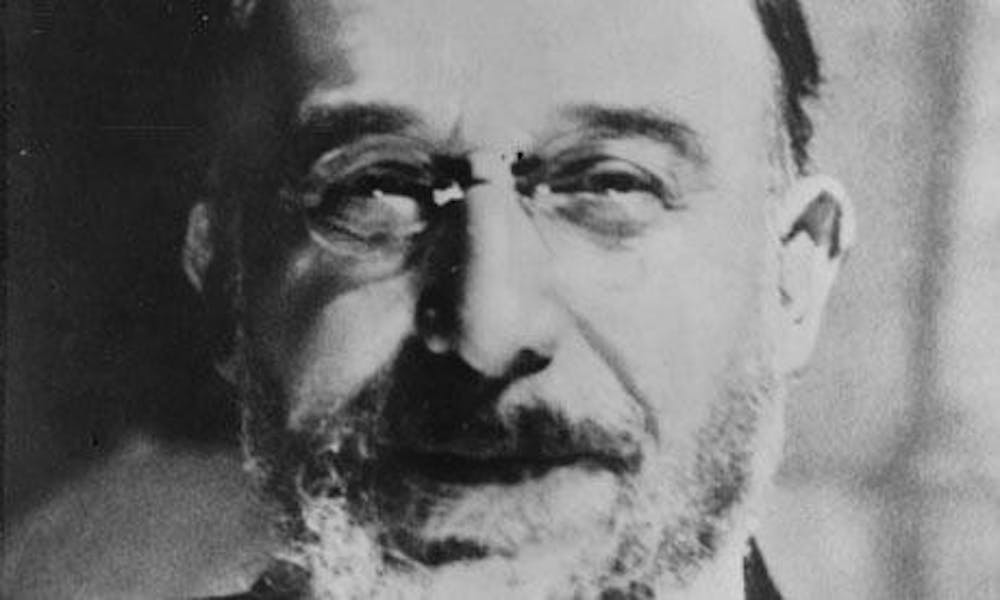

Musical paradigms have been shifting for as long as there has been music, but perhaps no single figure earned the distinction of being truly avant-garde before Erik Satie.

Born in Honfleur, France, in 1866 and a crucial figure in Montmartre’s pre-WWI “Banquet Years,” Satie stared down the classical music of his era and saw superfluous frills and pretension staring back.

So, he started cutting.

What resulted was the immediate precursor to Dada, neoclassicism and minimalism, and the very early roots of post-rock (ironically, 50 years before the dawn of rock) and ambient music.

The beautiful “So Long, Lonesome” from Explosions in the Sky’s 2007 opus “All of a Sudden I Miss Everyone” owes far more to Satie’s “Gnossiennes” suite than to any rock song, and Aphex Twin mastermind Richard David James cites the French composer as one of the biggest influences on his nightmarish electronic ambiance.

Satie’s influence today resonates in a way that is arguably more important than that of even Mozart and Beethoven. Where Mozart gave music a then-unparalleled technical flair and Beethoven brought in the full range of human emotion in a more profound way than anyone who came before him, Satie made it acceptable (albeit not immediately) to tear everything down and start over when it becomes necessary to do so.

His patently gorgeous but often challenging piano compositions spiral through scales with a feel that occasionally recalls the early works of Bach, but they have an undeniably modern twist, and listening to his masterpiece “Gymnopedies” is as fresh and exciting in 2011 as it must have been when he wrote the first part in 1888.

Notwithstanding the excellent modern artists who openly cite Satie as an influence — the aforementioned Explosions in the Sky and Aphex Twin, Frank Zappa, Gary Numan and Brian Eno, among others — the composer has indirectly been responsible for most of what sounds radical and new, especially in genres that lean on atmosphere and minimalism.

This summer, I spent a weekend in Paris and stayed in Montmartre, Erik Satie’s old stomping grounds. On a nondescript side street, nestled between overpriced wine bars and kitschy cafés near the Sacré Coeur basilica, you can see Satie’s last Paris apartment. It has ostensibly been transformed into a museum, if a series of 30-word blurbs on sketchy travel websites are to be believed, but there’s no apparent evidence of that apart from a tiny placard above the door that reads “Erik Satie — Compositeur de Musique a vécu dans cette maison de 1890 á 1898.”

Inquisitive soul that I am, I decided to defy the gendarmes and go into the apartment building to have a look around. In the lobby there were eight mailboxes with names on them. None of them said “Museé-Placard d’Erik Satie” as they should have. They just belonged to people’s homes. The most important French composer of the late 19th and early 20th centuries had apparently had the museum which was created in his honor rented out to some random Parisian.

I climbed the stairs and no evidence of any museum was up there, either. I left the apartment feeling a bit dejected, took one last look at the placard and walked back to the Metro stop.

Then it hit me that I shouldn’t feel bad at all. Satie’s apartment is just like his music. Its importance is subtly nodded to today, but it’s been built around and renovated and dug up and recontextualized. And given his approach to composition, it’s easy to imagine that Satie would be furious if things had gone any other way.

Music, to him, was not about lingering on the past or holding the old greats in reverence. It was about the march of time and the constant demand for progress. He’d likely be flattered that current musicians cite him as an influence, but more impressed yet that they’ve taken up his mantle and moved it in a number of completely disparate directions.

So, while it’s disappointing as a student of cultural history that there’s apparently no shrine to Satie’s greatness in a prominent, touristy part of Paris, it makes perfect sense. In death, as in life, his disdain for reverence is refreshing.

Erik Satie and the art of leaving the past

Get stories like this in your inbox

Subscribe