INDIANAPOLIS – The boy is 15 years old and full of metal. Bullet fragments are stuck in his arms, his leg, his side. A rod runs through his leg, and a plate and screws hold his arm together.

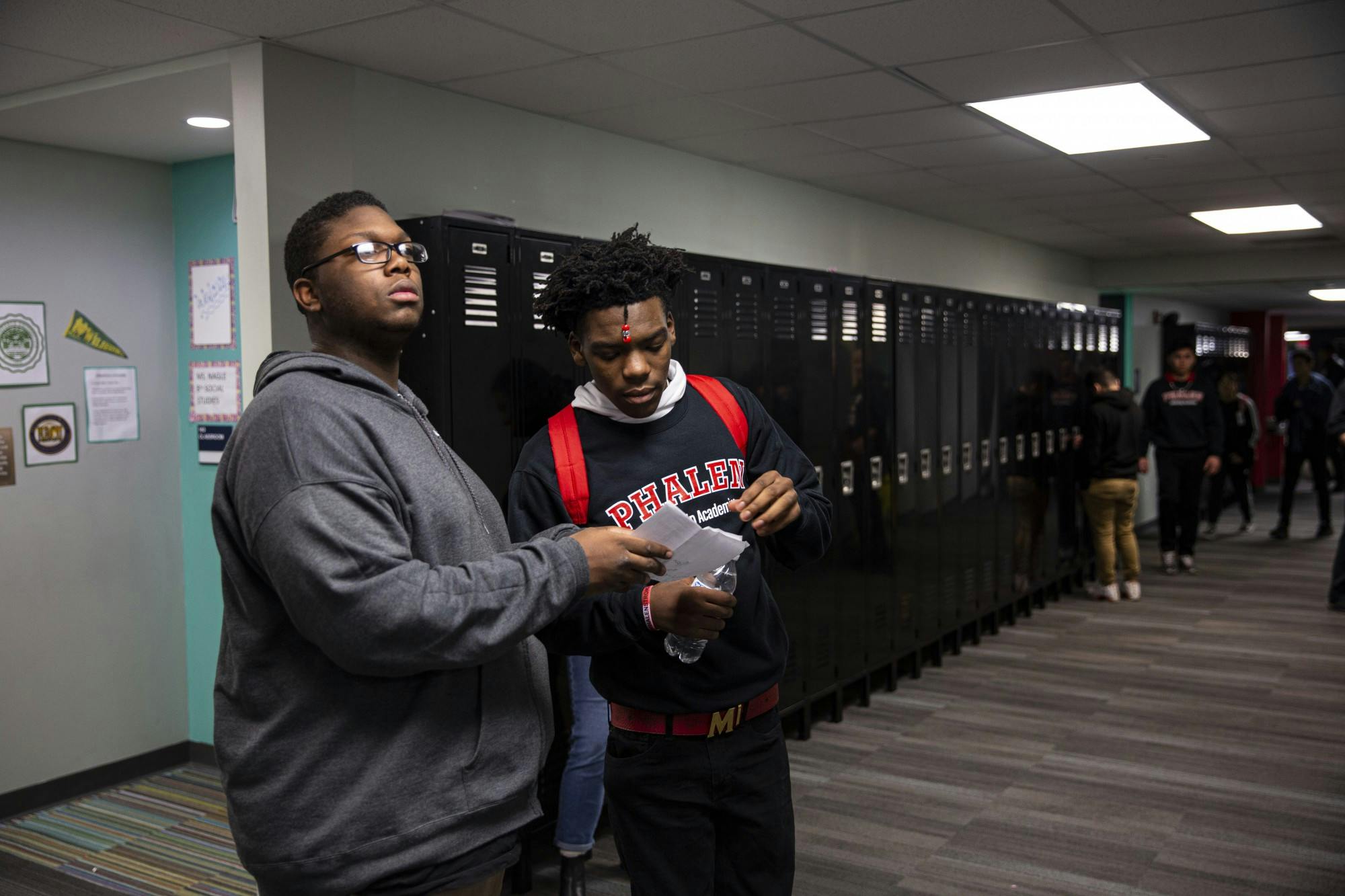

Da’Quincy Pittman limps into school on a rainy Monday morning in late February. It’s his first day back in nearly two months, and his clothes hang differently than they did before. After five surgeries, a stay in the ICU and weeks of rehab, he’s down maybe 20 pounds.

