Recently, I’ve been reading “The Bell Jar,” a semi-autobiographical novel by the poet Sylvia Plath. I’m only about halfway through it, so I’ll refrain from synopsizing it, but know that it basically chronicles the main character, Esther Greenwood, as she slowly experiences a mental breakdown.

Just a month after the novel was published in 1963, Plath committed suicide. Many of her most famous poems, including the poetry collection “Ariel,” were published years after her death.

In a dark twist, this has only added to our understanding of her works — because the majority of her poems and letters and even journal entries were published posthumously, they are each inextricably tied to her struggle with suicidal depression. Sadly, we’ve begun defining her, in part, by her death.

In a way, she’s a portrait of the tortured artist.

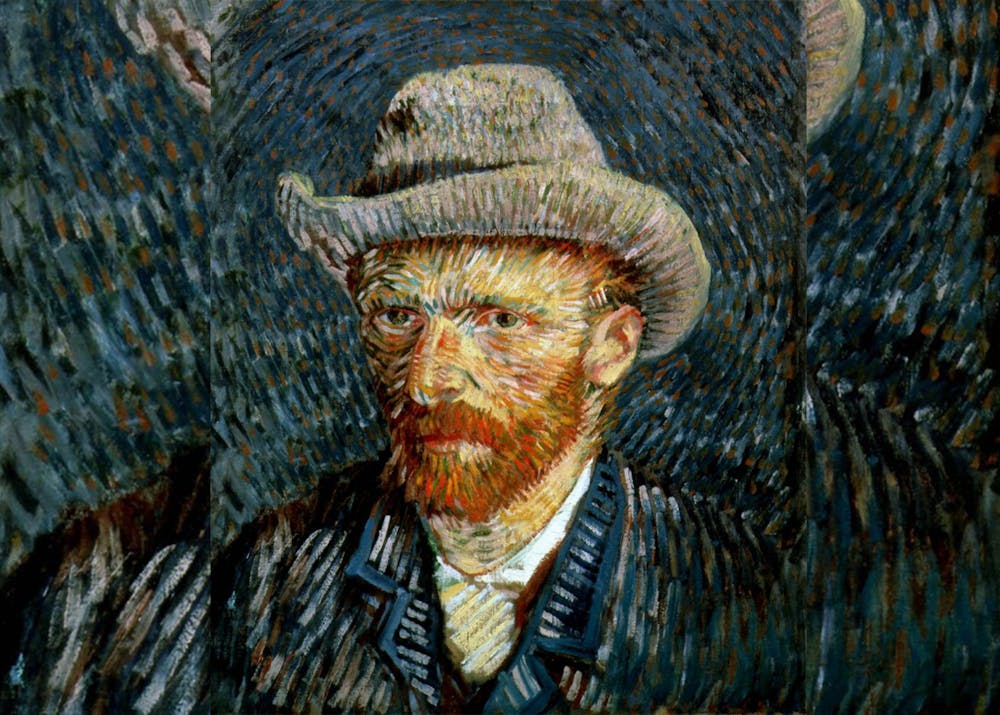

The tortured artist. The fact there’s a name for this phenomenon speaks to the fact it’s become a prevalent enough cultural trope to warrant a moniker. Vincent van Gogh is another popular example — his magnum opus, “The Starry Night,” was painted during his stay at Saint-Paul Asylum following a breakdown that ended with him cutting off his own ear.

Kurt Cobain, the frontman for the grunge band Nirvana, committed suicide in 1994 after arguably forever altering the course of popular music. He’s just one member of the so-called 27 Club, a group of artists — like Jim Morrison, Amy Winehouse and Jimi Hendrix, among others — who died at the age of 27, often by their own hand or as a result of a drug overdose.

[Related: OPINION: The mental health crisis won't end with the pandemic]

There’s a moment in the show “BoJack Horseman” when the character Diane Nguyen, a writer, discusses why she’d rather write a melancholy book of personal essays than the children’s novel she’s already proven herself good at.

“If I don’t, that means that all the damage I got isn’t good damage, it’s just damage — I have got nothing out of it, and all those years I was miserable was for nothing,” she said. “I could’ve been happy this whole time and written books about girl detectives and been cheerful and popular and had good parents.”

Andrew Neiman, the main character of the film “Whiplash” and an aspiring jazz drummer, expressed a similar sentiment: “I’d rather die drunk, broke at 34 and have people at a dinner table talk about me than to live to be rich and sober at 90 and nobody remember who I was.”

Art is a reflection of our culture, so these fictional examples demonstrate the ubiquity of this trope. Society romanticizes its tortured artists, even though researchers have agreed that mental illness is not a catalyst for creativity — and the studies that have found such a link have been criticized for a lack of varied samples.

I’ve dealt with bouts of depression and anxiety almost my entire life, so I know how easy it is to draw a link between your mental state and the work you create. It’s easy to believe, when I’m in the middle of a depressive or anxious episode, that if I were to somehow become totally and completely healthy, that my art would suffer as a result.

[Related: OPINION: Love and happiness are great, but they're not the same]

But think about it logically for a moment. My struggle with mental illness has undoubtedly been an influence on my work, but I don’t believe for a moment it’s affected the quality of it in any way. The point of art is to convey some sort of feeling, but pain and anguish and sadness aren’t the only feelings — art can convey happiness and joy and hope and be just as powerful.

The work artists like van Gogh, Plath or Cobain created weren’t visceral and powerful and even masterful because they suffered for it. Mental health awareness is a vitally important thing, and we should talk about the fact these individuals dealt with their respective conditions. But we cannot remember them solely as the artists who, in a fit of mad imagination, showed the world their genius before leaving early.

Plath’s life and death were not tragically beautiful — they were simply tragic. Her death should be a reminder of the dire effects of untreated mental illness, not a reminder of her abundant creativity in the face of romantic suffering. The same can be said of all the other artists I discussed.

These “tortured artists” deserve so much more than us romanticizing their struggles.

Joey Sills (he/him) is a sophomore studying journalism and political science.