Editor's Note: IDS reporter Sarah Hutchins analyzed Bloomington and IU police departments' records about all "sex/rape" crimes reported in the past 10 years and compared them with statistics from Bloomington's Middle Way House, a non-profit domestic violence and rape crisis center. This story is based on interviews with experts and more than 700 police reports.

Numbers can’t tell the whole story of sexual assault in Bloomington. They can’t describe the full-body shock a victim feels in the wake of an assault. They can’t include the hundreds of victims — mostly female, but also male — who don’t want to put their bodies on display for law enforcement or a jury. They can’t capture the lingering pain.

But the numbers can still tell a story.

More than 700 people filed reports of sexual assault — a crime that includes rape, attempted rape and any form of unwanted sexual contact — with Bloomington and IU police departments in the past 10 years.

These crime reports, as well as information from Middle Way House, can shed light on a misunderstood crime. They can confront the confusion surrounding consent. They can discredit myths many of us have internalized from a young age.

The numbers give us strength. They can help us fight back.

The healing system

While some victims choose to report sexual assault to a police agency, most survivors don’t use the legal system to heal. Compare Middle Way House statistics with those of local police, and the magnitude of underreporting becomes clear.

In 2010, the Bloomington and IU police departments recorded 80 cases of sexual assault. During the same period of time, Middle Way House on-scene advocates responded to 291 calls. In 45 of those cases, an advocate counseled a victim in the emergency room.

The dramatic difference in numbers helps explain why the U.S. Department of Justice has called sexual assault the most underreported crime in the country.

While Middle Way House doesn’t distribute statistics about the number of victims who file a police report, crisis intervention services coordinator Tina Cornetta explained that many victims do not go to the police.

“I can understand why the legal system is not always conducive to healing,” Cornetta said.

When victims ask about reporting an assault, Cornetta said, she explains how the case moves through the judicial system. Sometimes victims worry reporting will put them in more danger. In other cases, a survivor doesn’t want to go through the experience of explaining what happened.

“After you’ve experienced trauma it’s understandable that you don’t want to tell your story over and over again,” Cornetta said.

After an assault, Sexual Assault Crisis Service Counselor Ann Skirvin explained, the mind and body act to protect the victim. The mind can shut down, Skirvin said, and survivors can go into a state of shock. She compared the experience to standing on a frozen pond.

“There is anger and sadness under the ice, but you don’t have access to it,” Skirvin said. “It’s instinct to act like it never happened and move on.”

These coping mechanisms can get in the way of reporting. Sometimes the speed at which police and prosecutors work isn’t right for a survivor.

“The general legal system doesn’t always work well in these cases,” Skirvin said. “It can work on a timeline that’s counter-intuitive to what’s healing.”

Monroe County Deputy Sex Crimes Prosecutor Rebecca Veidlinger said there are good reasons to report. Prior allegations of sexual assault have helped her negotiate plea deals in later cases.

But even if she can’t file charges, Veidlinger said, the process of reporting can empower survivors.

“People are proud that they spoke up and did it for themselves,” she said.

A dangerous safe haven

Stories of strangers attacking women in the night characterize discussions of sexual assault, but maintaining these myths could put us at risk.

Sexual assault finds us in the places we feel safe. It reaches into homes and offices. Reports show up from grocery stores, restaurants and even churches.

Police reports show that the majority of sexual assaults don’t happen in parking garages or isolated areas. In 10 years, no one has reported a sexual assault in Dunn Woods.

Assoc. Dean of Students Carol McCord said she’s witnessed parents and students perpetuate false ideas of sexual assault. Earlier this year — after reports of several sexual assaults appeared in the media — parents called McCord to express concern about the safety of their daughters.

McCord told them the University was worried about the spike in reported crimes, but that she was equally concerned about the risk all college women face among their own group of friends.

“Parents were mad when I said that,” McCord said.

Many of the parents said they didn’t want to talk about girls who get drunk and make decisions they regret, she said. They saw acquaintance rape — the most common form of sexual assault — as a lesser crime, one undeserving of attention.

“I can put out more lights and I can put out more police,” McCord said. “What I can’t do is change the cultural attitudes people have about this.”

But the emergency blue lights around campus haven’t been used to alert police about an assault in at least 10 years, McCord said.

The lights and buttons were designed to help people feel safer and make students aware of their surroundings. However, their placement in isolated areas furthers myths about where assaults take place.

“If I could put a blue light in every bedroom,” McCord said, “maybe I would get somewhere.”

Friends and strangers

The majority of sexual assaults take place among acquaintances, and many of these crimes come down to a question of consent.

