John William’s protagonist, William Stoner, wasn’t esteemed in his work as an assistant professor or as an author. His marriage, his affair and his work relationships failed to bring him fulfillment either — in fact, they turned the screws of misery in his existence.

On page one, the reader sees Stoner had little impact on anything or anyone, and that his life was altogether insignificant, in the following passage:

“Stoner’s colleagues, who held him in no particular esteem when he was alive, speak of him rarely now; to the older ones, his name is a reminder of the end that awaits them all, and to the younger ones it is merely a sound which evokes no sense of the past and no identity with which they can associate themselves or their careers.”

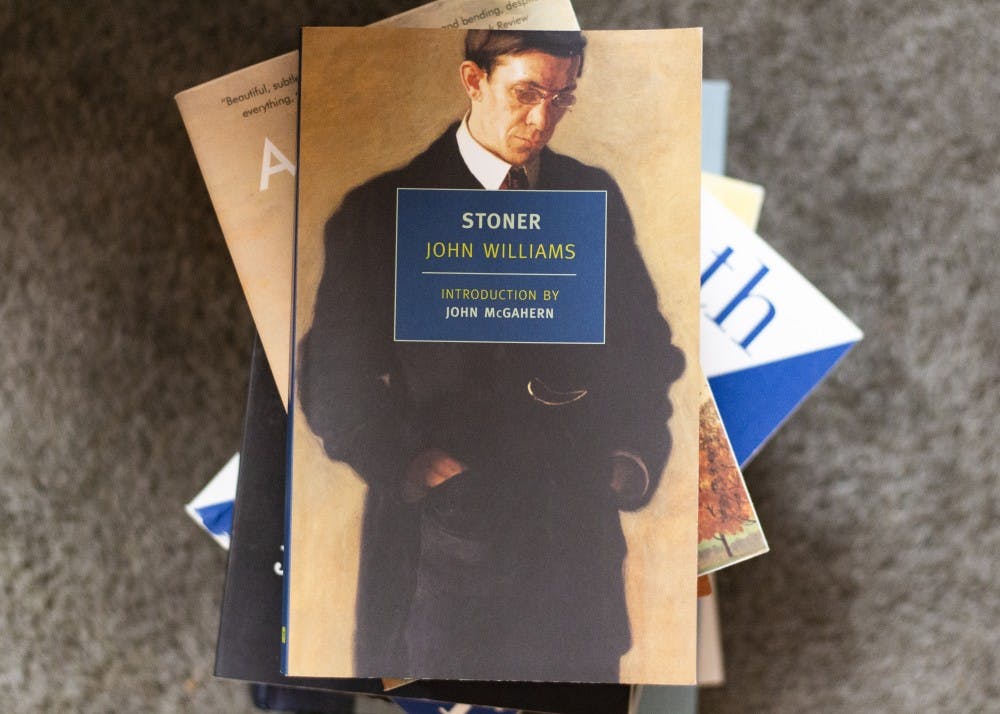

Written in 1965, “Stoner” follows the life of William Stoner, a farm boy turned academic, as he seeks to live and work through constant and bitter strife.

His miseries begin with his young and hasty marriage to Edith Bostwick. She is cold, indifferent and can barely stand the sight of him. She sees their marriage as an undesired obligation, a perspective Stoner quickly realizes in the following passage:

“Within a month he knew that his marriage was a failure; within a year he stopped hoping that it would improve.”

Edith is portrayed as vicious, cruel and hateful at times, and she grows sick at the sight of Stoner and is constantly jostling to make him miserable.

His battles don’t stop there — his colleague, the ruthless Professor Hollis Lomax — who in a questionable way is introduced and marked by pairing his villainy with physical deformity — does everything in his power to make Stoner’s work at the University of Missouri miserable. Two of Stoner’s only real friends, Dave Masters and Professor Archer Sloane, die early in Stoner’s life.

When they occur, the occasional snapshots of happiness in Stoner’s life stand out against an onslaught of aggression and hatred directed at him. Namely, when Stoner is sitting in his office with his young daughter, Grace, or experiencing his love affair with Katherine Driscoll, a graduate student at the university, beautifully explored in passages such as the following:

“William was shocked to discover his surprise when he learned that she had had a lover before him; he realized that he had started to think of themselves as never really having existed before they came together.”

His work as an assistant professor brings him joy, and the effort he puts into his academic research fills him with a feeling of direction he finds nowhere else in his life.

Despite the horrendous schedules and low-level classes Professor Lomax forces him to teach, and the spite and hatred Edith reserves for him, Stoner wears a face of indifference. In this way he takes on the stoic outlook of his parents, worn in their lifetimes on the farm.

“Their lives had been expended in cheerless labor, their wills broken, their intelligences numbed ... And they would become a meaningless part of that stubborn earth to which they had long ago given themselves.”

“Stoner” is beautifully written and masterfully-crafted. Williams is an author who understands not just characters, but real people. Even the villainous characters who oppose Stoner are full of emotional toil with understandable backgrounds.

On his deathbed and in a haze of pills and deteriorating health, Stoner regards his teaching and career with great indifference, neither proud or disappointed. His thoughts about his own failing body sum up the mindset that won his life against abundant loss, disappointment and misery:

“The flesh is strong, he thought; stronger than we imagine. It wants always to go on.”