Growing up in India, I was always fascinated by the sciences, partly because my parents worked in those disciplines and partly because I thought they answered or at least attempted to answer the most fundamental questions of the universe.

Nine-year-old Advait was naive —I distinctly remember having a conversation with my parents about the future of my education and what came of that conversation was clear: I would eventually study abroad. I did not understand what studying abroad actually entailed at the time and still do not fully grasp it now. Now that the study abroad dream of mine has been realized, I find myself confused.

Immigration from the Indian subcontinent to the United States can be traced back to the late 1800s to early 1900s. The early immigrants had great sway over the cultural perceptions of Indians in the U.S., but I believe the biggest change happened with the 1990 reforms that introduced a new temporary visa category for highly skilled workers.

In the U.S., the rise of the information technology field, the decline in the number of undergraduates with a degree in key sciences and a shortage of staff in highly technical industries like software development created the perfect environment for graduates of top Indian technical schools like the Indian Institute of Technology to immigrate for a life with higher wages and better living conditions overall.

From a socioeconomic lens, 1991 saw the fall of the Soviet Union, a major Indian ally, and multiple economic adversities in India, like the fall in foreign reserves and balance of payment issues that led to the liberalization, privatization and globalization policy reforms in India. These reforms opened the Indian economy and the labour force to the world.

These reforms came at a time of technological revolution around the world. Naturally, many individuals were incentivized to get an education in the field. Becoming an engineer was one of the few opportunities that poor to lower-middle-class individuals with access to education had toward upward social mobility. It remains one of the most prevalent opportunities to climb the socioeconomic ladder today.

The idea of becoming an engineer then transcended from just having a financial incentive to a form of societal expectation among Indians. This career path has become an aspiration for many young Indians who are socialized into following a definitive path from the day they are born.

I was incentivized to study STEM subjects in school. Studying the sciences is viewed as intellectual and meticulous whereas the arts or humanities are typically frowned upon in Indian culture. I would be cautious to not make a general claim about the perceptions of these fields but rather think of them as societal expectations that I was subjected to.

Many Indian immigrants carry this view with them to the U.S., thus mimicking the societal conditions of Indian communities where technical and medical jobs are not simply respected for their economic advantages but are valued due to the societal status and respect they derive.

The higher incomes people earn from these jobs does contribute toward the formation of such status, but it also represents the qualities of hard work and analytical thinking in society. This history of mass migration and its focus on technical jobs leads to the formation of a perceived identity for Indian students, and subsequently, stereotypes.

Stereotypes, however positive they may be, are detrimental to individuals who are pressured with this perceived identity. Not living up to common expectations can lead to a feeling of exclusion — a feeling that I experience regularly as an international student at IU.

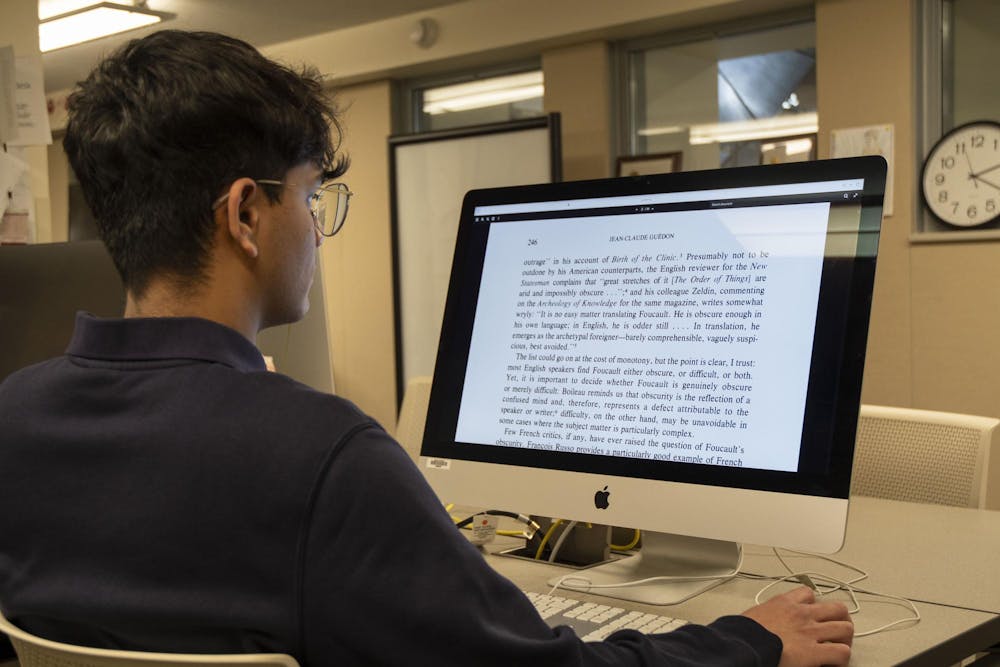

My fascination with the sciences led me to study economics and sociology, a path unconventional to the history and expectations that follow me here. I cannot ignore that baggage, but I do wish to change the perception people have of what Indian people “should” be. I cannot change the perceived identity itself but rather create awareness about how Indians are more than mere IT professionals who only have our career path to contribute.