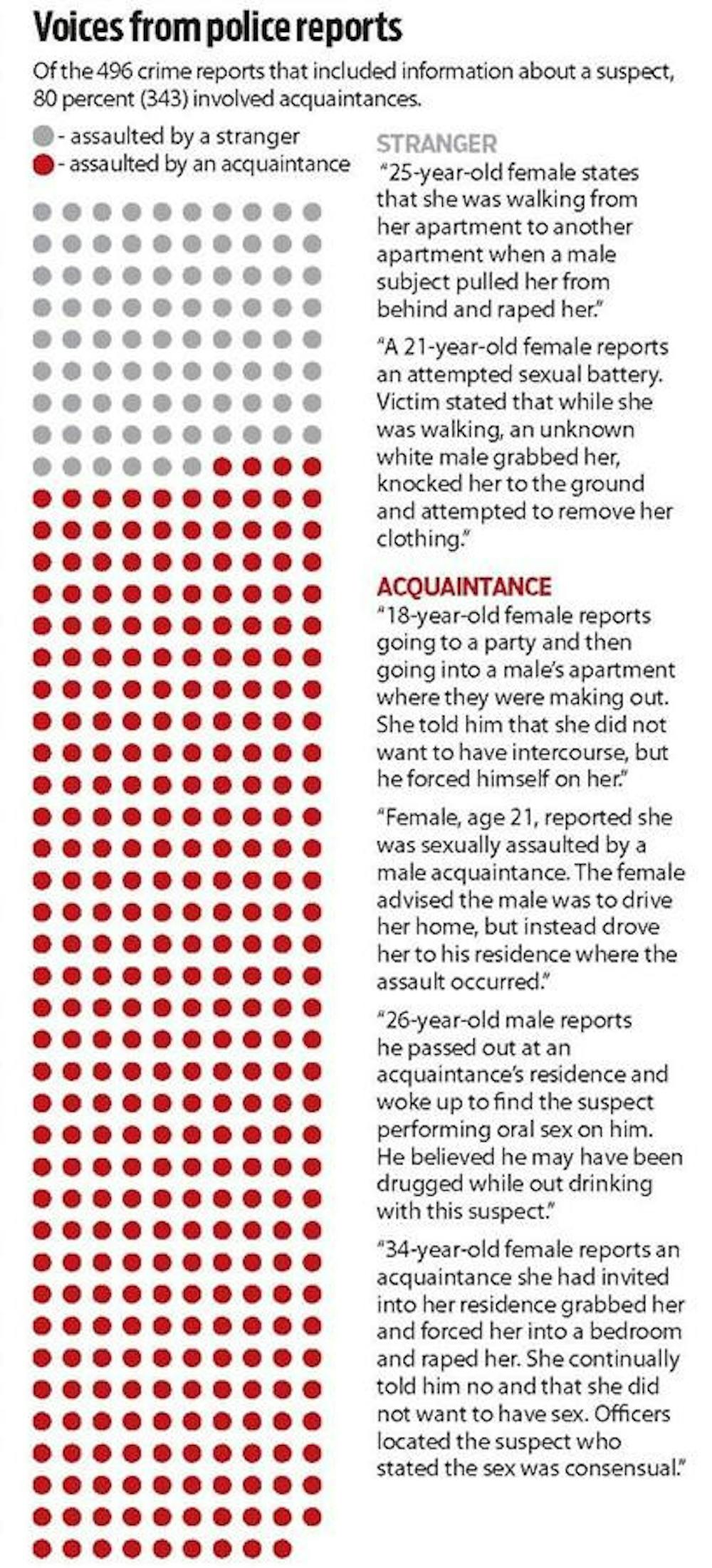

Eighty percent of reported sexual assaults in Bloomington were perpetrated by acquaintances, while only 20 percent involved strangers.

Police reports describe boyfriends holding down and raping girlfriends, employees groping coworkers and husbands assaulting wives.

Beneath the surfaces of these cases lies the question — or confusion — of consent.

One woman told police she was raped by an acquaintance “with whom she’d had consensual sex in the past.” According to the police report, when police talked to the suspect, he didn’t deny they had sex but argued it was consensual.

Kristen Jozkowski studies consent as a Ph.D. candidate in applied health science. She said men and women interpret consent in fundamentally different ways.

Women, Jozkowski said, view consent as a verbal agreement. Men, on the other hand, interpret consent as a woman not saying no or not fighting their advances. For them, actions imply consent.

While most of the men who participated in Jozkowski’s consent studies understood the legal definition of the term — and necessity of verbal consent — many worried that bringing up the topic would make sex awkward.

A small group, however, saw it differently. If you ask a woman about consent, they told Jozkowski, you give her an opportunity to say no.

There is no such thing as “kind of” giving consent. As Rebecca Veidlinger, the deputy sex crimes prosecutor, explained, consent is not a one-time action.

“Just because I gave you $10 today doesn’t mean you can steal $10 later,” she said.

Excerpts from cases

STRANGER

“25-year-old female states that she was walking from her apartment to another apartment when a male subject pulled her from behind and raped her.”

“A 21-year-old female reports an attempted sexual battery. Victim stated that while she was walking, an unknown white male grabbed her, knocked her to the ground and attempted to remove her clothing.”

ACQUAINTANCE

“18-year-old female reports going to a party and then going into a male’s apartment where they were making out. She told him that she did not want to have intercourse, but he forced himself on her.”

“Female, age 21, reported she was sexually assaulted by a male acquaintance. The female advised the male was to drive her home, but instead drove her to his residence where the assault occurred.”

“26-year-old male reports he passed out at an acquaintance’s residence and woke up to find the suspect performing oral sex on him. He believed he may have been drugged while out drinking with this suspect.”

“34-year-old female reports an acquaintance she had invited into her residence grabbed her and forced her into a bedroom and raped her. She continually told him no and that she did not want to have sex. Officers located the suspect who stated the sex was consensual.”

Who can I call?

If the accused is an IU student:

Use the campus judicial system by calling the Office of Student Ethics and Anti-Harrassment Programs at 812-855-5419.

If I want to complete a rape kit:

Go to the IU Health Bloomington Hospital or IU Health Center. You do not need to report a crime to have a forensic exam (also called a rape kit). Evidence collected through the exam can be stored anonymously for up to one year.

If I want a counselor:

Set up an appointment at the Sexual Assault Crisis Service by calling 812-855-5711 or use the 24-hour crisis line: 812-855-8900.

Fighting back

Get stories like this in your inbox

Subscribe