Before I delve into one of the most controversial trials in recent history, let me make one thing clear.

I can’t fit centuries’ worth of strife and debate about race in America into a single column.

To have a true understanding of where our concepts of race come from and where we stand today, I’d have to do years of research. You could even argue that, as a middle-class white female, I have no right to talk about issues of race. But I’ve written many columns about these issues, because I feel that they need to be addressed, and that there aren’t enough people trying to address them.

All the knowledge I’ve gained about what the minority experience is like comes from reading and hearing the perspectives of the people who do have a right to talk about race and decide what does and does not constitute racism — our nation’s minorities. I don’t claim their knowledge as my own.

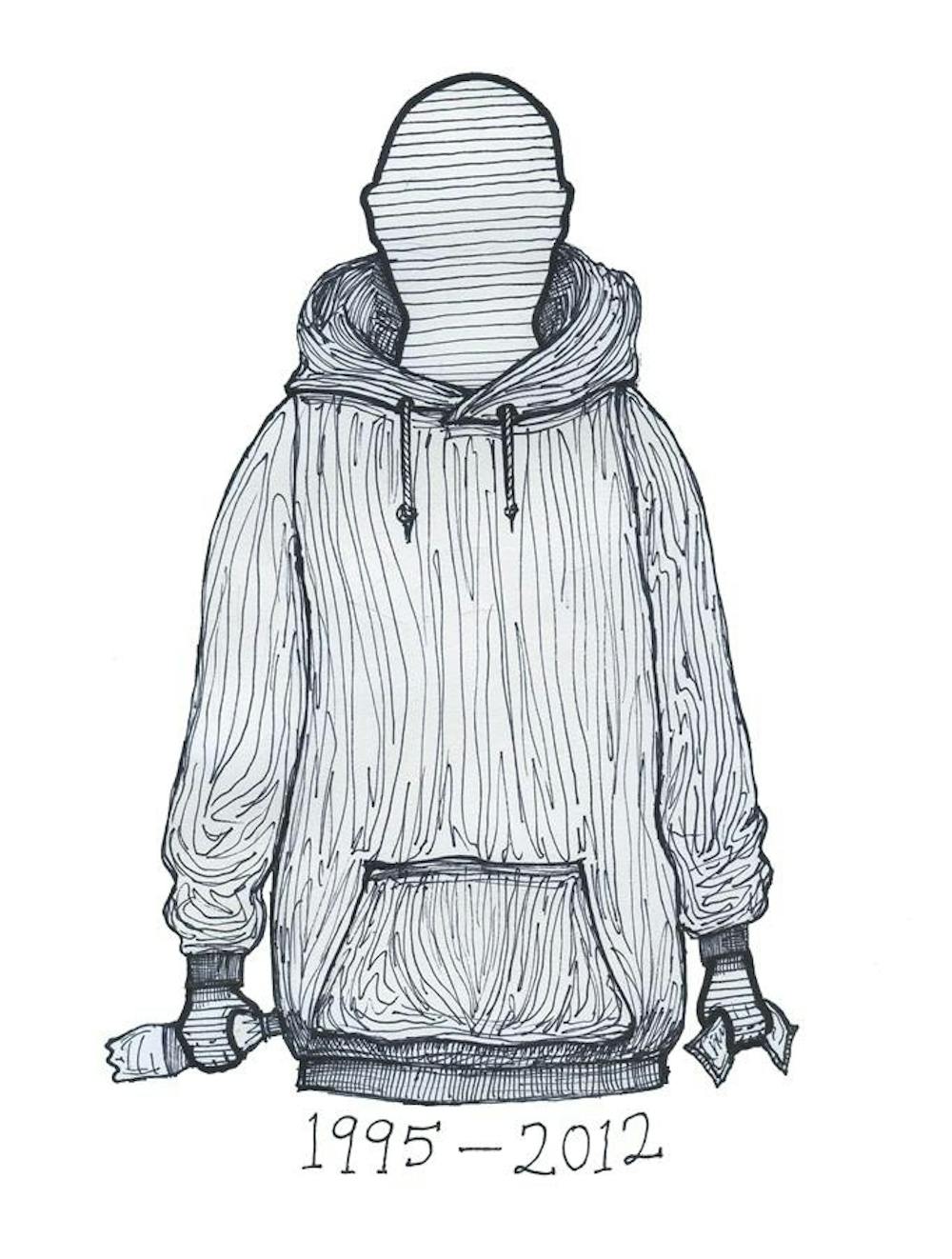

So say what you want about the case of George Zimmerman and Trayvon Martin, but it’s absolutely impossible — and incredibly ignorant — to argue that race played no part in the shooting or the proceedings.

This is because it is impossible to argue that race plays no part in the daily lives of most Americans.

Before Zimmerman fatally shot Martin, their Twin Lakes neighborhood was on edge because of a string of eight burglaries, most involving young black males. Zimmerman and neighborhood residents were on the lookout for young men that looked like Martin, and many speculate this is the reason Zimmerman felt compelled to take vigilante action against him, even when advised not to.

Zimmerman was playing the hero, protecting his neighborhood against the villains — generalized as young African-American men.

But was this just cause for killing a child? Justifying Zimmerman’s actions with this mentality is like deciding all bicycles are evil because you’ve crashed yours a few times.

Even Florida’s morally and legally murky “Stand Your Ground” law doesn’t stand up to the simple facts of the case. Martin was a fairly small minor, carrying no weapons, pitted against a much larger, older man with MMA training and a gun — a man who followed him at night. It was no contest from the beginning.

