While the IU Cinema, Buskirk-Chumley Theater and even the Starlite Drive-In give movie buffs the chance to explore film in Bloomington, the film archives stowed away in the basement of the Herman B Wells Library are often forgotten as film treasures.

The IU Libraries Moving Image Archive is one of the world’s largest educational film and video collections. It houses tens of thousands of items spanning nearly 80 years of film and television production. In addition to film and video, the archive also has a collection of film equipment. But the newest additions to its collections are 80,000 to 100,000 commercials and a shipment of old film equipment.

The Black Film Center/Archive, also in the basement of Wells, has been housing films about and by black people since 1981, according to its website. This semester, the archive is kicking off a whole new list of film screenings and events.

IU Libraries Moving Image Archive

Andy Uhrich, a film archivist, sat in the dark rewinding a tape of commercials, the long filmstrips sliding over a spinning disc. The sound was similar to record scratches.

Black-and-white images flashed across the screen, which then paused on a boy with a cardboard box. Uhrich took his hands off the table.

“As you know, there is a coin shortage,” the commercial’s narrator said.

“Wait, I didn’t know that,” Rachael Stoeltje, director of the IU Libraries Moving Image Archive, said.

Stoeltje said things like finding out when a coin shortage occurred are just some of the things researchers can glean from the archive’s new collection.

Temporary film archivist Katie Lind said the commercials can be used for research in almost any field, including gender studies, food policy, politics, film history, advertising and even economics, such as in the event of coin shortages.

The collection includes TV commercials that are entered to compete for the Clio Awards of the 1960s, '70s and '80s, which Stoeltje describes as the Oscars of advertising.