In the center of his forehead dangles a twist of hair, adorned with three beads: red, clear, red. Since that night, he’s called them his lucky beads.

He arrived after the morning rush, bleary-eyed but still careful to hold the door for his mother. The school’s chief of staff hurries over, already crying.

They flit around him – the principal, the chief of staff, his mom.

“Quincy,” one says. “I’m going to get you a schedule, OK?”

“Did you have any breakfast today?”

He shakes his head.

“Can you hold a pencil yet?”

He nods.

Da’Quincy is one of about 480 middle and high schoolers at his school on the far east side of Indianapolis. The teachers and staff hug and feed and clothe their students, but they can’t always keep them safe. Da’Quincy is one of five who has been shot in the last year.

On the night of Dec. 29, three men jumped Da’Quincy and a friend in the parking lot of an apartment complex. They threw open the doors of the car he was sitting in, shot him six times and stole the Jordans off his feet.

Indianapolis’ death toll is soaring. Over the last decade, the number of homicides climbed nearly 80%. A 2016 study found that Indiana had the highest rate of black homicide victims in the nation.

By mid-February of this year, the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department had investigated 31 homicides, nearly double the 16 investigated by the same date in 2019.

Da’Quincy’s school, the James and Rosemary Phalen Leadership Academy, charters buses to drop off students at their doors when after-school activities end. A five-minute walk to the bus stop isn’t worth the risk. One student gets picked up at his door because his bus stop is on the corner where his mother was shot and killed.

Gwendolyn Hardiman, the school’s chief of staff, has been in education for 38 years. She wears fashionable glasses and long, intricately done nails. The students call her Grandma.

“Soon as you hear it on TV you wonder, ‘Is it one of ours?’” she says.

Phalen is a public charter that opened nearly three years ago when teachers at other far east side schools got fed up with the fistfights and failings. Nicole Fama, Phalen’s 41-year-old principal and regional director, was the principal of PLA at 93, a school under the Phalen umbrella that was getting tired of sending its students to underperforming high schools.

Phalen Leadership Academies founder and CEO Earl Phalen heard about School 93’s troubles and asked Fama what was keeping her up at night. She told him she just wanted the kids to have a safe place to go after middle school.

Phalen bought a trashed, abandoned school and got to work. The James and Rosemary Phalen Leadership Academy became one of 20 Phalen Leadership Academies around the nation, including five in Indianapolis. The first year, it only offered seventh and eighth grade. Then ninth, then 10th. The plan is to expand each year to cover all of high school. Da’Quincy will be in Phalen’s first graduating class.

The school sits off of 42nd Street and Mitthoeffer Road, surrounded by a clump of gas stations and roads clotted with potholes. Grandma doesn’t stop at those stations, but she still makes sure her car never gets all the way to empty so she doesn’t have to stand outside too long.

Phalen is a structured place. Administrators and teachers always refer to students as scholars. The kids sometimes call Fama things like Ops and Federal because she doesn't mess around. She keeps a baggie of drugstore drug tests in her desk.

But Phalen is also a home. Some of the students call Fama Mom. There are washers and dryers for those who don’t have running water. Deans drive students to get haircuts. Grandma keeps a pack of mini deodorants under her desk for when the boys get musty.

It’s a place where the principal takes care of bullet wounds.

Fama keeps her “doctor’s bag” — a Saks Fifth Avenue bag that carries a jumble of gauze and ointments — in her desk for when bandages need changed. She doesn’t have any medical training, so she tries to imitate what the wrapping looked like when she first saw it. She’s gotten pretty good.