“Stand Your Ground” might somehow work as a defense in the courts of Florida, but as far as much of America (and this author) is concerned, it all boils down to the toxic cycle of racism, whether Zimmerman was part-Hispanic or not.

He was the product of our current racial climate, the embodiment of how much of our nation currently feels about young black men.

Of course, it’s difficult to argue any of this in court. That’s why Zimmerman was acquitted: because of reasonable doubt. It was completely legal. It just wasn't right.

This is a case in which the American legal system has worked against true justice, and we must remember that just because something is law, does not necessarily make it just.

In a recent examination of “Stand Your Ground,” the Tampa Bay Times found the law has been alarmingly successful for those that kill and later claim self-defense.

Applications of the law vary wildly, they found, and almost completely depend the personal opinions of the deciding judge (or in some cases, the jury). The Times called the results showing the law’s astonishingly inconsistent application “shocking.”

Although the application of the law problematically varies, the one constant in most cases has been that 70 percent of those who kill and claim “Stand Your Ground” walk free, even though the large majority of the victims were unarmed, and the large majority of the killers had guns.

Killers can get off scot-free even if they shoot someone who is retreating, or leave the scene and return later with the sole intention of shooting an unarmed man — which has happened multiple times.

Moreover, while roughly 59 percent of those who kill a white victim walk free, 73 percent of those who kill a black victim walk free. That’s a 14-percent difference — not an insignificant discrepancy. The numbers don’t lie.

Our system of American laws has become so twisted that, in states like Florida, you can get away with killing someone if you have an expensive enough legal team and a malleable enough judge or jury.

And, it can be argued, if you’re not guilty of being young and black.

Supporting this theory, just after Zimmerman was acquitted, a young black Florida mother was sentenced to 20 years’ time for firing a gun in self-defense. Marissa Alexander fired warning shots to defend herself against an abusive husband

attempting to attack her. The shots did not hit or injure anyone. She tried to claim “Stand Your Ground” and was denied. She now faces prison.

If anything demonstrates just how convoluted and unjust our legal system has become, it’s the juxtaposition of these two cases. A man who killed an unknown, unarmed teenager walks free, while a mother defending herself faces jail time.

You can argue what you want about how the law does or does not apply to each case, but when you look at the bare, simple facts, it’s obvious something in our legal system is broken.

Not guilty does not mean innocent, and applications of law do not guarantee justice. And when you put guns in the hands of people stirred into a violent frenzy and tell them they can shoot first and think later, nothing good can come of it.

When the law becomes unclear, as we’ve seen throughout our nation’s history, it is the little man that suffers — minorities and historically oppressed groups of all sorts. Although privileged white Americans are hesitant to admit it, our country has a history of subjugation.

In the past, laws were made to support and legalize it.

Now, supposedly, laws are made to prevent it from happening.

But we still find a way, because it’s this sort of oppression that keeps those making the rules in power. Even if we’re not aware we’re perpetuating it. Those that insist we should just forget about racial, sexual and other differences are usually those that haven’t had to experience the other side of things. It’s easy to suggest that black people should stop “complaining” about racism when you’ve never been black (and don’t even get me started on the myth that is “reverse racism”).

We may not even be conscious of it, but everything from Supreme Court rulings to pop culture portrayals and incarceration patterns proves how far we still have to go in the arena of American racial equality. Dr. King’s dream is nowhere close to being fulfilled.

We see that poignantly in the case of Trayvon Martin and George Zimmerman and in our nation’s reactions to it.

Some wounds go too deep. They continue to fester.

Incarceration rates for black men, especially young black men, are far higher than they are for white men. About 1 in 15 black men will be incarcerated in their lifetime, as opposed to 1 in 106 white men.

This isn’t because black men are inherently more violent.

This is because of the environment we, as a nation, have created over hundreds of years — an environment that puts non-white-straight-male groups at a disadvantage in many places, an environment in which being a woman, being gay or, in this case, being black, is often an incredible handicap.

Especially in the case of America’s minorities, we’ve created and perpetuated a cycle of poverty, violence and incarceration that is difficult, if not impossible for some, to escape. Every day, through our laws and our media, we keep the cycle alive.

The young black men who burglarized Martin and Zimmerman’s neighborhood, although responsible for their own decisions, were likely a product of this toxic environment. Zimmerman seems to be a different product of this environment — someone who has learned to fear and generalize the young black men it has created.

We see this toxic cycle close to home in Indianapolis, which has been experiencing a wave of violence, with incidents usually involving young black men targeting other young black men. I’ve seen this toxic cycle in my own neighborhood in Indy, where a neighborhood alert was once sent out after three of my African-American friends stood in my cul-de-sac and chatted with me.

It’s a tricky line to tread, but the only solution to this problem lies in the middle.

We cannot ignore race, but we also cannot generalize it into becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Both Zimmerman and Martin fell victim to the treacherous cycle, to the roles our culture has created, pitting us against one another.

One ended up dead because of it.

If we want change, we must resist these violent roles that our society seems determined to push us into, but respect every individual group’s history, heritage and struggles while doing so.

We must be willing to admit our own mistakes and acknowledge the mistakes of our

ancestors and peers.

We can only live without this violence if we learn to respect our differences, and even to celebrate them, rather than living in fear and trying to assimilate those not like us, punishing them if they refuse.

It’s a tall order, but a worthwhile one. Look past what you’ve been conditioned to see. Question why things are the way they are. Take the time to think — really think — and act constructively.

Perhaps if we can do these things, Trayvon will not have died in vain.

— kelfritz@indiana.edu

Column: America's racial realities

Get stories like this in your inbox

Subscribe