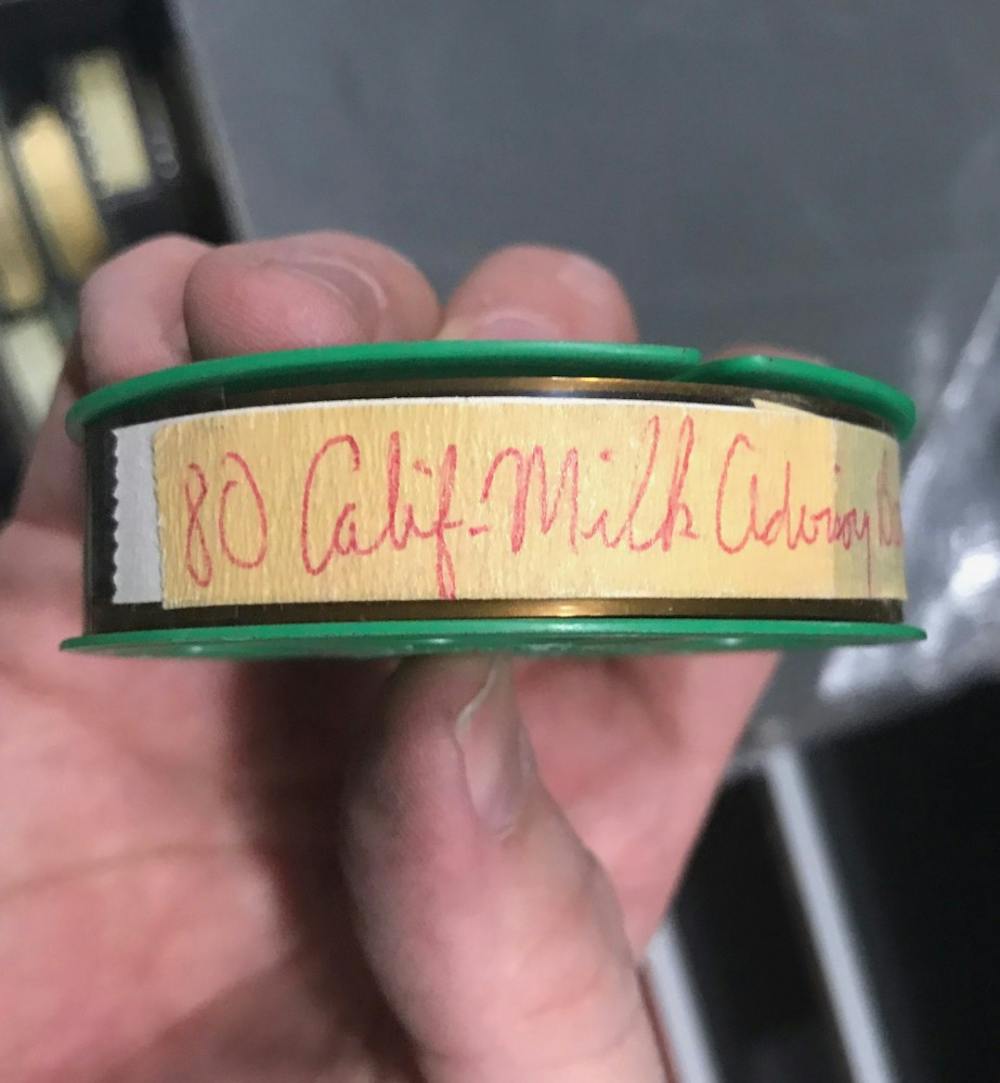

The reels are on 16 mm and 35 mm film and were stored in a New York City warehouse from 1992 until the London International Advertising Awards bought them and donated them to IU, according to a December 2017 press release from IU Newsroom.

“They were just sitting there unused, just piling up dust,” Stoeltje said.

Stoeltje said the University has digitized around 100 of the commercials, 45 of which are available for online streaming.

“This is really the library wanting all these commercials and resources to be available for research and scholarship,” Uhrich said. “We want it out there.”

Uhrich said digitizing these commercials is also a means of preserving the artifacts of human culture.

Another way of preserving culture is holding onto the equipment used to create cultural works, Uhrich said.

The archive is currently cleaning and storing 200 new cameras and 44 projectors donated by Washington, D.C. archivist Alan Lewis. Some of the equipment dates back to as far as the 1920s.

Stoeltje said the archive is trying to preserve the technology just as much as the images themselves.

Doing so means people can access old tapes sitting in their attics that can only be played on older projectors, she said. The equipment can open the locks to artifacts that would otherwise just collect dust.

Uhrich said keeping older equipment is part of understanding how society got to the point where video is everywhere.

“This is part of that story, our story,” he said.

Lind said some of her favorite commercials are the ones advertising processed meats.

“They were just very excited about their processed meats,” Lind said.

Stoeltje said the commercials are keys to explore the culture and values of the societies they were created in.

“There was this idea that they were cutting out all those pesky natural things to make something quicker, so it shows how our culture values the faster and easier,” Stoeltje said. “Now, the trend is to tout how natural something is, so it’s really come full circle.”

Urchi said a lot of more experimental, avant-garde film styles entered the mainstream through ads. As a result, commercials serve as a way to understand changes in styles through time.

“Ads could be a little more creative, a little more adventurous, a little more surrealistic than mainstream TV and movies,” he said. “Then they kind of bled over and influenced TV and film as well.”

Lind said the reels also include commercials from 85 countries. While she has not seen a lot of the international commercials yet, she said she enjoyed watching some of the ones from Japan.

Uhrich said the commercials are a treasure chest for learning about cultures around the world through time, but only time will tell how researchers and scholars will put them to use.

“The options are endless,” he said.

Black Film Center/Archive

Between film events, screenings and guest speakers, the Black Film Center/Archive on the ground floor of Wells provides diverse programming for the Bloomington film sphere.

“We’re here for the preservation, the conservation, of the creative film works from people of African descent around the world,” director Terri Francis said. “We’re here for things that are already known as culturally and historically significant, and also those that are not known to be culturally and historically significant.”

The center will screen the 1969 film “Change of Mind” on Feb. 23. The movie tells the story of a white district attorney having his brain transplanted into the skull of a black man and his new challenges involving a racially charged murder case.

“All of this is all based on people really feeling like black bodies and white bodies are very different and yet not different,” Francis said. “They really feel like they have a black brain, and that’s not how anything works.”

From February to April, the Black Film Center/Archive will present the Black Film: Nontheatrical series, a monthly screening and lecture series revolving around films that were never aired on theater screens.

The first archivist will be Candace Ming of the South Side Home Movie Project at the University of Chicago. The presentation will be Feb. 8 at IU Library screening room in Wells Library.

Ina Archer from the Smithsonian African American Museum of History and Culture will visit in March.

A collection of film from Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Company, housed at UCLA, will be presented by archivist Shani Miller in April.

“This African-American company based in LA took films of their picnics and their day-to-day work,” Francis said. “These are kind of corporate films. That preserves an incredibly rare history.”

By having these programs and keeping them safe and accessible, the central mission of preserving contemporary and historical film promotes education, Francis said.

“You’re really looking at a kind of space that’s, on the one hand, an oasis, a kind of soft space, a quiet space for contemplating and studying this history,” Francis said. “It’s also very much a battleground space that’s also protecting these materials from being forgotten, and really laying the foundation for filmmakers to build on that heritage.”