“When I went to school, school was school,” Grandma says. “But this is everything.”

Phalen’s teachers and administrators have to be nurses, mental health experts, confidants and parents.

“You slide in academics — if you can,” Grandma says.

Da’Quincy’s mom is a nursing assistant, but she’d never taken care of a fresh gunshot wound until her son was full of them.

Shirley Collins, 38, has five sons, and she wants them to stay in the house.

“I really can’t trust the world,” she says. “I don’t want to let my kids out of my sight.”

But Da’Quincy has been asking to go back to school, and she thinks he’s ready.

Fama isn’t so sure. A Barack Obama campaign poster and a portrait of Michelle look down from the wall in her office as Da’Quincy explains that he left his arm brace and some of his medicine at home. His mom says he won’t take his vitamins or drink his Ensure. She says he doesn't like physical therapy because his therapist is a man who won’t let him get away with anything.

Grandma is back in the office, pears and carton of milk in hand. She’s beside herself. “You can’t lose ground!”

Months ago, Da’Quincy was a star wide receiver on the football team. He’s adamant that he’ll play again, anywhere that will let him, but the adults aren’t convinced. He might have to coach.

Now Fama and Grandma spoon-feed him applesauce. He doesn’t argue.

He wanders down the hall to his first class, escorted by a friend and looking a little dazed as he navigates a rush of handshakes and hugs.

He tries not to think about the shooting, but sometimes he can’t help it. It gnaws at him. It makes him look over his shoulder.

A girl runs up squealing and squeezes him too hard. A teacher chides, “Honey, don’t do that to him!”

In the hall, he runs into Mudder, who was shot just a month before he was. Mudder grins at him, the hard lump of a bullet still lodged between his eyes.

