A tool developed by IU professors is on the market and foreseeing developments in gene therapy, environmental science and more.

One month into its commercial launch, the Xevo Charge Detection Mass Spectrometer developed by Megadalton Solutions holds promise in redefining the limitations of measurement science, according to Waters Corporation, owner of the technological assets and intellectual property rights of Megadalton Solutions.

The Xevo CDMS is an enhanced iteration of a charge detection mass spectrometer, an instrument that determines the mass of individual ions — atoms or groups of atoms with electrical charges.

Molecules accumulate charges through ionization techniques like electrospray, which uses electric energy to cause an imbalance in the number of protons and electrons in a molecule. Ionization is an essential process for analyzing a molecule’s composition through mass spectrometry.

Charge detection mass spectrometers find mass by simultaneously measuring the mass-to-charge ratio and the charge of singular ions.

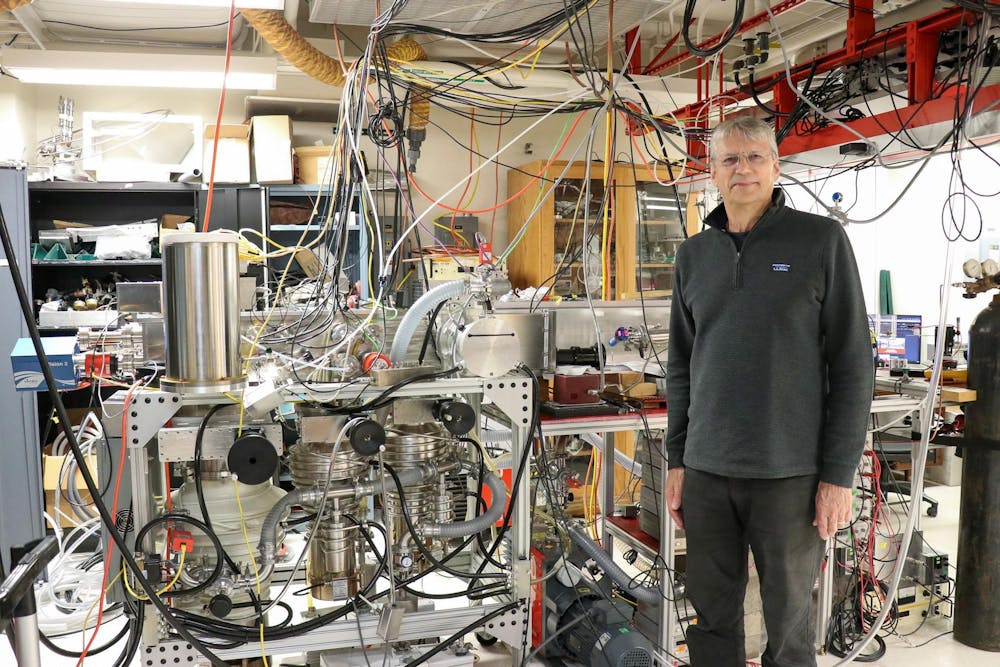

Martin F. Jarrold, distinguished professor of chemistry at IU and CEO of Megadalton Solutions, developed the Xevo CDMS that launched in fall 2025.

The Xevo CDMS uses a detection cylinder that is induced with a charge from each ion that passes through it. This cylinder is embedded within an electrostatic linear ion trap, which keeps ions intact as electric fields cause them to oscillate in the cylinder.

An amplifier connected to the cylinder then outputs a signal that when analyzed, indicates the induced charge and the ion’s oscillation frequency — how often an ion moves back and forth in the cylinder.

“From the oscillation frequency, you can get the mass-to-charge ratio, and from the amplitude of the signal, you can get the charge,” Jarrold said. “You multiply them together, and you get the mass of the ion.”

Graphically, this is visualized as molecular ion peaks on a two-dimensional plane. The position of a peak on the horizontal axis indicates an ion’s mass-to-charge ratio, while the vertical axis describes the abundance of ions at a certain mass-to-charge ratio.

