From his pullout bed in the middle of the living room floor, Bryan stirs beneath his soft World Wrestling Entertainment blanket.

After a few minutes, his stomach starts to growl. He ate a bowl of cottage cheese before going to bed last night so he wouldn’t be hungry this morning, but it didn’t work.

Soon, he’s up, the buzz of the alarm clock pulsing as he and his younger sister Amber roll off their bed mats.

Amber’s stomach hurts. It rumbles. It contracts. It whines. She’s hungry and would rather have her breakfast right away, but she has to wait until they get to school, where she’ll eat a free hot breakfast. Today she’s craving waffles, but she won’t get them. She hasn’t had waffles in a long time.

Bryan and Amber’s mom, Tammy, coaxes them into the silver truck before the rain soaks their clothes. She’s not working, so she has the time to take and pick them up from school most days.

In the car, Bryan thinks about lunch, his favorite part of the school day. By the time school starts, lunch will only be four hours away.

The words “hungry children” usually evoke images of children in Africa, stomachs bloated and rib cages protruding from thin flesh, but there are hungry kids who go to school less than two miles from IU’s campus. Fairview Elementary is within throwing distance of gourmet restaurants, organic grocery stores and dorm cafeterias overflowing with ethnic foods.

Like 92 percent of the students at Fairview, Bryan and Amber take part in the free and reduced lunch program. The rate at Fairview is significantly higher than the state average of 45.3 percent, according to the Indiana Department of Education’s 2009-10 school year data.

The National Food Research and Action Center survey results place the national average at 63 percent, a number that is likely higher than what most presume.

The program at Fairview serves foods such as French toast sticks for breakfast, apple slices for a midday snack and chicken fingers for lunch.

But they can’t always provide for their students. Saturdays and Sundays turn into a time when food, especially fresh fruits and vegetables, becomes an uncertainty.

Bronwyn Shroyer, the social worker at Fairview, spends her days making sure students are taken care of, which includes finding them food.

In front of her desk, she holds a box of Rice-A-Roni and Hamburger Helper, asking a female student which meal she would prefer to take home. The boxes hang heavy in Shroyer’s hands. She wishes she could give her both.

When the students leave school grounds, she wonders if they’ll have enough food for dinner that night.

Shroyer keeps extra snacks in her room inside a large cardboard box. Today, the box is empty. She has already passed out the extra stash of granola bars and prepackaged cookies.

But today is also Thursday — backpack day.

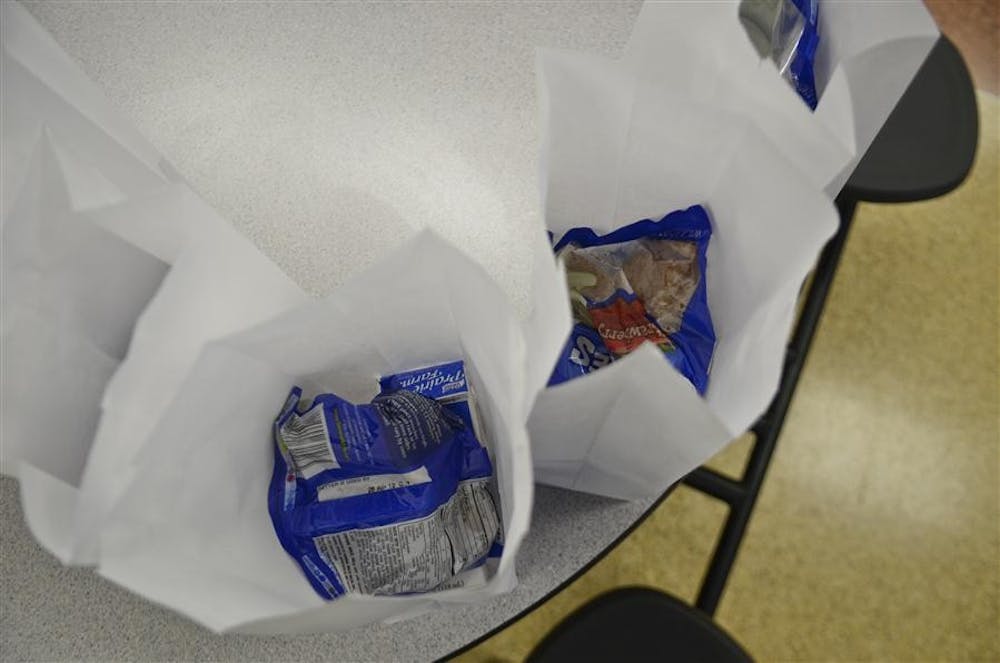

The Community Kitchen of Monroe County, a nonprofit organization that provides daily food services to those in need, delivers backpacks of weekend food supplies for students to eat throughout the weekend.

Each backpack contains around eight pounds of food. There’s protein — a can of chicken, tuna, beans or peanut butter; a grain — Quaker oatmeal, pasta and miniature boxes of cereal; maybe a meal helper and always fruits and veggies, which sometimes come in cans or plastic cups. With the exception of a fresh produce item that is purchased some weeks, all of the food is donated.

Thursdays at Fairview are like Christmas morning. Kids linger outside Shroyer’s door to peek at their bags but will wait to get them until they’re called down with their class.

“Can I get my backpack now?” a young boy asks Shroyer.

“Not yet,” she says, a soft laugh masking her tired eyes.

He knows he has to wait, but that won’t stop him from asking her nearly 20 times that day if he can get his backpack. He speaks up, saying that he’s hungry, and she worries about whether he gets enough food at home.

While six schools participate in the Backpack Buddy Program, Fairview became the program’s first school in August 2005.