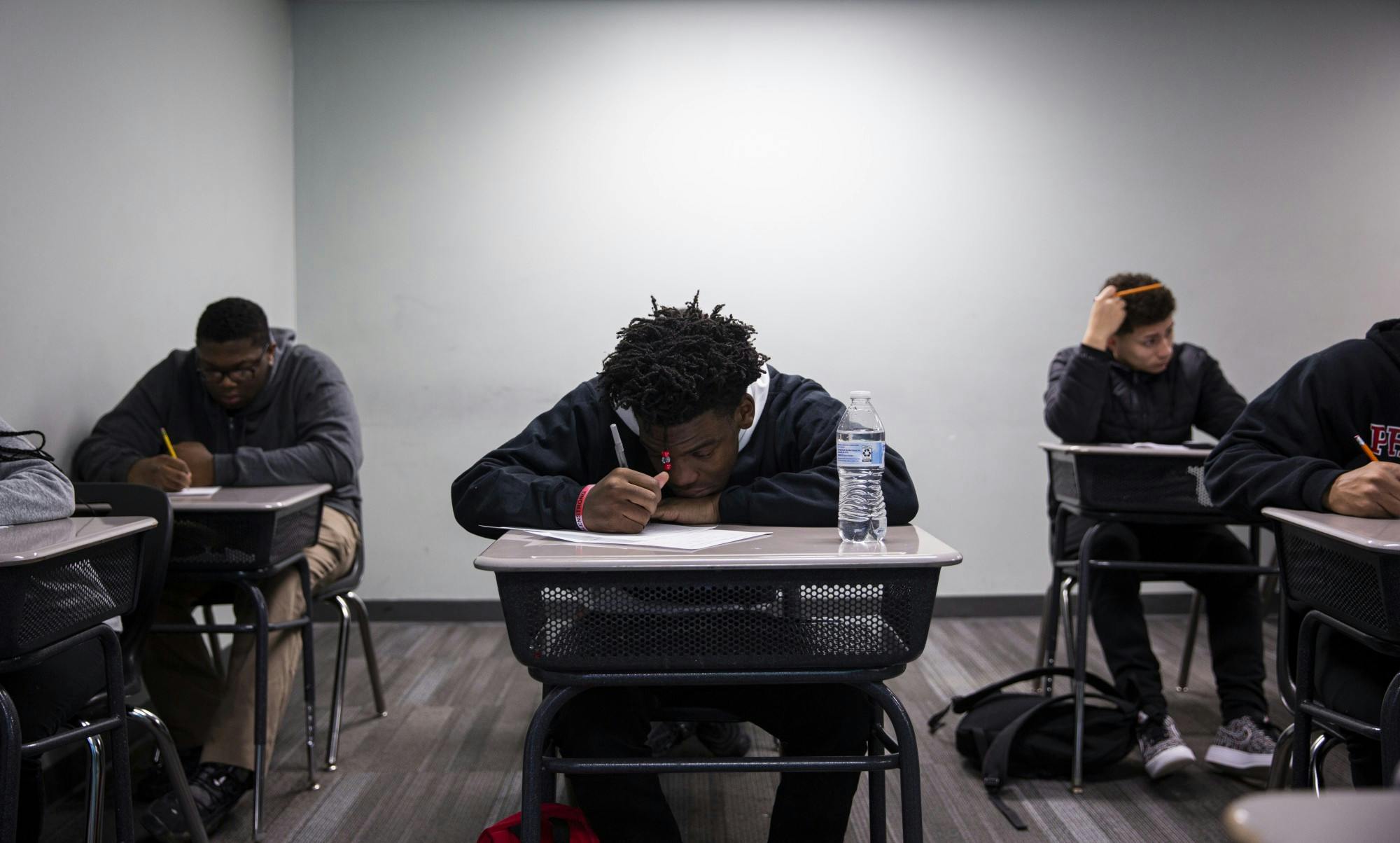

Hero’s welcome over, it’s time for geometry.

Almost every student at Phalen knows someone who’s been shot. They hear gunfire as often as thunder.

Taevion, 14, lives at Carriage House, an apartment complex about half a mile from the school, where four young adults were killed a few weeks ago. That night, she rolled out of bed and dropped to the ground.

She drops to the ground about three times a week. She rearranged her room a long time ago so her feet would face the window — so she wouldn’t be shot in the head.

When she hears gunshots, she texts everyone who lives around her “You cool?” or “You straight?” If they don’t respond, she knocks on their doors.

Rashad, 12, knows to turn off all the lights and TVs when he hears shots and hide in his room with his little sister.

When one boy on the basketball team heard gunshots, he lay on top of his grandmother to protect her. A group of students were shot at as they walked home from drama practice. A different group was shot at leaving a basketball game. One boy used to stay up all night because he was scared. He’d sleep at school.

Nevaeh’s mom was shot with an AK-47 when she was pregnant with her. And what does the 13-year-old think when she hears gunshots?

“I know somebody finna die. ‘Cause it’s the usual stuff.”

Mudder was riding in a car when he was shot. Da’Quincy was sitting in one. Another Phalen scholar was at a party. A fourth was in his dad’s front yard. The fifth was on his front porch.

"I keep screaming,” Fama says. “I'm waiting for people to be outraged, and no one is.”

When Mudder was shot on Thanksgiving Day, students started calling and texting her.

She rushed to the hospital and held his hand. The students looked at her like she should be able to fix it. To fix any of it.

“We feed them. We clothe them. We take them places. We pay for things for them,” she said later. “And so when something bad happens, you know, it's an instinct to run to your parents. I was in tears. I was like, ‘What did you think I could do?’

“I could do a lot, but I can't stop a bullet.”

Da’Quincy’s biggest fear was always being shot, but he didn’t think it would actually happen. He doesn’t like needles and couldn't imagine bullets.

He thought he would focus on football and school, and his life would be smooth. On the night of Dec. 29, he was sitting in a car with a friend, talking on the phone with some girls, when he saw three men walking up and felt something wasn’t right.

