Wes Anderson has always been fascinated by dysfunctional families. He’s come back to the subject again and again — most profoundly, perhaps, in his early triumph “The Royal Tenenbaums” — and “The Phoenician Scheme,” the director’s 12th and most recent feature-length picture, might be his most elaborate take on the subject.

The film could be most accurately compared to “Tenenbaums” in its precise focus on one family unit, but it also contains all the usual trappings of his later-period output. It’s an espionage tale set in the mid-20th century in a faraway country in the eastern Mediterranean. It’s set against the backdrop of a political struggle, which repeatedly rears its head into the main narrative. Anderson asks questions about religion and muses on all the philosophical uncertainties of life that come with it.

Unfortunately, what we’re left with is a film which never justifies its convolution and seems to believe it’s something much deeper than it actually is.

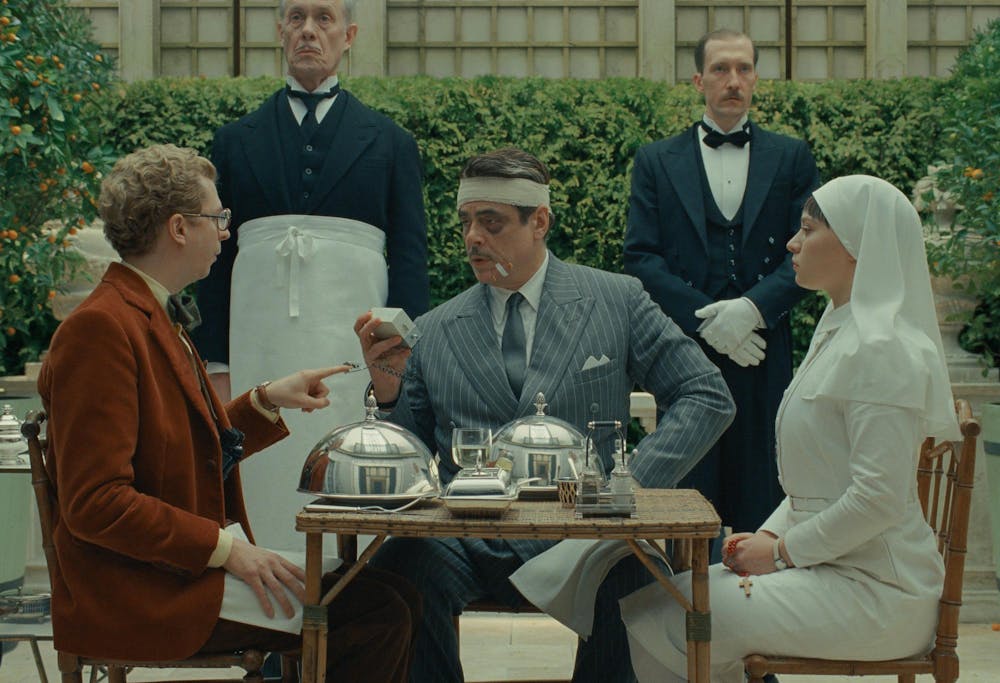

The plot follows Zsa-Zsa Korda (Benicio del Toro), a wealthy and infamous arms dealer with a penchant for surviving a slew of assassination attempts. After a harrowing plane crash, he attempts to reconnect with his estranged daughter Liesl (Mia Threapleton), who became a nun after Korda sent her to a convent after her mother’s mysterious death. She wants answers to the mystery, and he wants her to be his sole heir.

Korda’s attempts to meet and deal with investors for a plan to completely overhaul the economy of Phoenicia with slave labor drive the narrative. His estranged brother, Nubar (Benedict Cumberbatch), is both one of those investors and the man whom Korda believes killed Liesl’s mother — even though everyone else believes it was Korda himself. Throughout the film, he involves himself, to varying degrees, with communist revolutionaries, monarchical royalty, foreign spies and the angelic residents of an afterlife that may or may not be real.

Anderson’s plots are something akin to a Rube Goldberg machine, circuitous displays of whimsical complexity that ultimately harbor some very specific, grounded topics. But Anderson’s film seems much more delighted simply to wallow in the aesthetics of these topics than to actually say anything meaningful about them. Mid-century guerrilla freedom fighters sermonizing about class struggle, or Liesl debating Catholic doctrine with her father, are fanciful images, but it’s always unclear what Anderson thinks about them or whether he thinks anything at all.

In Anderson’s directorial philosophy, style comes before everything, to the point where his name has become a byword for a particular sort of quirky, twee aesthetic that’s only become more and more extravagant as he’s gotten older. Many of his recent movies, which have increasingly taken place across the Atlantic Ocean, owe a significant debt to the French New Wave, but it’s hard to argue that Anderson has taken anything from the movement besides its stylistic proclivities. A scene like the famous nine-minute tracking shot of a traffic jam in Jean-Luc Godard’s 1967 film “Weekend” might seem especially Andersonian by today’s standards, but there’s little doubt about the sort of revolutionary social and political points Godard was making when he achieved it.

This isn’t to say I have any beef with Anderson’s style per se — if his films are anything, they’re completely earnest, and his obsession with things like symmetry and a pale color spectrum are just part of who he is. It’s just the fact his style has become something closer to a gilded veneer that is the issue. It’s true that “The Phoenician Scheme” is a fun enough movie, and I don’t necessarily dislike it, but I just wish it were less dull as I began to scratch away the surface.

I was hoping for something much better, considering how tremendous “Asteroid City,” Anderson’s last film, was. With that movie, Anderson seemed to be saying, “I’m at the point in my career where my style needs to be increasingly metatextual and self-aware both to continue to evolve and to say anything at all.” Unfortunately, with “The Phoenician Scheme,” it seems this plan has totally screeched to a halt.

I’m so glad that inventive filmmakers like him still exist, and anything he creates is going to have more heart and soul than your average Hollywood assembly line slop. But, for an artist so intent on grabbing our attention, perhaps the worst thing about “The Phoenician Scheme” is the fact it’s so forgettable.