Gustav Potthoff’s is “the most American of stories,” said Jon Kay, director of Traditional Arts Indiana. Kay will curate “Tell People the Story: The Art of Gustav Potthoff,” an exhibit that is part of the Fall 2011 Themester, “Making War, Making Peace.”

As an immigrant seeking freedom from financial and physical oppression, Potthoff, a World War II veteran, achieved the American dream, Kay said.

“He worked hard and created a life for his family in a small Midwestern town,” Kay said.

Upon retiring, Potthoff became a prolific self-taught artist, compelled to carry the story of his time as a prisoner of war and keep the memory of his fellow prisoners alive, Kay said.

“This is not commemoration. This is not celebration,” Kay said. “This is really about telling people that this happened. There are still people unaccounted for.”

The outdoor exhibit will be from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. now until Sunday in the Indiana Memorial Union garden, which is near the Tree Suite Rooms.

From 12:15 to 1:15 p.m. Saturday, Potthoff will be present to speak with visitors.

The exhibit consists of 10 vinyl panels, eight of which are 39 inches by 72 inches and two of which are 4 feet by 4 feet. Photographer Greg Whitaker took the images of Potthoff’s artwork for their outdoor display.

The son of a German father and an Indonesian mother, Potthoff was raised in a Dutch orphanage in Indonesia from the age of two. After 15 years there, he enlisted in the Netherlands Army Tank Battalion.

When World War II began, Potthoff was captured by the Japanese.

At the prisoner of war camp where he lived, he was forced to work on the infamous Hellfire Pass and the bridge over the River Kwai.

These projects were part of the Thailand-Burma Railway. Its construction was considered a war crime — 16,000 of Potthoff’s fellow prisoners perished while building it.

“At a time when I was thinking about what I’d do after high school, he was already in a prisoner of war camp,” Kay said.

After he was liberated from the camp in 1945, Potthoff went on to fight during the Indonesian National Revolution. From 1955 to 1962, he worked in the Netherlands as a tank repair mechanic until his military retirement.

It was then that he emigrated to the United States with his young family. Sponsored by the Downey Avenue Christian Church of Indianapolis, his family settled in Columbus, Ind. He worked at Cummins, Inc. until his retirement in 1987.

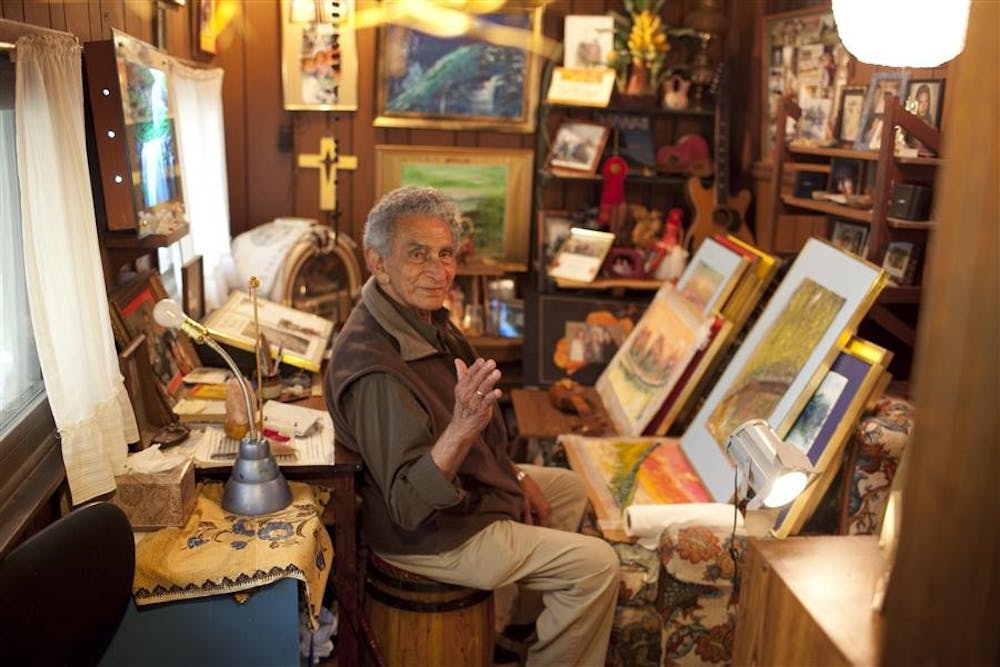

Now that he is retired, he paints with brushes and sponges. He’s a fast painter, and his artwork is not for profit, Kay said. Instead, he gives his artwork to schools, libraries and museums to keep the memory of his friends alive.

Kay said Potthoff buried one close friend, an Australian, in a shallow jungle grave only two feet deep. The guards wouldn’t allow him to dig any deeper as it was a “waste of labor.”