“Lock the doors,” he said, but the men were already climbing in. They demanded everything he had. He told them the truth: He didn’t have anything but his shoes.

“You think I’m playin’?” one asked.

They shot him six times. No one has been arrested.

Da’Quincy remembers a woman trying to get him to drink bottles of water as they waited for help. He remembers not knowing where the blood was coming from, but knowing his hoodie was drenched. He didn’t realize how many times he’d been hit until the paramedics cut his clothes off in the ambulance and he saw the holes.

When his mother saw him on the hospital bed, she passed out.

“I’m sorry,” he told her. “I’m sorry.”

He remembers being hooked up to all the machines. He remembers being calm. He thought of the bullet rooted in Mudder’s forehead. He remembers not crying.

“I swear to God, I didn’t think I was going to make it.”

He came to school a few weeks after the shooting because he wanted to talk to the football team. Before, he was an athlete. Sitting in front of them in his Pac-Man pajamas, he told them he couldn’t lift a spoon to his mouth. He couldn’t wipe himself.

He had a message for them.

“This ain’t what we need to go through,” he said. “Stay in the house where you safe.”

Phalen is supposed to expand to offer 11th grade next year, but that project is nearing a standstill. At least $1.2 million is needed just to open the doors in the fall.

One Monday afternoon, Fama launches into a series of tense meetings about how they’re going to make that happen. They have no idea.

“We’ve had our backs against the wall before,” Grandma reminds her. “We’ll just wait and see what happens.”

But Fama’s tired.

A dog park in Broad Ripple just got a $600,000 facelift. The City of Carmel took out loans to help fund a luxury hotel project that's now more than $18 million over budget.

Some kids at Phalen are going home to places where the lights being on isn’t a given. They’re begging for more after-school activities to stay where it’s safe for just a little while longer. But until the renovations are done, Phalen is out of space.

A boy came in earlier that morning and asked Fama’s dad, Coach, for something dry to wear. He had missed the bus and walked an hour to school so his mom wouldn’t whoop him. He was drenched. Coach dutifully put his clothes in the dryer and found him a sweatshirt.

Fama doesn’t have the $3.5 million she needs to build her scholars a gym, and she doesn’t know where she’s going to get it.

“You take better care of dogs than you do children on the east side,” she says. But she’s talking to herself.

Mr. Dwenger launches into his lesson on finding the volume of a sphere. Da’Quincy puts his head in his hands. The student sitting behind him answers every question. Da’Quincy plays with his shoelaces and picks at his lip. His foot, full of nerves still fried from when the bullet shattered his femur, is aching. An announcement over the loudspeaker reminds everyone tomorrow is school picture day.

Da’Quincy makes it 18 minutes into geometry.

He limps back to Fama’s office, calculator in his back pocket, and doesn’t stop to talk to anyone this time. He’s so irritated with how much his foot aches, he can’t think about anything else. He opens Fama’s door.

“Already, my sweetheart?” she asks.

He spends the rest of the morning with the nurse, lying with his knees tucked to his chest, knit blanket pulled over his head, curtain drawn around him. The signs on the wall tell him he’s brave and tough and important, and remind him to stay hydrated and wash his hands.

He tries to go to the bathroom, but he feels like his body is shutting down. He collapses to the floor.

He has to be helped back to bed, and he’s mad. He wants to be able to do things himself.

Da’Quincy knows he’s pushed it too far today, but he assures the nurse he feels OK now. She calls Mom anyway.

“It might just be too much for him to be here today,” she says quietly.

When Mom arrives, they settle Da’Quincy into a wheelchair and help him into her minivan. He promises he’s going to take his iron pills and be back tomorrow.

Sometimes he thinks people assume he's going to fall and crash. But he’s determined not to.

“I feel like they don’t understand that I want better than what most people expect,” he says.

He prays he’ll make it. He prays for better days. He trusts God’s plan for him.

This week, despite six gunshots, five surgeries and weeks spent relearning how to be a teenager, the boy who hates needles but is full of metal will turn 16.