It occurred to me the other day that I could be an astronaut. I was reading a psychology book that discussed how people in various careers find happiness, and the author referred to a generic astronaut as “she.”

I had a sudden rush of excitement. “Why yes,” I thought. “I guess I could be an astronaut if I really wanted to be!”

I have become so accustomed to hearing unknown or unspecified persons referred to as “he” that subconsciously I forgot “she” was an option. My delight at reading “she” was a truly visceral reaction. I suddenly felt included, even though I didn’t realize I felt excluded before.

After more than a decade of obsession with political correctness, one would think we’d be over the sexist language debate. Thankfully we seldom use the word “mankind” to refer to all members of the human race, though this usage remains in historical contexts.

The snappy title “Ms.” means that women can be addressed without reference to their marital status. And of course, many people these days use “he or she” when referring to an unspecified person, and some even write the nifty “s/he.”

But I don’t believe we’re out of the woods yet. Using the generic masculine pronoun is still grammatically correct. True, both the Chicago and Modern Language Association style books endorse alternating generic masculine and generic feminine, but I don’t think this solves the problem. Using “she” in generic contexts is just as exclusive as using “he.”

Distinguished professor of cognitive science Douglas Hofstadter asserts that because “nobody wants to be labeled a sexist,” alternating “he” and “she” is growing more common in academic and popular circles. But he points out that just as “he” is ridiculous usage, “she” “is just a mirror image [that] doesn’t solve anything.”

Many wonder what the fuss is all about. In the past, even I have argued vehemently for the use of the generic masculine because it is “proper grammar.” But what is proper grammar, anyway?

Hofstadter points out that “grammar is invented by people arbitrarily.”

So what is to stop us from changing it?

Of course, grammar does change. Any English major who has studied Chaucer, Shakespeare or Milton will tell you the structure and use of English has changed.

As late as the 19th century, the word “resent” meant “to appreciate” or “to feel grateful for,” but now most people use it to mean quite the opposite. Rules for capitalization have varied widely throughout the history of English, and while “thee” and “thou” were once commonplace, they are now considered to be poetic in the extreme.

There is no question that language changes, but there is also no question that many people don’t like that it does.

It seems every generation blames the youth for the degradation of language, and so it comes as little surprise that 21st-century grammarians are repulsed by the thought of deliberately changing our language.

But what is the cost if we do not? Language is arguably humanity’s greatest asset, and its profound effect on our societies, cultures and even our thoughts is irrefutable.

Galileo remarked on the incredible ability of language to use a finite assortment of symbols to convey an infinite number of thoughts; Darwin later posited that the ability to “associate sounds and ideas” is one of Homo sapiens’ most distinguishing attributes.

It is the means with which we conceive our worlds. Limiting language creates limiting worldviews, whether or not we intend it to and whether or not we realize it.

In their excellent book “Words and Women,” Casey Miller and Kate Swift discuss at length the psychological effects of sexist language. For children, and especially for girls, the realization that “he” sometimes includes “she” but sometimes doesn’t is undoubtedly confusing.

While the generic masculine pronoun may mean to be inclusive, the authors point out “the assumption is that unless otherwise identified, people in general are men.” So girls grow up learning that men and boys are the norm, and women and girls are the other, the outsider, the alternate version.

It cannot be denied that this structure modifies how girls think about themselves and their possibilities. After all, even as an educated, feminist adult, it affected me. Young girls with far fewer educational and experiential resources are even more likely to be influenced by it.

When you think about it, the generic “he” should be confusing, and not just to children. As Hofstadter asks, “how can he mean she when obviously it is the opposite of she?” The problem is not whether one pronoun can encompass both the sexes, but that the pronoun does so selectively.

While pronouns might be the most common instance of sexist language, the use of “man” as a generic is common as well. We’ve reached an age where “person” is often substituted – congressperson, chairperson, etc. – but it is by no means the norm. Again, the problem is the inconsistency of when and whether women are included.

Miller and Swift quote lexicographer Alma Graham: “If a woman is swept off a ship into the water, the cry is ‘Man overboard!’ If she is killed by a hit-and-run driver, the charge is ‘manslaughter.’ If she is injured on the job, the coverage is ‘workmen’s compensation.’ But if she arrives at a threshold marked ‘Men Only,’ she knows the admonition is not intended to bar animals or plants or inanimate objects. It is meant for her.”

I think the generic use of “man” is every bit as damaging as the generic use of “he.” It may seem cumbersome to always substitute “person” (I was ridiculed during winter break for admiring the “snowpeople”) but it’s only a question of time for these words to become the norm.

After all, why is it bizarre to refer to an androgynous snow figure as a “snowperson” but completely normal to refer to all those cute girls in your dorm as “freshmen”? We’re simply accustomed to one, and not to the other.

We have come a long way in the last few decades, and if we continue to push through, it’s conceivable we may live to see a truly nonsexist English.

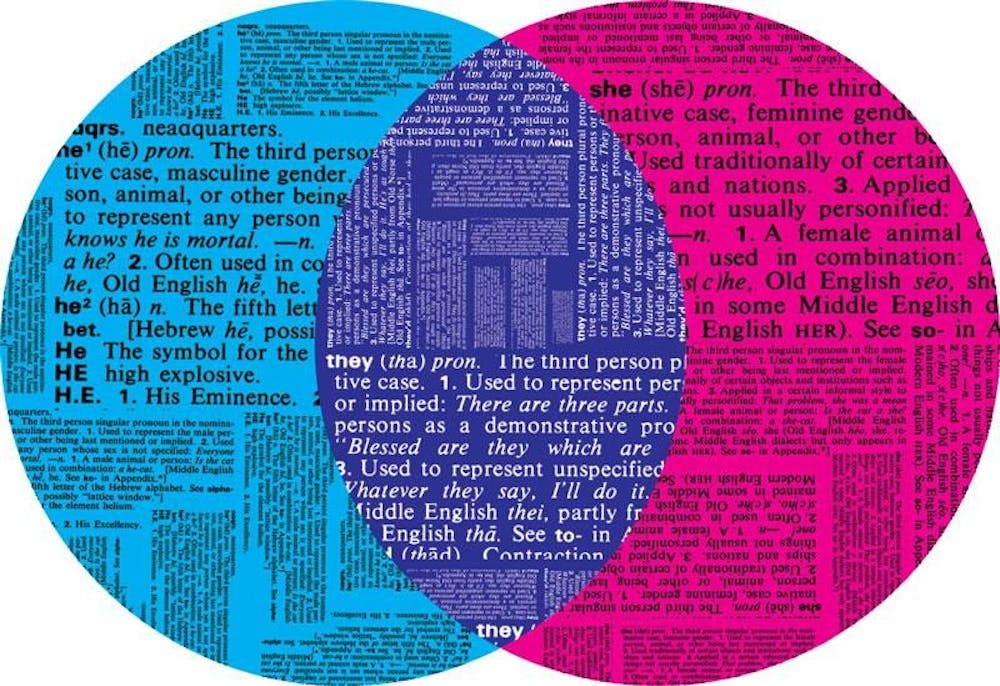

So while the style books may argue against it, I urge you to use “they” as a generic pronoun, instead of “he” (or “she”).

If you want to please everyone, you can always try pluralizing the subject, which makes the use of “they” grammatically correct by all standards. If your professor has a problem with it, they can give me a call.

One small step for a human, one giant leap for humankind

Arguing for gender-neutral language

Get stories like this in your inbox

Subscribe