This technology opens new doors for scientists in determining the composition of large, complex molecules, which was previously inconceivable with traditional mass spectrometers, Jarrold said.

Traditional mass spectrometry is limited to measuring the mass-to-charge ratio of a group of ions. Its inability to measure the exact charge of such a group of ions leads to less precise calculations for molecular mass. This is especially prevalent in complex molecules, which have a single true mass but take on multiple charge states during electrospray ionization.

Furthermore, the XEVO CDMS can measure as little as 10 microliters of the sample under study and has a resolving power of about 300; higher resolving powers allow for clearer distinction between ions with similar mass-to-charge ratios, which are visualized as narrower molecular ion peaks. Jarrold said future modifications plan for the resolving power to reach about 300,000.

He also said the ability to determine molecular mass at a level of unprecedented precision will have applications in a variety of research fields.

The Waters Corporation focused on the industry of in vivo gene therapy — a treatment for genetic disease where edited genetic material is delivered into a patient’s target cells through a viral vector, such as adeno-associated virus.

Viruses like AAV have protein shells named capsids, which are modified to become harmless carriers for therapeutic genes. These viruses infect the cells of patients with genetic disorders. Ideally, the inserted genes are expressed in the cell as a functional protein product that corrects genetic disorders or supplements genetic abnormalities.

A limitation to AAV therapy is that the insertion of therapeutic genes into capsids is not guaranteed, leading to inconsistently filled capsids and empty ones.

With charge detection mass spectrometry, researchers can better identify capsids containing genetic therapy, distinguished professor of chemistry David Clemmer said.

“The proper genome has a mass and the capsid has a mass,” Clemmer said. “And when you add them together, you get a peak at a specific mass for the proper genome inside the proper capsid.”

Clemmer, who is also the COO of Megadalton Solutions, explained that the demand for Xevo CDMS came from companies who were trying to determine which capsids contained the therapy and whether those genes could be appropriately expressed within patients.

Aside from gene therapy, both Jarrold and Clemmer predicted that charge detection mass spectrometry will have countless impacts on science.

“There's many applications for a technology that can measure masses from a million mass units up to a billion mass units,” Jarrold said. “There are issues in environmental science, to do with microplastics and things like that, that this technology could be used to detect, but it's not really been exploited in this direction yet.”

When evaluating the applications of CDMS, its accessibility is also a consideration.

“I've never been sure that this business model of building a better mass spectrometer and then charging a million dollars for it every couple of years, is a model that will continue,” Clemmer said. “A number of groups have worked on making them smaller and more affordable, but they still are very expensive.”

Manufacturing a CDMS can be as complex as it is costly and operating it requires close attention to detail.

For Jarrold, a significant challenge in building the Xevo CDMS was reducing electrical noise, unwanted interferences in electrical signals that can disturb the device’s measurements.

Jarrold said IU’s extensive instrumentation workshops were key to minimizing the electrical noise.

“The electronic shop was sort of our secret weapon in terms of developing the amplifiers that we used in the CDMS,” Jarrold said.

Still, Clemmer said he believes the commercialization of the Xevo CDMS has made the instrument more available to the scientific community. Its compact nature may also contribute to making charge detection mass spectrometry feasible for smaller research facilities and university students.

“A commercial instrument, of course, an undergraduate can use, because that's a walk-up instrument, and they can learn the theory behind it, but they don't have to keep every wire connected to every place with every voltage,” Clemmer explained.

While it is too early to determine the market success of the Xevo CDMS, Megadalton Solutions maintains a positive outlook on its adoption in current scientific fields and the discoveries it can enable.

Jarrold, who will be retiring from IU this year, envisions a continuation of his work through the Martin and Caroline Jarrold Fellowship in Measurement Science, a scholarship for graduate students at the Department of Chemistry.

“I think this is just primed for discovery,” Clemmer said. “It's like having a new dimension, a new color. And for a painting, if you had a completely new color, I think people will start painting with that color everywhere, and I think that's what's going to happen.”