The National Institute of Health awarded assistant IU biology professor and evolutionary biologist Ryan Bracewell nearly $2 million to study chromosome evolution and rapid Y chromosome degeneration.

After completing his undergraduate degree in entomology at Colorado State University, Bracewell worked for the U.S. Forest Service, where he studied bark beetles, beetles that infest and kill trees. Several years ago, he said he participated in an experiment involving the crossbreeding of the beetles.

In this experiment, the researchers were able to produce a hybrid generation of bark beetles from the original populations they crossbred, but were confused as to why the second generation could not produce any more offspring.

“We were just kind of scratching our heads you know. It was really weird,” Bracewell said. “The beetles looked very similar, and everybody thought they were the same species, but we were having problems getting hybrids.”

Upon further research, the researchers found bark beetles had peculiar sex-chromosomes, known as neo-sex chromosomes, causing the issues with the crossbreeding. Neo-sex chromosomes are sex chromosomes that are the result of fusion and degeneration of typical chromosomes, or autosomes. In January 2022, Bracewell opened the Bracewell laboratory at IU to further research this issue.

[Related: IU professor, Juergen Schieber, discovers evidence of sustained wet-dry cycling in Mars’ history]

Sam Ruffer, an undergraduate laboratory assistant for the Newton Laboratory at IU – which studies symbiotic microbe genomics – is not involved in Bracewell’s research but said chromosomes are a way for cells to store DNA, and they make replication of DNA easier during reproduction.

Ruffer said mutations relating to DNA replication issues can easily occur in chromosomes, causing conditions such as Down syndrome. However, Bracewell’s research looks into a different type of mutation, the fusing and degeneration of chromosomes themselves.

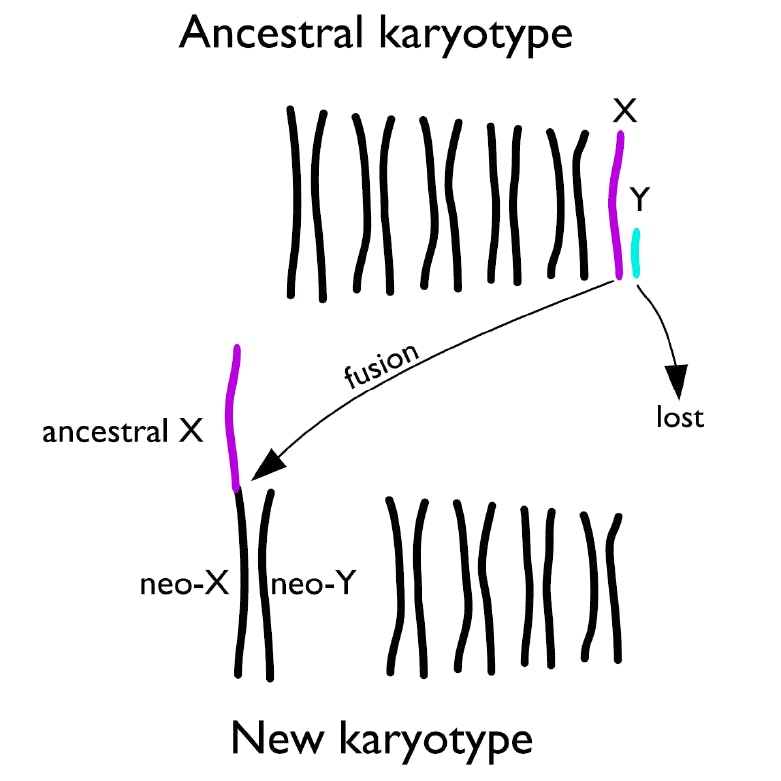

Bracewell said the phenomenon he is studying is the fusion of sex chromosomes to autosomes, non-sex chromosomes. He said in species with highly differentiated sex chromosomes such as the X and Y in humans, sometimes an X chromosome can fuse with an autosome. The other sex chromosome would be lost, and the fused autosome would degenerate into new sex chromosomes.

Bracewell said that scientists do not fully understand how chromosonal fusion or degeneration can occur without causing major problems for affected organisms, but they hope to learn more during this research.

He said his lab will primarily be studying species of fruit flies and bark beetles. He said fruit flies are particularly useful in this research due to only having eight chromosomes, compared to 46 in humans. Fruit flies are also one of the most researched species, allowing convenient genetic analysis. Additionally, he said the genetic diversity of fruit fly species will make tracking and comparing chromosomes easier.

However, he said bark beetles offer a more unique opportunity for research.

“The thing that’s cool about the bark beetles is that they have these neo-sex chromosomes,” Bracewell said. “Fruit flies have them as well, but for the system I'm working on in the beetles, it looks like the fusion was very recent.”

He said this recency, along with the ability to find multiple neo-Y chromosomes in natural populations of bark beetles, will allow his team to more effectively study what the fusion and degeneration process looks like.

Bracewell Lab researcher Camille Pushman said the day-to-day research into this topic will involve a lot of RNA sequencing to look at gene expression, the genes themselves and genome rearrangements.

As they ramp up their research, Pushman said the researchers will need to make sure they have well-researched genomes for the organisms they are looking at. Once they can get a more complete picture of genetic expression, they can more accurately compare genomic differences between different samples.

“Day to day it really involves just sitting at a computer and dealing with all this data, a lot of DNA and RNA, and making sense of it,” Pushman said.

She said this investigation will have many implications for chromosomal research but she is particularly excited about its connections to evolution as a whole.

“The great thing about this topic is that you can look at it from a lot of different lenses depending on what you’re interested in,” Pushman said. “I’m really excited about understanding about how these genomic changes give way to new changes and speciation.”

CORRECTION: A previous version of this story misstated the subject of Assistant Professor Bracewell's degree.