When a wave of heroin overdoses shook Bloomington last week, it had one hopeful footnote: no reported deaths.

A decade ago, a spike in overdoses like this one — BPD responded to nine overdoses in a three-day span — would have left fatalities in its wake, Bloomington Police Department Capt. Steve Kellams said.

The difference has nothing to do with the heroin.

Police still don’t know what about the drug caused the overdose cluster, Kellams said. What has changed is the availability of naloxone, the drug used to combat overdoses of heroin and other opioids.

“There is no doubt this would have been a lot worse without this life-saving tool out there,” Kellams said.

Naloxone, a drug that counters opioid overdoses by blocking certain brain and nervous receptors, wasn’t widely available in Indiana even a few years ago.

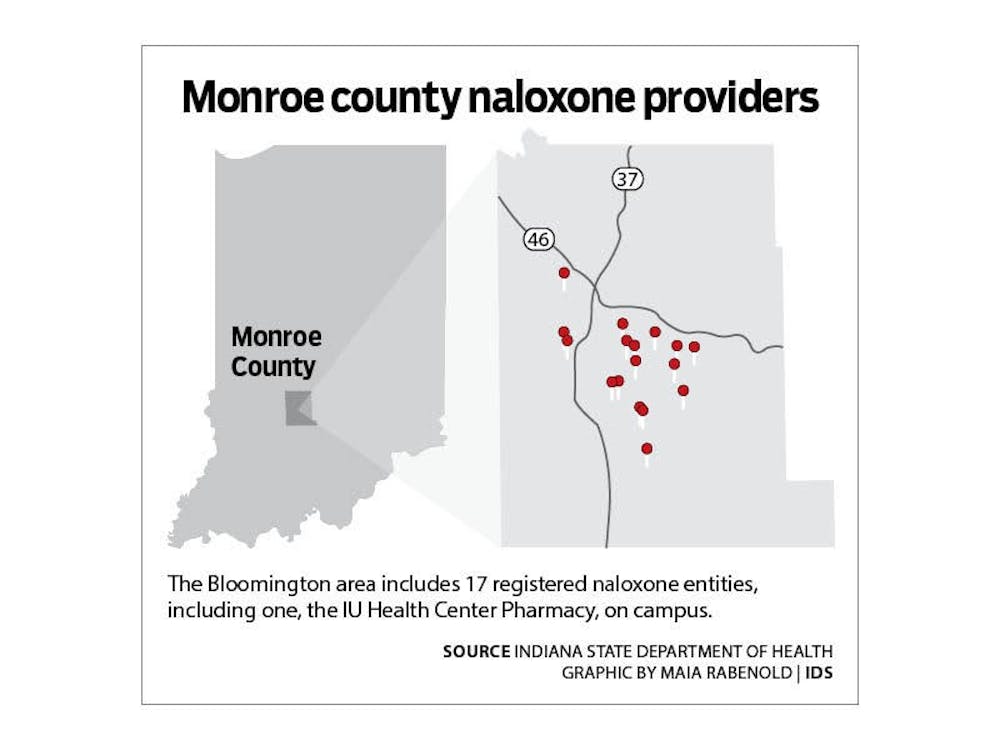

Now, Indiana has hundreds of registered naloxone entities. Seventeen of those are in or near Bloomington, including one on campus, according to the state health department’s map of entities, and the local harm reduction project Indiana Recovery Alliance distributes naloxone as well.

According to a press release sent out in the midst of the overdose spike, the project has distributed more than 5,000 doses of naloxone throughout Indiana since September 2015, and it has received reports of 500 overdose reversals associated with that distribution.

“Kind of the problem is there aren’t on-demand treatment options available right now,” IRA Director Chris Abert said. “Often times, people will just say, ‘Don’t do heroin,’ as if it’s that simple. Our job right now as we try to get these reforms and options is to keep people alive.”

Bloomington’s other naloxone providers fall into a variety of categories. Many are pharmacies, most of which are CVS or Kroger stores. A CVS pharmacist said Monday she couldn’t comment officially on naloxone distribution, and a supervisor did not return a request for comment..

Also among the pharmacies is the IU Health Center Pharmacy, which has a supply of naloxone available for students to take freely and anonymously.

Jackie Daniels, director of OASIS, IU’s drug and alcohol support center, said IU received the naloxone kits last year via a grant and has distributed a few since.

Though heroin is a less visible issue on campus than in the rest of Bloomington, Daniels said the kits could still prove useful in medical emergencies involving combinations of prescription opioids and alcohol, a more likely scenario among students.

At any rate, she said, most students who have taken kits did so after hearing about them at OASIS events, and they’ve taken them not because they’re actively using opioids but because they want to be prepared in emergency situations.

“To me, drug overdose, alcohol poisoning and drug addiction are public health issues, and just like we’d have auto defibrillators in the SRSC for an emergency, it may never be used, but to have it on hand is good practice,” she said.

The Monroe County Health Department, another registered naloxone entity, distributes naloxone to both individuals and other resources. Kathy Hewett, the department’s lead health educator, said its supply is funded by a state grant.

People can pick up the drug from the health department after going through a brief training session, which Hewett said usually lasts about 10 minutes. The department also distributes naloxone to BPD and Positive Link, IU Health Bloomington Hospital’s HIV and AIDS outreach program.

All of BPD’s officers are trained to use the drug, and all 68 of its patrol officers carry it, Kellams said.

He advised against seeing naloxone as a solution to even a single overdose, though. Its effects can wear off while the recipient still has overdose levels of heroin in their body, which means they could overdose for a second time.

Because of that, bystanders who apply naloxone should still call emergency services.

Still, Kellams said, the drug’s availability has improved BPD officers’ ability to combat at least one aspect of the opioid epidemic.

“It’s a service that is nice for officers to have,” he said. “Life saving is one of our key components.”

The opioid epidemic is ravaging Indiana. Read about one father's battle with pain pills and heroin here. Read about one mother's struggle with her son's addiction here.