The Community Kitchen approached Jennifer Kamstra, who was Fairview’s social worker from 2005 to 2008, about its idea to help students in need of food during the weekend. Based on the number of students who received free or reduced lunches, Kamstra said Fairview was an obvious first choice.

They asked Kamstra to identify certain children she thought were in need of extra assistance and have parents fill out permission slips to enroll them in the program.

When it started, 30 students signed up to receive backpacks. Now there are 43 backpacks, which Shroyer estimates help feed 100 people.

***

It’s raining outside. It’s actually pouring. But Julius Lee, operations manager at the Community Kitchen, has 43 backpacks to bring inside Fairview, and the fat drops of rain are an insignificant detail.

For kids like Bryan and Amber who woke up this morning feeling hungry, what he’s dropping off matters.

From the car parked on West Seventh Street, he slings bundles of backpacks around his arms, thumping up the wet concrete stairs and pushing open the rain-streaked glass doors.

The beads of rain cling to the fibers of his knit cap as he drops the first load of backpacks on the ground of Shroyer’s bright orange office. He lets out a breath before he gets the second load of backpacks, which will be followed by a third, until the floor is covered with the bags, each marked with a number in slightly faded white ink that corresponds to a certain child. Amber and Bryan are number seven.

The last thing Lee plops down is a plastic tub full of pears in Ziploc bags.

“When children have food to eat, they are psychologically better at whatever tasks are set before them,” Lee said. “We’re just helping make it easier for a parent or guardian to prepare a balanced meal.”

Bryan and Amber share the duty of retrieving backpack number seven. This week, it’s Amber’s turn.

When her class is called down to get their backpacks, her classmates zoom down the hallway, jumping down the stairs and singing songs about how it’s Thursday. Amber walks slowly and drags her hand against the wall.

Amber’s second grade teacher, Joshua Livingston, knows the majority of his students eat both breakfast and lunch at school. These two meals may be all that some students will receive that day.

During free time, kids pull out miniature boxes of Honey Nut Cheerios, but Amber runs to play monkey-in-the-middle with two of her classmates. However, Livingston notices times when she will rest her head on her desk, stare off into space and sit quietly. He assumes the signs of fatigue relate to being undernourished. He says Amber is humble and knows exactly what she has. She keeps her thoughts about hunger to herself.

When Amber gets to Shroyer’s office, she walks over to her desk and stares. The other girls in the room snatch their backpacks and start rummaging through to see what they got this week. Maybe they have Cheetos or Chef Boyardee, but please, let there be macaroni and cheese.

Shroyer encourages Amber to go get her backpack, but Amber can’t seem to find it. She crawls over the bags and turns them over sideways. She’s convinced it’s missing.

Shroyer’s intern, Holly Paul, grabs the one near Amber’s foot and hands it to her. “Here it is.”

She blushes and throws one strap over her shoulder. “Thank you,” she whispers.

At the tub full of pears, Amber pulls out the sack on top and wrinkles her nose.

“I hate pears.” Her eyes soften. “But I’ll take some because my Mom likes them.”

Amber and her dad used to pick pears in their neighbor’s yard. There were always extra pears, and the neighbors didn’t seem to mind. Even though Amber doesn’t like to eat pears, she had fun because she picked them with her dad.

Two years ago, they had to move from their trailer to a house.

Amber swings the bag of fruit in her hand. “That’s when we stopped picking pears.”

***

Amber thinks healthy foods have a lot of vitamins — grapes, chocolate milk, apples. She says drinking milk makes your muscles strong, but she’s not sure why. As long as something tastes good, she’s happy to eat or drink it.

When the family’s not in the kitchen, they’re in the living room. It’s the room they like the best. There are three bedrooms in the house, but the four of them choose to sleep in the living room some nights. Bryan and Amber sleep on the floor. Mom and Bladen, her youngest son, sleep on the two couches.

Spending time in the living room reminds them of their dad, Bryan.

For six years, their dad suffered from diabetes and congestive heart failure. Toward the end of their dad’s life, he got to the point where he could hardly walk, so they moved his bed into the living room. That way, he could watch his kids and eat dinner with them. He died last year on Thanksgiving.

Bryan and his dad, whom he was named for, shared a love of Salisbury steak. Mom gets Bryan the frozen Salisbury steak dinners that he can pop in the microwave. They used to buy the meals in packs of five.

“We only buy four now,” Bryan says, his eyes following his swinging feet that don’t quite touch the ground.

***

Outside of Fairview’s cafeteria, the Wildcat Café, the kids wait at the door with their hands cupped, applying a pump of Purell before they can get their lunch.

Two women place cartons of fish sticks, turkey with noodles and french fries onto each Styrofoam tray. The kids can grab containers of salad or grapes, but nearly everyone takes a small plastic cup filled with cheesecake.

Around circular tables, Bryan and the other fourth-grade boys pretend to wrestle, throwing in the occasional old school dance move, such as the sprinkler. Multitasking is essential.

But lunch is only 30 minutes, and Bryan is a slow eater, so it seems shorter. Midway through his noodles, he looks up to find his classmates gone.

At Amber’s table, between bites of fish sticks and grapes, she talks about her dad with her friend.

The other girls giggle as Amber tells her friend how she used to eat strawberries with her dad. Her friend slowly nods her head, but her gaze is fixed on the girl shouting about the pudding.

Amber was happy with today’s lunch, but now, she really wants strawberries. But it’s not in their Backpack Buddy.

With her pink school bag over her shoulders and her navy-blue Backpack Buddy hanging from her elbow, she runs out to the silver truck, slings her backpacks into the backseat and jumps in.

Soon, it will be dinner time, and she’s already hungry.

The high cost of free lunch

Local elementary school struggles with high poverty

Get stories like this in your inbox

Subscribe