In Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel, a man with the mind of a child observed an instructor giving lessons to a colleague. People call this man by different names: Frankenstein, the Monster or the Creature.

By eavesdropping on these lessons, the Creature learns the English language, the history of the world and the way human society is. He begins to gain an awareness of his grotesque deformities.

“Was I, then, a monster,” the Creature said to himself. “A blot upon the earth, from which all men fled and whom all men disowned?”

The pop culture icon known as Frankenstein celebrates its 200th birthday this year. He murdered children and stars on cereal boxes. Most people think he’s a slow, shambling mass with neck bolts and green skin. Others believe he’s intelligent, articulate and athletic.

Who, or what, is the Creature?

Inception and first appearance

The idea came to Shelley one night in the summer of 1816, after Romantic poet Lord Byron challenged her to come up with a horror story.

“When I placed my head upon my pillow I did not sleep,” according to Shelley's introduction in a later version of the novel. “I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together.”

From this initial image, she wrote and then published the novel on January 1, 1818. The Creature was born.

In this earliest story, he was agile, intelligent and desirous of love. In most ways, he was superior to humans — scaling glaciers and unfazed by extreme weather.

“He learns to read ‘Paradise Lost,’ speaks Miltonic English,” IU Professor Monique Morgan said. “As English majors know, that’s pretty sophisticated.”

He wanted, more than anything, to be perceived fairly beyond the hostile judgments of his appearance.

“The thing that’s denied to him is community,” IU Professor De Witt Douglas Kilgore said. “Being part of a family. As a result, he finds himself in opposition to humanity.”

Creating the modern Creature

The Creature first found the stage only five years after the novel’s publication, when an 1823 staged version of “Frankenstein” portrayed him as mute and blue-skinned.

In the first act, Victor proclaims defiantly as the Creature comes to life: “It lives!”

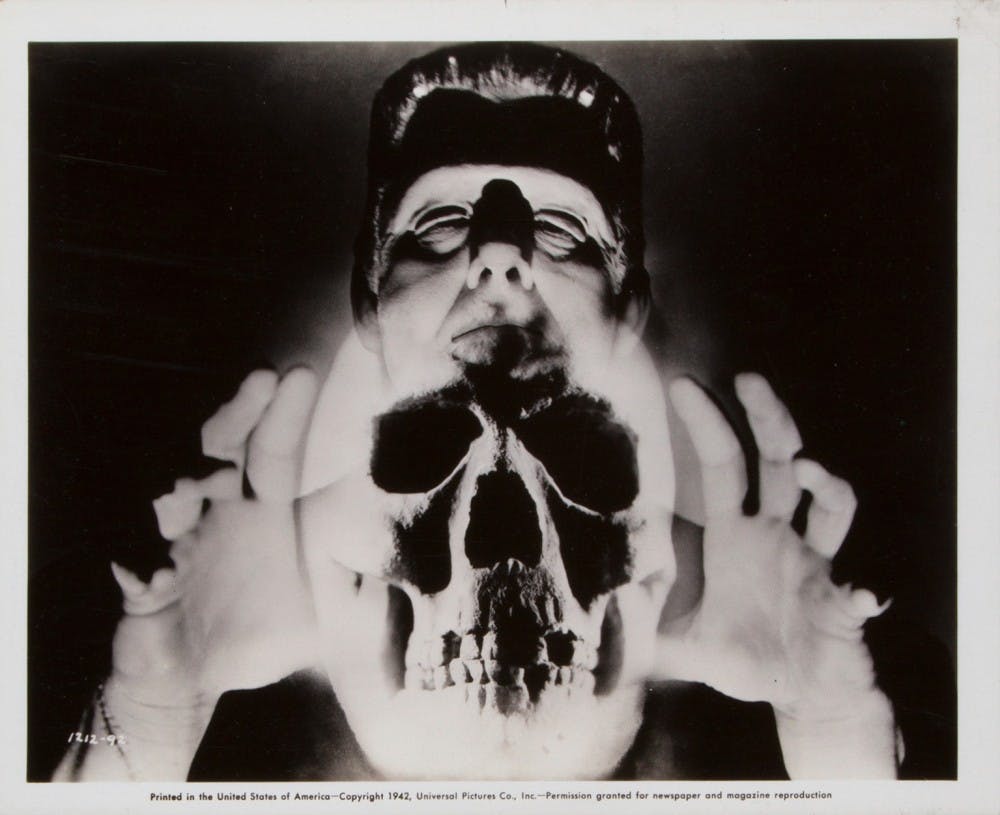

On the Creature's 113th birthday in 1931, he became a movie star in director James Whale’s film, “Frankenstein.” Actor Boris Karloff’s portrayal as ‘Frankenstein’s monster’ is the origin of the shambling Creature character with neck bolts and green skin.

“That’s what we identify as Frankenstein,” Kilgore said. “Though the actual Frankenstein is his creator.”

In 1971, General Mills introduced Franken Berry cereal, starring a cartoonized version of the Creature on the front of the box. Since then, he has been the subject of children's shows and comics, and an icon of Western entertainment.

Difference and otherness

Morgan said European society in the time Shelley was writing was based on prestige, wealth and connection to royal bloodlines. Like Shelley, the Creature had none of those, and realized he’s nothing.

“That then creates an opening for readers to think about other kinds of social outcasts,” Morgan said. “The poor, and people who have been disenfranchised for various reasons.”

According to his review of the novel, Romantic poet and Shelley's husband Percy Shelley believed the novel's intended moral was, “Treat a person ill, and he will become wicked.”

Conversely, Morgan said some characters in the novel believe the Creature’s otherness is inherent in his being.

So, who is the Creature? Is he a human who’s experienced ill fate, a harmless children’s character or an inherently evil creation?

“Shelley doesn’t give us any straightforward, easy answers,” Morgan said. “That leaves a lot of room for readers and viewers of film versions to come up with their own speculations and answers about it, which makes it feel more alive.”

Whether watching Saturday morning Frankenstein cartoons or reading the 200-year-old novel, Kilgore said the Creature and what he stands for is something we as a culture choose to keep in mind.

“The original story captured a part of modern experience that’s still relevant,” Kilgore said. “It’s a modern fairy tale.”