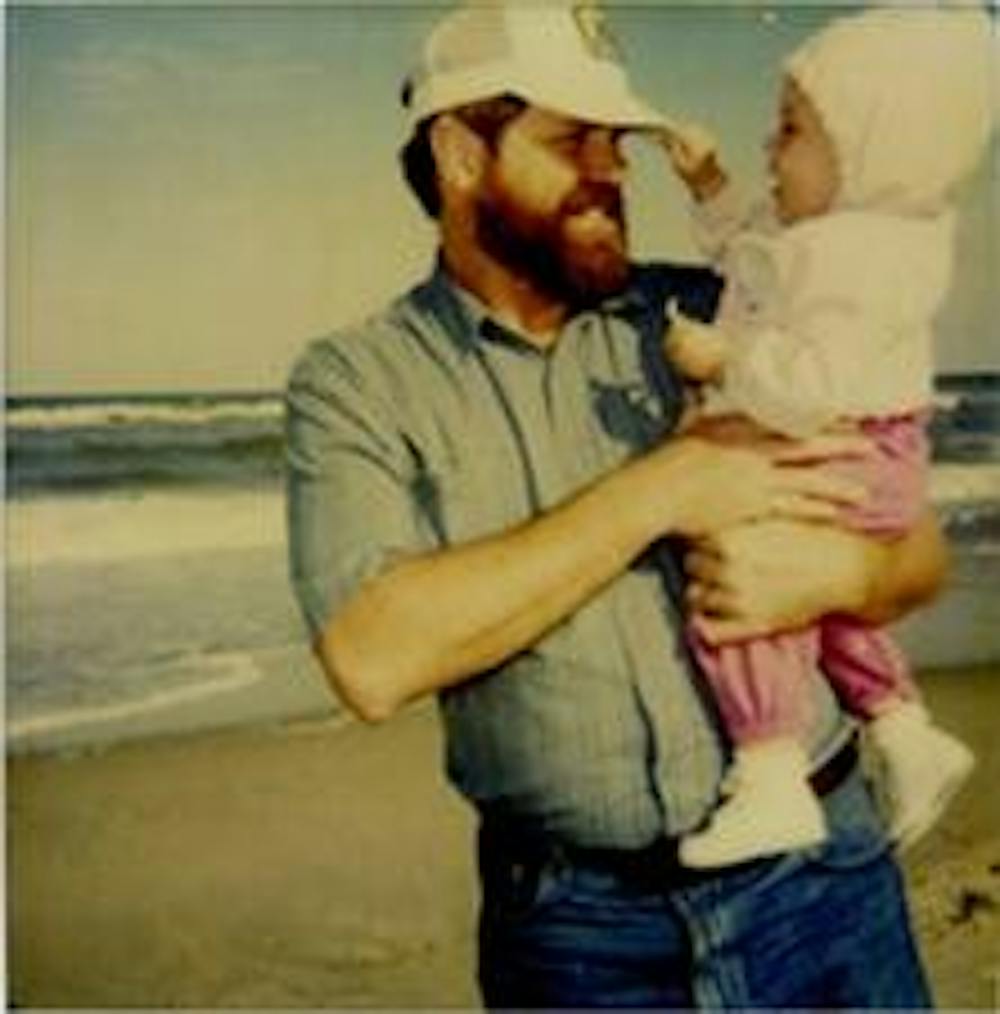

He taught me to swim right after I learned to walk. He put me on a boogie board and shoved me into a wave not long after that. I remember the jolt as I tumbled toward shore.

It was careless of him to send me out that way. Still, he taught me to understand the water. Love and respect for the ocean are things I’ll carry the rest of my life.

It’s the same for him. Despite his boney knees and too-big feet, my dad and his yellow Morey Boogie still cut gracefully down the face of every wave he chose to ride. He defied the laws of physics. He knew how to handle the ocean.

For most of my life, I watched him carry a heavy sadness. I always knew he missed my mother. I knew he regretted the years of silence he shared with his own father. And I knew he regretted giving up his dreams—of medical school, of basketball fame, and of making it as a songwriter in Nashville.

My dad used drugs to lift the burden of that regret. He also used the ocean.

From him I learned that you shouldn’t carry your worries into the sea. I saw it in the way his frown lines disappeared every time his toes touched the water.

On dawn patrols, we understood each other. We’d linger just beyond the breakers, hands on our boards, looking out for the next set and talking about our lives.

As I got older, we discussed my college search and campus tours and boyfriends.

He told me that it was fine to make mistakes every once in a while.

In the water, I respected him. He became the father I wanted him to be.

Now it is hard for me to look back on those times and not feel it was a lie. I imagine all his memories of me are hazy. After all that time, maybe he doesn’t really know me at all.

After I found out he was using, we only went to the ocean a few times. I could barely stand talking to him, because I finally recognized how much of his memory, his wit, and his quirkiness—everything that made him worth talking to—had been stolen by the drugs.

But in the water, I couldn’t ignore him. As sick as he was, he had clarity there.

The beaches where we’d been the closest became the only places I could stand to look him in the eye.

***

“How are you, Dad?”

“I’m doing great, sweetie pie. They told me I can go home. So I booked a flight for Wednesday. I’m going to stay in a motel in Huntington Beach tonight. I’ve never been in the Pacific!”

He had started calling again as soon as the rehab center gave him back his phone near the end of August. He’d continued to call me nearly every day for weeks afterward, even after rehab was finished.

I still couldn’t get used to his crisper voice, or the way he didn’t constantly ask me to repeat my last sentence. I knew this meant he was doing better.

I didn’t ask him what he’d do when he got home because I didn’t want to know. If I kept thinking he had the future figured out, I could go on imagining he’d be fine.

When he first called to tell me he was checking into rehab, I was angry. I had practiced pushing him out of my life for three years, and I didn’t know where to place a version of my father that deserved my time.

The daily calls gave me time to practice fitting him back into my life. At the same time, I didn’t want more than a daily call. If I added him back in too much and he slipped, I was fairly sure I’d never be able to forgive him. Most of all, I was scared of carrying that hatred in my heart forever.

I knew that we couldn’t go back to what we were before. I couldn’t forget the things I’d learned about him or the times I’d found him stoned.

His phone calls, letters, even his gifts had a different weight now. They felt hollow.

But I know he is finally working to become whole. I know on some level that he is doing it for me. So I try to figure out how things could work between us.

It helps to picture him happy. So I imagine him at Huntington Beach. He pauses to look at the Pacific for the first time, then bounds out with his board.

The frown lines disappear from his forehead. He stands among the waves, without the weight of sadness, waiting for the next set to roll in.