A dry smell of dead plants loomed in the air at the IU Herbarium.

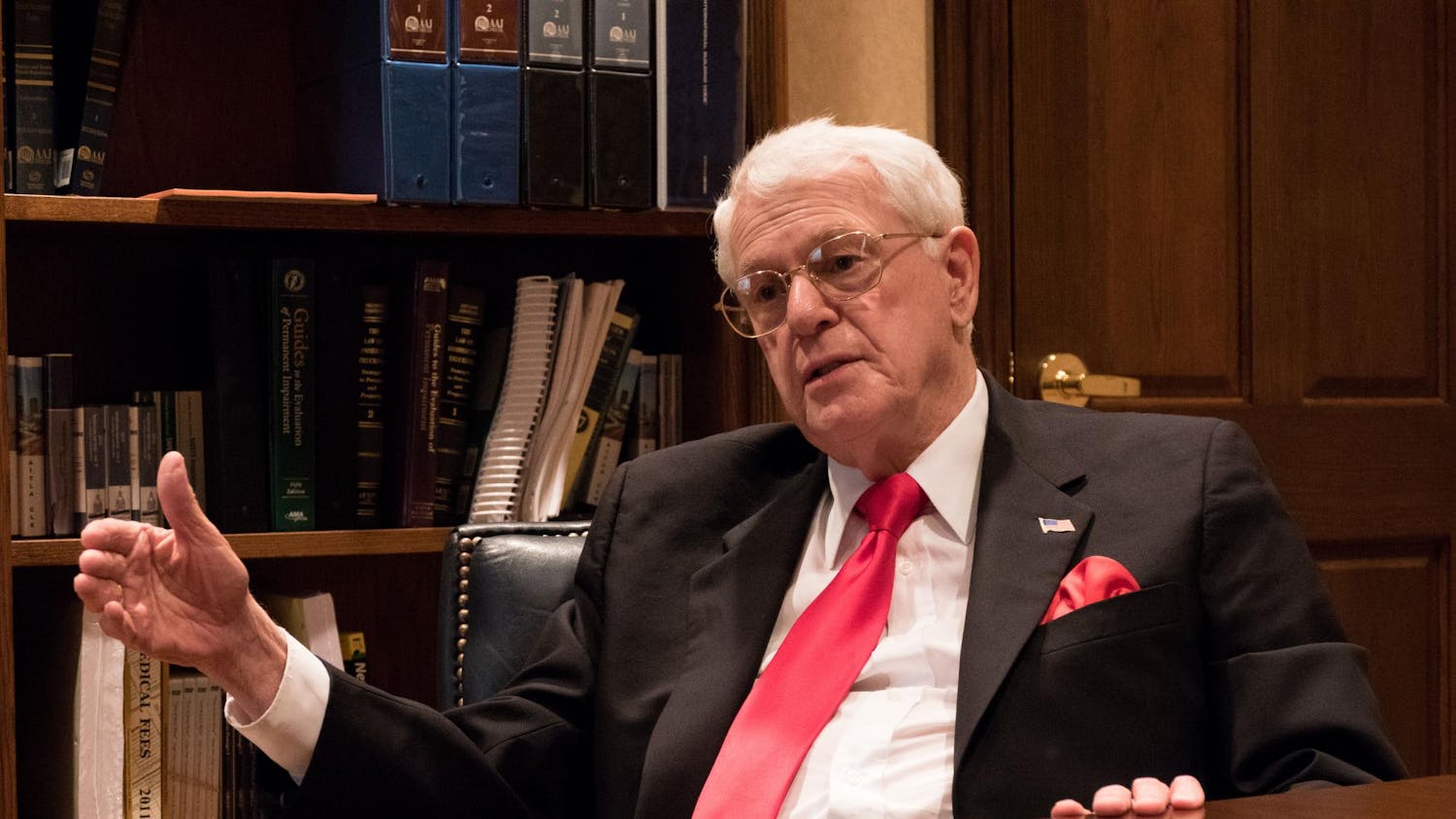

“People often call me to see how things at the herbarium are going,” said Eric Knox, senior scientist and director of the herbarium.

He chuckled. “I often say it’s pretty dead in here.”

Knox held a live plant in his hands and put it into a plant press to dry it out and to preserve it as a specimens for scientific research.

“Dead things are fun,” said Knox, sliding a plant into the plant press. “They are fun to look at and fun to study.”

Knox was having fun, but his work is also important, he said. These plant specimens allow Knox to help ecologists track changes of the flora in Indiana. Anyone can then look up this information online and find out key facts about flora in the state.

Knox is a professor who teaches Biol-B 300: Vascular Plants at IU. He got into the study of plants when his girlfriend from the University of Michigan told him to take a botany course because it was easy, he said.

Now he has his Ph.D. in botany.

“Sounds good to me,” he said. “Luckily, I really enjoyed that class and had an awesome professor who made plants sound really interesting.”

He spent more than ten years researching plants that grow on mountains in Africa, from northern Ethiopia to South Africa.

Now that he’s seen the world, Knox said he is focusing on expanding the herbarium’s database online so others can look into it and become interested in the world around them.

Knox and his student scientists are in the process of completely digitalizing the collection, which currently includes about 150,000 specimens. They are adding these specimens to the Consortium of Midwest Herbaria website, a database with plant information.

Knox helps the curators and student workers identify each specimen by characterizing its type of leaves, its ovaries and its color. Once they characterize the plant, they add a label describing the specimen to that plant’s portfolio.

Once the plant’s portfolio is complete with the label, Knox and a curator’s assistant photograph the individual portfolio and upload it onto the computer. When a plant’s information is visible online they can close the portfolio and put it into one of the large cabinets, according to the plant family it belongs to.

In the Smith Research Center, Knox and his student scientists come around to a man, Charles Deam, whom Knox calls his inspiration.

Deam, a botanist from Wells County, Indiana, had a collection of more than 70,000 plants. He gave his collection of plants to the University herbarium.

Knox pulled out a dusty copy of Deam’s book, “The Flora of Indiana,” which has all the species of specimens in every county of Indiana. Knox said he uses Deam’s book to classify the specimens he has left behind for them.

“Every plant that is collected is collected for a reason,” Knox said. “I want to have a love for nature like Charles.”

Knox may be inspired by Deam’s work, but the curator’s assistant at the herbarium, Tomás Fuentes-Rohwer said he looks up to Knox and aspires to have a passion like him.

Fuentes, 22, a curator’s assistant at the herbarium, is in charge of managing the collection. He is looking into creating an app so people can look up plants that they’re interested in.

“I want people to be as curious as professor Knox is about plants,” said Fuentes, holding a camera in one hand. “We have so much more plants that we need to preserve and find information about.”