Editor's note: All opinions, columns and letters reflect the views of the individual writer and not necessarily those of the IDS or its staffers.

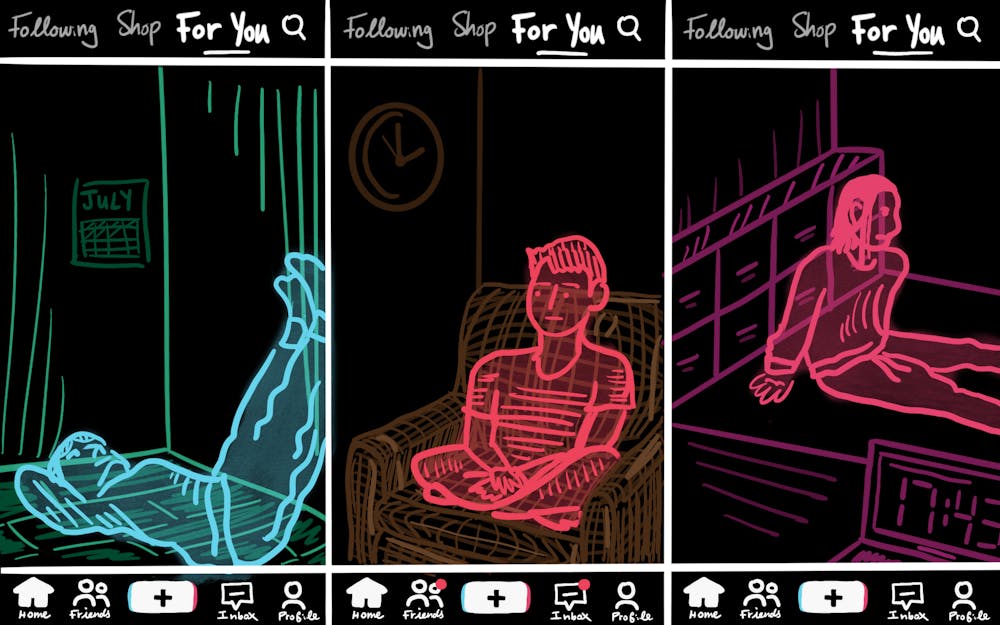

#focus. #productivity. #habitstacking. A very productive guy — and you can tell he’s productive because it’s in his username — sits in a chair recording a timelapse of himself stewing in boredom “for one hour to fix my attention span.” #dopaminedetox. If this TikTok came up on your For You page, you might scoff and wonder sarcastically how it took this long for Generation Z to discover meditation or scroll away for your next dopamine hit, like one commenter who wrote, “I couldn’t even make it through watching you do this for one minute.”

This self-deprecatory humor, characteristic of Gen Z, rings self-aware, and it’s this consciousness that defines the popularity of this trend. To some extent, we’re all aware of the guilt and passive hypnotism that sit alongside us while we scroll. Worse, doomscrolling preys on our emotions, facilitating the mean world syndrome, or the perception that the world is more dangerous than it statistically is due to heavy exposure to violent media content.

Either way, after an hour glued to the couch, you blink, look up disorientedly and feel bad — whether from wasting time or consuming depressing news. It’s this negative feeling to which people participating in the trend — challenging themselves to do nothing for long periods of time — are reacting.

The trend represents a desperate attempt to reclaim control over their minds from social media brain rot and itchy thumbs, thus “fixing” their attention spans by forcing themselves to be — and, more importantly, stay — bored.

What these video creators are picking up about short-form videos like Instagram Reels or TikToks is that scrolling unintentionally forms a habit or a vicious reward cycle. The never-ending flux of short-form video feeds lend themselves well to hijacking the brain’s dopamine system, which supplies dopamine with each quick hit of entertainment and rewards each swipe of the thumb and every half-finished video.

This habit then trains your brain to expect fast dopamine hits and makes steady, focused effort feel harder. Unsurprisingly, research has shown frequent TikTok users “scored lower in attention, inhibitory control, and working memory, the skills needed for reading, studying, and problem-solving.”

The “raw-dogging boredom” trend seems like an admirable goal, yet it can also come across as performative, especially because the idea of posting a recording on TikTok of you inherently avoiding TikTok is reminiscent of French political theorist Guy Debord’s 1967 Situationist — a cultural movement that sought to overthrow capitalism by revolutionizing the realm of everyday life — and his remarkably Marxist book The Society of the Spectacle.

In the first chapter, Debord argues when “life is presented as an immense accumulation of spectacles,” which he defines as images “detached from every aspect of life” by modern conditions, “everything that was directly lived has receded into a representation.”

Taken in the context at hand, it’s easy to transpose his ideas onto TikTok. The For You page is an “immense accumulation of spectacles,” and this trend reduces an honest wish to fight a society of spectacle from something “directly lived” into a contradictory caricature of the original idea.

Others have pointed out this futility in the boredom trend, like psychologist Dr. Danckert who told NYT writer Alexander Nazaryan it’s a “misguided approach,” and “you don’t have to do nothing.” Courting boredom is driven neither by a search for mindfulness and peace like meditation nor for reflection, introspection and emotional regulation like journaling; it’s forcing yourself into discomfort rather than “listening well to what boredom is actually telling you, which is to find something meaningful to do,” he said to Kristen French for Nautilus.

In fact, if you really want to improve your attention span, you should train it like you do your biceps instead of ineffectually forcing change in one, long, painful sitting. In the same way you train your muscles in sets, exercise your brain.

Clinical psychologist Stacey Nye says to take “active breaks,” no “passive scrolling,” to focus on only one physical or mental activity for 30 minutes: take a walk, craft with a friend, read a chapter, cook dinner.

It’s a good sign for our generation we’re collectively taking issue with the deleterious psychological effects of increasingly prevalent social media use, but this solution, unfortunately, misunderstands the actual problem at hand. This “rawdogging boredom” trend reveals how powerless we feel. Instead of turning toward the phone — or the “ever-producing change machine,” as cognitive neuroscientist Cindy Lustig calls it — to fix the problems it creates, turn away; turn into yourself for reflection; turn toward each other for connection.

Odessa Lyon (she/her) is a senior studying biology and English, pursuing a minor in European studies.