But despite all of the atrocities and brutal conditions Potthoff has endured, Kay found him to be at peace and without anger. Instead, his artwork serves as a mnemonic device.

Most of the paintings have a variety of spirits that live in the jungle looking down on him, Kay said. These spirits are ever present, a remembrance of his friends.

“He has very much forgiven people for what has happened, but he doesn’t want it to continue,” Kay said. “Forgive is not the same as forget.”

AN AMERICAN STORY

Brigitte Potthoff still has the blue trunk that carried her family’s possessions from the Netherlands to the U.S. in April 1962. She still has the receipts for the boat tickets for herself — then a two-year-old child — and her parents, Adele and Gustav

Potthoff.

When they stepped onto the soil of “America, land of the free,” her parents had $150 in their pockets, their life savings. Since then, they feel privileged to have lived the American dream.

Potthoff and his wife have lived in the same house since 1966.

When Brigitte was growing up, her mother worked the second shift at the hospital, so her father was her primary caretaker in the evening. While he never shared anything specific about the war when he tucked her into bed, she knew he was an orphan.

It bothered her to think he wasn’t wanted. Later, she realized that because of the war, his mother couldn’t takecare of him or his younger sister.

As she grew older, her father told her more about the exotic but brutal camps.

TIME IN THE JUNGLE

He rode elephants. He built bridges. He swam in the rivers.

The elephants helped carry the heavy teak wood, which was used to make the railroad sleepers. The swimming, Brigitte later learned, was not recreational.

To construct the cement foundations of the bridge, he had to dive underwater. Brigitte swam in the River Kwai when visiting Thailand in 2006, and “the current is unbelievable,” she said.

Potthoff had to use buckets of sand as weights to hold him down so he would not be swept away. After the prisoners came out of the water, they often had to remove the leeches from their bodies, only one problem of many in the camp.

Potthoff suffered from beriberi, dysentery, cholera, malaria and a snakebite. He still bears the snakebite scar, and he can’t donate blood because of the malaria.

For food, the prisoners had rice or rice porridge. When in the jungle, they would watch to see what monkeys would eat and follow suit, as the roots and plants they selected were likely to be safe for humans.

“It wasn’t until I got older that I pieced things together,” Brigitte said. “In my 20s, I realized that he was put in a ship for a month or so.”

Potthoff described it as a “hell ship” to Brigitte, for that’s what it was — thousands of prisoners of the Japanese packed in for transport to camps. Food was inadequate, and the conditions were severely unhealthy. Hundreds died.

These ships were often not marked as carrying prisoners of war, so the Allies would sometimes bomb them. Potthoff was fortunate to not be sunk.

Brigitte believes her father was able to survive not only because of his strong spiritual connection, but because he is Asian.

As he grew up in Indonesia, he was used to scorching, humid weather nearly year round and the monsoon seasons, when the rain would last for months.

“He is a very, very strong individual,” Brigitte said.

GENTLE ARTIST

Potthoff has always been a quiet man, and a little self-conscious because of his thick accent, Brigitte said.

“To be able to speak through his paintings has opened a way to communicate for him,” she said.

She said she loves his bright, vivid colors. Someone once pointed out to her that he never uses black. No matter how dark his time as a POW was, his paintings are still full of beautiful color.

She asked him why there were flowers in the trees.

Wild orchids grew high in the trees of the jungle, her father replied.

Brigitte saw these orchids herself in a 1994 trip to Thailand with her mother. They walked through what had been Hellfire Pass, and there grew the same orchids her father saw during the war.

“Amid all the ugliness and death, he saw beauty, and he remembered that,” Brigitte said.

Her mother lost much during the war, too, but neither of her parents has lost their zest for life, she said.

When she thinks of all her parents have been through, she feels tremendously grateful for what she has.

“Because of them, I’m here in this great country and wonderful community, and I’m thankful,” Brigitte said.

Her mother, Adele, recently celebrated her 79th birthday, and Potthoff will turn 90 next year.

When they arrived in America nearly 50 years ago, everything was new and beautiful and big, and the people were friendly, Adele recalled. Financially, they struggled for the first year or two — but, Adele said, “Being young, you don’t notice that.”

Adele worked as a nurse, and Potthoff, with his experience working on tanks and engines for the military, worked for Cummins until his retirement.

When asked about her husband’s artwork, Adele paused.?“Well, I’m a very difficult critic,” she said. “It’s OK, but I’m a difficult person.”

The artwork has helped him to cope with the problems of his younger years, she said.

“When you get old and retire, you have more time to think about what has been, and that’s when the memories come up,” Adele said. “When you’re young, you don’t have time.”

Now that he has retired, Potthoff volunteers at the Atterbury-Bakalar Air Museum in Columbus, Ind.

The veteran visionary: IMU displays memories of war as art

Get stories like this in your inbox

Subscribe