“Don Quixote” by Miguel de Cervantes has been called “the Bible of humanity” and the “universal novel.” Published in 1605, this two-part book is the work of fiction that single-handedly created modern Western storytelling. Quixote’s effect is everywhere — he's in Buzz Lightyear from "Toy Story" and Billy Pilgrim in "Slaughterhouse Five."

Four hundred years later, its importance has not diminished, and its comedy continues to rival modern-day humorists.

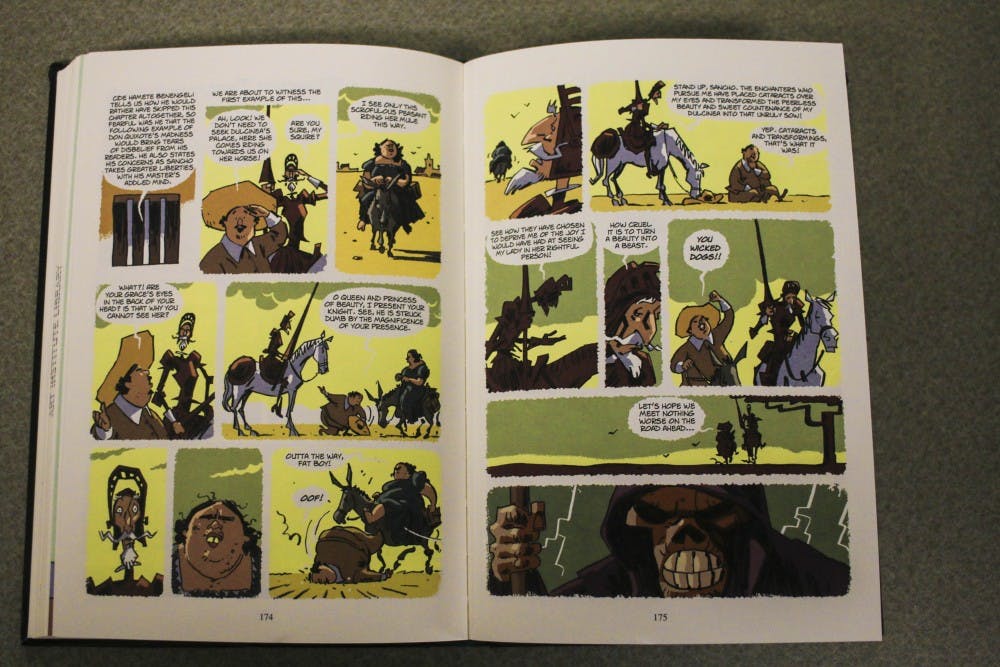

In this bestselling novel of all time, chivalrous Don Quixote believes he is the epitome of honor, value and virtue. He battles knights and monsters in Middle Ages Spain with his stout squire Sancho Panza for company, in his knightly quest to win honor for his mistress Dulcinea del Toboso.

None of this is actually true. Quixote is old, delusional, ego-gorged and lacks any grandeur. His rusted armor is over a hundred years old, and the monsters he fights are actually windmills and watermills. Dulcinea del Toboso doesn’t exist. Yet, he truly believes he is an actual knight-errant of Spain.

“Don Quixote” was written amidst a flood of romance novels — stories of strong, brave knights and heroic quests and damsels — all romanticized, idealized, unrealistic. By writing about a character trying to embody these traits while possessing none of them, Cervantes not only pokes fun at ye olden popular romances but thrusts an unprecedented idea into literary culture: What is real? So edgy, so postmodern.

Some argue through the contrasting perspectives of the delusional Quixote and the realistic Sancho, Cervantes suggests the idea that “reality” is what one makes of it. The reader sees both sides of each situation they find themselves in — romantic versus grounded. For example, Quixote and Sancho see a collection of windmills in the distance.

“Look there, friend Sancho Panza, where thirty or more monstrous giants present themselves, all of whom I mean to engage in battle and slay,” Don Quixote said. “It is God’s good service to sweep so evil a breed from off the face of the earth.”

“What giants?” Sancho asked.

Hilarious moments of illusion and reality clash throughout the novel. They reveal how easily our common reality can be distorted by one’s personal beliefs. From there, many interesting questions arise — is Quixote’s “reality” any less legitimate than Sancho’s? Is happiness under the spell of illusion “true” happiness?

As if reality wasn’t confusing enough within the novel, Cervantes claims that the real author of “Don Quixote” is not himself, but a man named Cide al Hamete Benengeli. The meta references make the reader continue to question the legitimacy of the narrative they originally trusted as real.

Literary debates aside, the story is extremely accessible in its comedy. No one needs a deep understanding of literary theory to enjoy seeing Quixote steal a shaving basin with the belief it’s a helmet.

I don’t care if you’re an avid reader or not. Read the novel. Read the graphic novel. Watch one of the many movies. Many Western stories you enjoy arose from Quixote. You can find it for free in countless places online. “Don Quixote” should be devoured and wielded as a testament of truth and reality in the face of the pretty lies we tell ourselves and others.