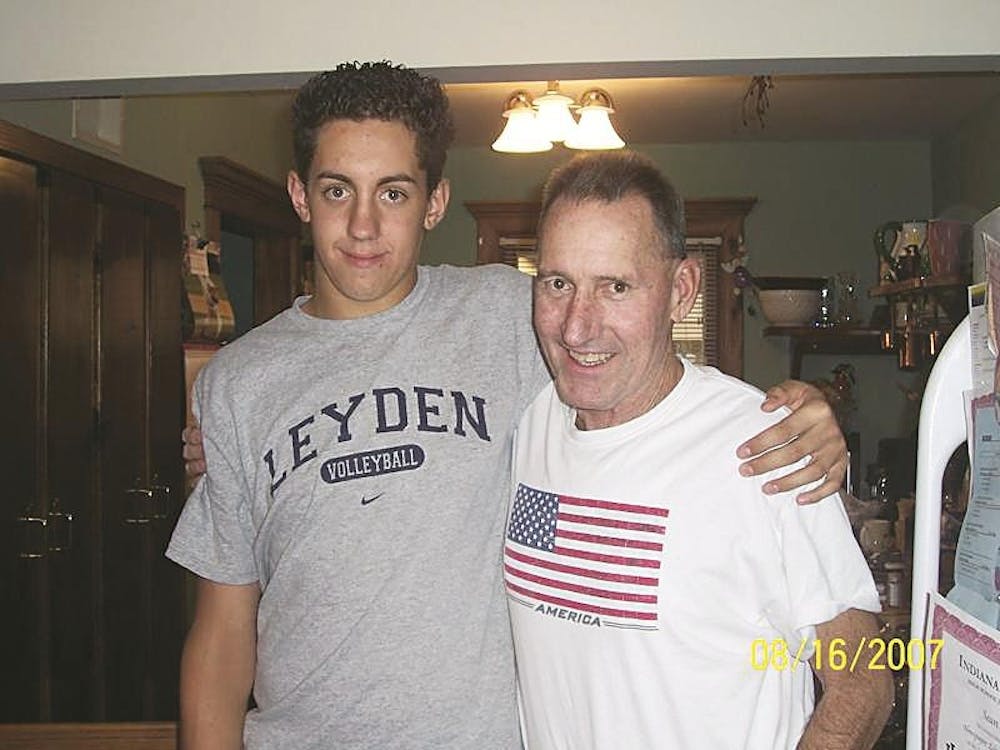

My grandfather never went to the Wall. A Vietnam War veteran, he never pressed his hand to the black granite monument and felt the grooved indents of 58,261 names. He couldn’t bring himself to do it, so I did it for him. I drove 650 miles to confront the loss – his and mine.

On the day of my grandfather’s death last March, I didn’t cry. I didn’t cry the next day. Or the next. Or even once I got home.

The day of his funeral, what struck me as I stood in his room was the painting on the wall. Painted by Lee Teter, “Reflections” depicts a man pressing his hand to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, eyes cast down in remembrance. But it is not his reflection that stands out. It is the reflection of his fallen friends reaching out, touching his palm, and sending him life that catches my eye.

It was with “Reflections” in mind that my family, friend, and I began the 12-hour trip to Washington. The ride was full of memories of good times and how Papa changed our lives.

He was about to do so again.

***

The signs tell the story.

“In Honor of Those Who Served

Please stay on the sidewalks.”

From the moment you spot the monument to the time you reach the start of the names, at the fourth slate of smooth black granite on either side, you know this is more than a wall. It is more than a representation of the Vietnam War.

I’ve never been on a battlefield, but this is what I imagine hallowed ground feels like.

The Vietnam War had roots back to the mid-1950s, but U.S. involvement escalated in the early 1960s. The number of U.S. troops peaked at 500,000 in 1968. Now, more than 40 years later, a wall with more than 50,000 names etched into its surface cuts along the grass in our capital. It is a tribute to every man and woman killed, injured, or taken prisoner in the war. But veterans know it holds a greater meaning.

“It’s also, as the designer intended, a place of healing,” says a veteran working at the Wall. “Much of the Wall symbolizes a cut in the earth, and the grass growing up to it is healing that scar that was very divisive – the war was that scar that divided our country during that period. It is a place to come and accept death. While I don’t like it, I can accept it.”

***

As I approached the Wall, I had a plan. Pick one spot. Walk up. Touch it. Remember.

It was the only thing I could think of. That print of “Reflections” in my grandpa’s back room was always the way I saw him doing it if he went.

I walked down the pathway toward the Wall. When I reached the beginning of the granite, I hesitated. Could I do this? I steeled myself. I closed my eyes.

Breathe in. Breathe out.

I gathered myself and headed to the right side of the path. I spotted a man heading toward the monument and followed in his steps. The first four black slates had nothing on them. On the fifth, the names began. I walked slowly toward the center of the monument. I read each name, taking in the chiselled letters. Then, my eyes and feet moved more quickly. It was as if I was searching for the something. The right spot. A place to stop and honor him.

I found it about halfway down the first half of the Wall, along the walkway closest to the Lincoln Memorial. I stopped. This was it. It was time to remember.

I could sense him there. I could smell his Kenneth Cole cologne. I could picture his mischievous grin, a testament to his refusal to let age bring on maturity. I could feel his vein-covered, sun-darkened skin, as I did in the days before he passed. He was there. I knew it. I had brought him with me to the place he’d never gone.

The other visitors stopped. The world stopped. Everything stopped.

Breathe in. Breathe out. Breathe in. Breathe out.

I reached forward with my right hand, just like in the painting. I looked down to my sneakers, the bottom of the Wall still in view. I felt the cool stone.

As I held my breath, something left me. All the pain, doubt, and sadness I carried with me flowed through my fingertips and into the monument. This scar in the earth brought me peace. It was more than just the Wall, though. It was him. In my head, I said something I’d said countless times before — but I had never meant it like I did at that moment.

“Thank you, Papa.”

***

Moments like this are the reason people come to the Wall. They do not see themselves. They do not see names. They see people. They see memories. They see life.

I saw my grandpa.

The experience of reaching out with a hand — reaching slowly and touching a name — lets us take a moment to reconnect with the one we miss, the one we care about. Whether on a tour or on a journey, whether seeking a meaningful experience or seeking a name, the Vietnam Memorial Wall draws people. It stands as a place where people are quiet, respectful, and reverent. These are, after all, the names of men and women who made the ultimate sacrifice to ensure others wouldn’t have to.

“Many people come down here in sorrow, and I certainly understand that,” a veteran told me. “But a little laughter can go on, too, as we remember the joviality of those people — how wonderful and young and bright they were.”

The Wall might not move. It might not breathe. It might not have a life of its own. But the people behind it, the people it represents they do. There is not one central heartbeat to the Wall, or one soul, or one face. There are 58,261 of each, calling from beyond those granite slabs and reaching out to the people who will come to see them.

They only seek one thing from those who come to visit their sanctuary. It is not to stay off the grass. It is not to keep the noise down. It is simply this: “Remember me,” they ask. “Remember us.”

Facing their wall

Get stories like this in your inbox

Subscribe