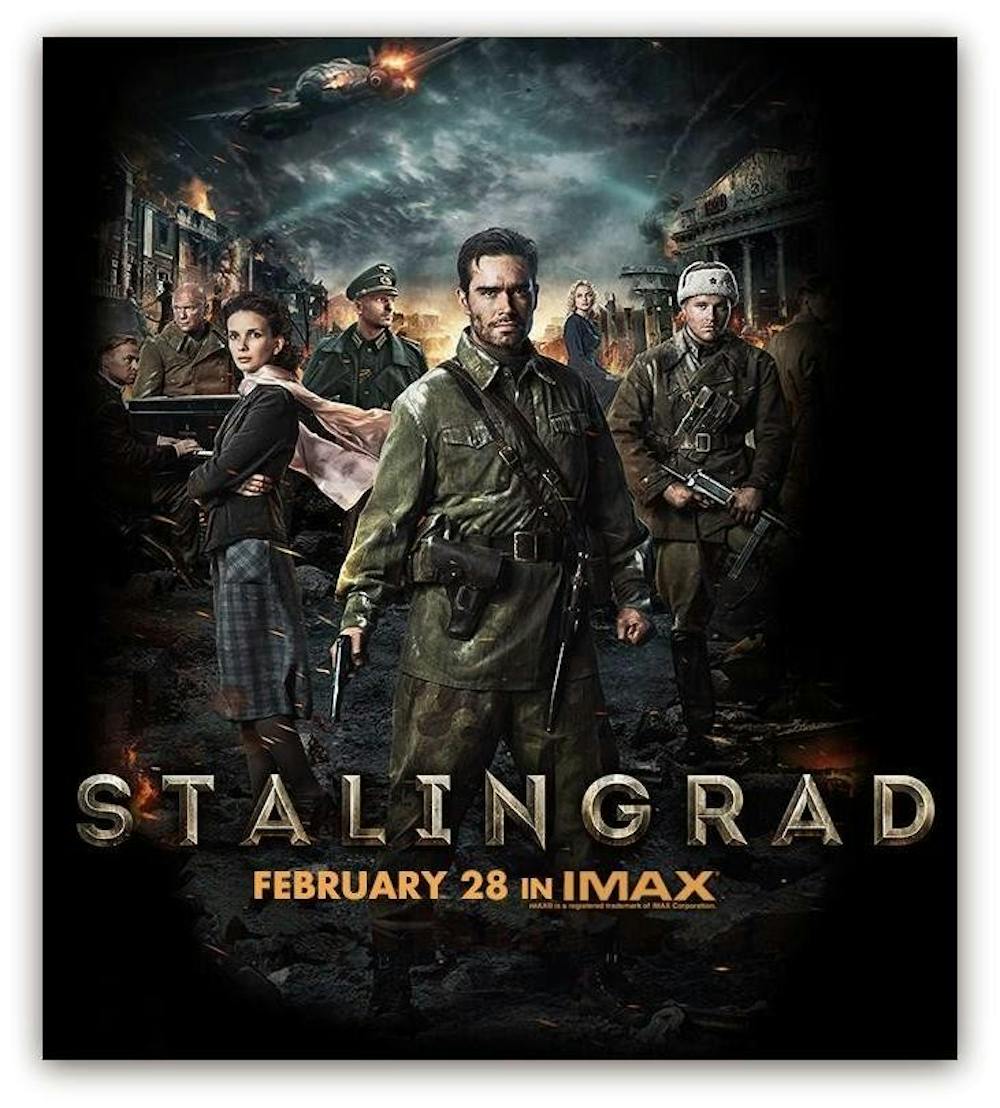

“Stalingrad,” director Fedor Bondarchuk’s flash-bang approach to the most bloody battle of World War II, initially premiered in Russia back in October.

That could explain why the film is so heavy on the pro-Russia propaganda. In preparation for the Sochi Olympics, Western eyes were beginning to turn towards the motherland. Bondarchuk, capitalizing on the interest of foreign viewers, was probably eager to showcase the merits of his country in a spectacle both patriotic and dazzling.

The first Russian movie to be shot entirely in IMAX 3D technology, “Stalingrad” is so giddy to show off its technology that the results are almost unwatchable. Every shot of the desolated city is so exaggeratedly rich in detail that the eye wearies of the spectacle in moments, subjecting the exhausted viewer to frame after frame of lucid rubble, blurred by the incessant drone of ash that drifts through the sky like charred strips of film negative.

How much pulverized bric-a-brac can you buy with a $30 million budget? Too much, the camera reminds the audience each time it races across the city, projecting a landscape like baroque chiaroscuro in Technicolor: inky smoke and luminous fire, ash-white buildings and dark, brooding Russian faces.

Bondarchuk’s patriotic hubris makes no apologies for such flagrant over-dramatization. Melodrama is the catchphrase of the film. Granted, this is an easy pitfall for war epics to fall into, but “Stalingrad” fails to recognize when enough is enough.

When the film finally does pause to allow a shaky plot to emerge from the furious tempo, the change is hardly noticeable. Following the soldiers’ horrendous crossing of the Volga River into the Nazi-occupied city, audiences are introduced to five reconnaissance troops who have holed themselves up in an abandoned apartment.

Though they bear slightly different names, they are all more or less the same person — filthy and battle-hardened and ready to shoot the man next to him if he dare use the Motherland’s name in vain.

There are stabs at character — one of the soldiers is shy of girls, another was a former opera star — but these details, emerging only after absurd moments of violence, are ultimately meaningless. Personality means nothing when there are Nazis to kill.

From there, the five men establish a base against the Nazis and face off for the next two hours. These intermittent firefights are arguably the worst moments of the film — less the handiwork of a director who claims to have read “all the history of the Battle of Stalingrad” than the renderings of a teenager who has played too many violent video games.

Weirdly enough, beneath all the stylized gore and the absurd slow motion pans of soldiers dodging bullets or slashing throats, the film tries to sell itself as a love story between the soldiers and a young woman residing in the apartment. This is not really worth exploring — she is a human element and little else.

It’s doubtful that this parallel could have ever worked, and it’s certainly not possible to buy this relationship on the terms that Bondarchuk offers. The director’s concerns are focused on war.

It’s not difficult to say how Western audiences will respond to Stalingrad. Special effects and production value can’t blur its two-dimensional nationalism.

However, with recent conflicts in Ukraine and Russia’s mounting pressure on the country, the film’s patriotism may bear a more ominous connotation than it did back in October. For the soldiers of Stalingrad, protecting their country amounted to protecting a bunker against foreign invaders.

Seventy years later, the line between protector and invader is not quite so easily drawn.

'Stalingrad'

Get stories like this in your inbox

Subscribe