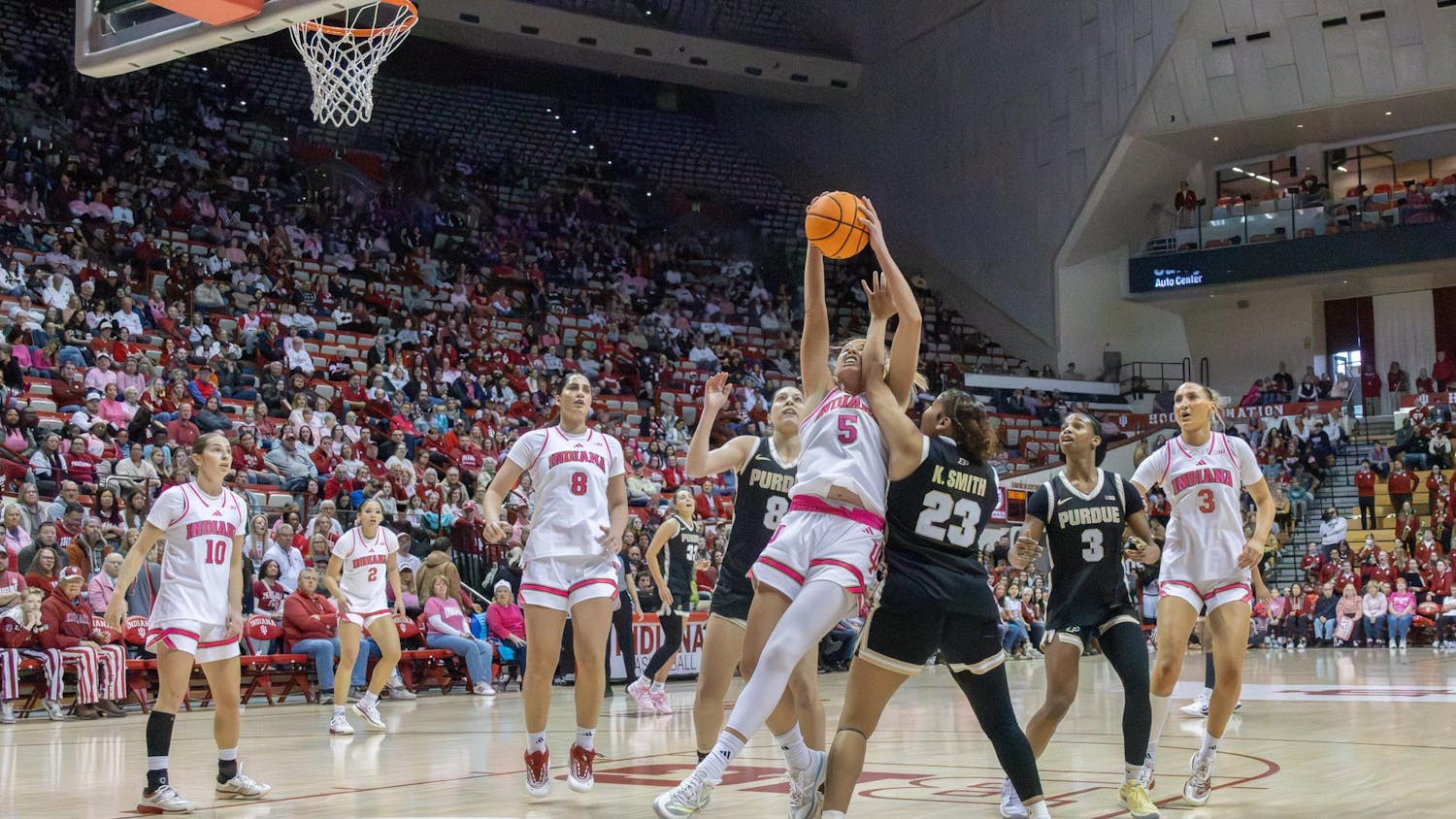

Our culture has a lot more to offer — we are artists, activists and athletes. I wish to see heightened visibility for Indians in various fields, even those not related to STEM and their excellence there. Indian authors like Arundhati Roy and Amitav Ghosh and artists like Anish Kapoor are a good place to start when exploring Indians in more artistic fields.

Let us foster a world where we celebrate Indian talent that extends beyond the confines of perceived expectations and certain disciplines. As for me, I am not an engineer.

Advait Save (he/they) is a freshman studying economics and sociology.