The sports world is often thought to be where logical expectations are suspended and the unbelievable can happen. Hell, it’s March. This is the month when the entire country is looking for an upset, a shake-up, the status-quo to topple down.

In line with that tradition, I’m challenging sports fans this March to think about the long-used ill-considered language used when talking about women’s sports.

There has long been a disparity between how organizations and fans refer to men’s and women’s sports. We need to take a deep look at why we say the things we do when referring to women in sports.

Oftentimes, when a sport is being played, most people automatically assume it is men who are playing that sport.

It makes sense that we need a way to denote when men’s and women’s teams are playing sports. However, our labels should remain consistent. It should be “men’s basketball” and “women’s basketball,” not “basketball” and “women’s basketball.”

This kind of language is called gender marking, IU sports media professor Lauren Smith said. Since male sports are considered the norm, she said they lack that label, so the gender of those playing is assumed. When thinking of soccer, basketball or hockey, people assume that the game will be played by men, unless it is noted that women are competing instead.

“That sets that tone for the male event being the standard,” Smith said. “Then the female event gets marked as the other — the less standard, the less important, the less interesting.”

What does not make sense is when teams think adding the “lady” suffix before their mascot brings any value. Some have history, like the Lady Vols at the University of Tennessee, but dozens of NCAA programs throughout all three divisions still insist on adding this unnecessary and dividing title to their women’s sports teams.

Once upon a time, I played sports. I was a lady gael and a lady falcon, and for some reason called a lady blazer once. Yes, our mascot was a business casual jacket. Yes, I went to an all-girls school. Why someone felt the need to assign a gender to a piece of semi-formal clothing is beyond me.

That’s beside the point, but it’s gratuitous language. We would never add “gentlemen” before a men’s team’s mascot, so why do we do it for the women?

Smith said this particular language falls back onto old ideas that women should not play sports, that they should be ladies first and athletes second. She said those who share this view expect women to look appropriate and express their femininity while on the field and court.

This is also seen in media coverage. Smith said women are spoken about in terms of traditional femininity, like being mothers or dating their significant others, instead of their academic achievements and skill.

Now, all this language is commonplace. It’s how the TV guides classify teams, the names college athletic programs call themselves and how the commentators consequently refer to them on broadcasts. It makes sense that fans would follow suit.

But we don’t have to perpetuate it.

Last year, players on the women’s basketball teams playing at the NCAA Tournament took to social media to express their disappointment and disapproval of the organizing body’s very apparent equity issues.

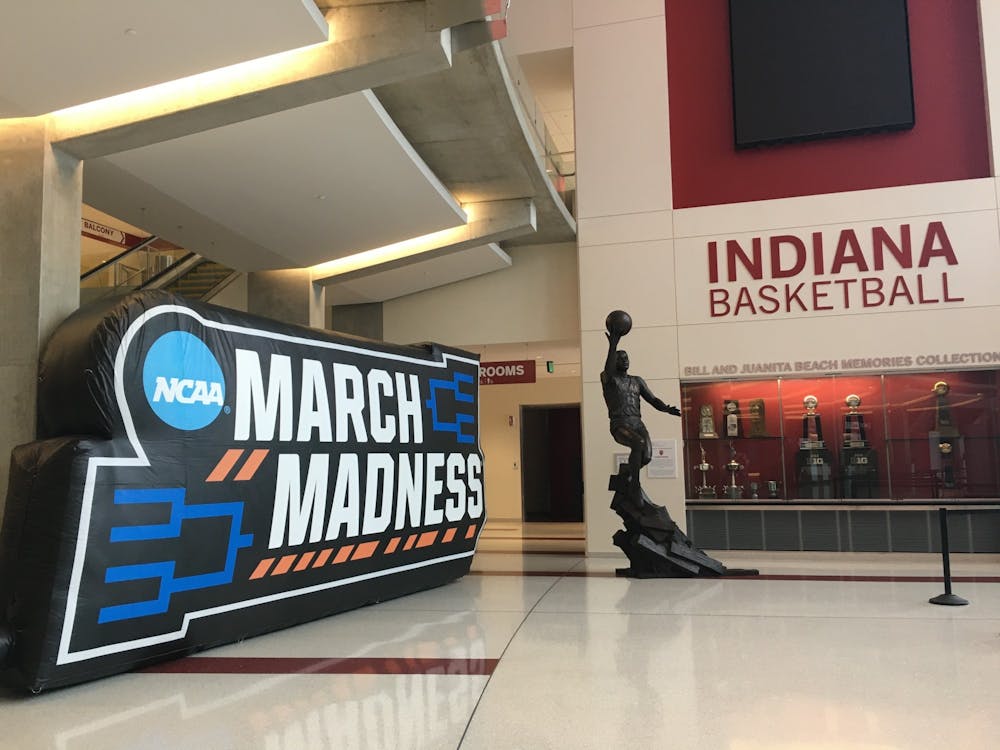

Those athletes inspired change, and they started a much needed conversation. In response, they received higher quality meals, an adequate weight room and their tournament this year is marketed under the March Madness branding for the first time.

Fans and athletes have a platform to make their voices heard on social media. They can call out the TV stations and leagues overlooking women’s sports. They can demand why a high profile women’s basketball game is hidden behind a paywall. They can exhibit that a loyal and passionate fanbase and market exists.

However, the problem of inequity won’t be entirely solved by fans tweaking how they speak about women’s sports. According to a 2021 Purdue study, ESPN’s SportsCenter program in 2019 included coverage of women’s sports about 5.4% of the time and only 3.5% when not taking the 2019 Women’s World Cup into account. The report concluded that women’s sports receive the same amount of news coverage as they did 30 years ago.

Contrary to the deceiving lack of national broadcast attention even the top women’s sports teams receive, this is not because no one is watching.

All women’s sports are on the rise. The National Women’s Soccer League experienced a 500% increase in viewership in 2020. The Women’s College World Series averaged 1.84 million viewers for the 2021 edition of the three-game series. The second game of that series had higher viewership than an NHL playoff game on the same day.

Amending our language is not going to catapult us to the top of this mountain of a problem. But it’s a start.