From 1960 to her death in 2004, Lucia Berlin wrote more than 70 short stories, published them in journals and magazines, but never received critical renown. Publisher Farrar, Straus Giroux released her first posthumous collection, “A Manual for Cleaning Women,” in 2015, 11 years after Berlin died from cancer.

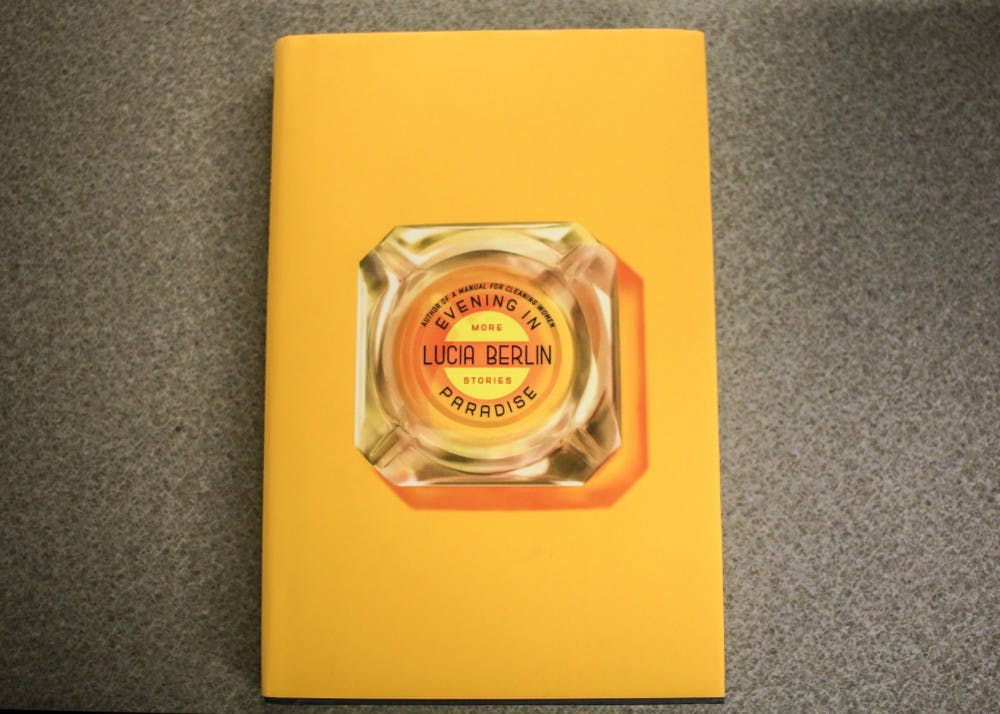

Twenty-two of her stories come together in her second posthumous collection “Evening in Paradise,” published Nov. 6.

“Evening in Paradise” explores people dealing with abusive and unsustainable relationships. Berlin writes from a broad range of distant, lonely locales, such as Chile, Mexico and remote Texas.

“The Musical Vanity Boxes” is the sweet story of two young girls helping make money for another kid’s gambling ring. What appears to be an innocent, childish foray into capitalism becomes grim as the reader understands the reality of the girls’ situation and the situation of the people who partake in their gambling games.

Berlin’s collection is peppered with the sublime of the southwest states. Settings evoke loneliness in the face of desolate landscapes — the harsh drylands outside Albuquerque, New Mexico — but the characters also struggle with horrible situations in which they have no control.

“The Adobe House with a Tin Roof” is the story of a 19-year-old wife living in a rented house with her self-obsessed musician husband. She faces problems getting a plumber to install piping, getting her husband to help with an annoying neighbor and getting mice to stop plaguing her house. All of the story’s men mock her and leave their problems for her to solve in a lonely, suffocating tale of strangled domesticity.

Two especially striking stories were “Andado: A Gothic Romance” and “Lead Street, Albuquerque.” “Lead Street” opens with Rex, an abusive husband, criticizing the narrator’s husband’s work of art at an exhibit opening party.

“There was a keg of beer and everybody was pretty high. I wanted to say something to Rex about that crack. He was so blasted arrogant and cruel. And I wanted to kill Bernie for just smirking. But I just stood there, letting Rex stroke my behind while he insulted my husband.”

The prose, narrated by the abused wife’s friend, portrays every character with fear and hesitation to exert agency over anything, even when Rex dumps casserole in his wife’s lap and tells her how to sleep — on her stomach, because her nose was an imperfection.

“Andado: A Gothic Romance” is unnerving in it’s matter-of-fact portrayal of child predation. A 14-year-old American girl in Chile enjoys a bougie trip to a rich Chilean businessman’s estate. Their language is charged with uncomfortable sexual energy as they ride horses and read novels by the fireplace. At one point, the narrator points out the language the girl used to describe a visit she once took into a mineshaft.

“The smell of the mines. Dank, dark. How it felt to go into the earth itself. The shock when she saw her first open-pit mine at Rancagua, the Anaconda copper pit. The vast gash of it, the rape of it.”

The story is a haunting tale that shows how tragedies quite simply happen — no heavy-handed intentions on the abuser’s part until the culminating moment.

If there’s anywhere these stories falter, it’s in their constant description of minute character details and thought explanation. The reader doesn’t need to know when and where every character sits down to smoke their cigarette — these types of sentences bog down some moments.

Though Berlin may not have lived to see her work published in volumes, “Evening in Paradise” rings with a lively voice, touched by trace hints of magic. These narratives offer wonderfully moving tales and, in my mind, secure Berlin as a figure whose work demands attention.