A combination of stereotypes and biases influence the experiences of women in fields like science, technology, engineering and math (STEM), where they are generally underrepresented.

Maureen Biggers, the director of the Center of Excellence for Women in Technology at IU, said unconscious bias often plays a role in technology, where women make up a small percentage of the computing workforce.

For example, she has talked to women in technology whose ideas have been ignored in meetings, but when a man gave a similar idea later in the conversation, he was praised. Women are also interrupted more frequently than men, she said.

“Sometimes these things are so subtle that when you have it happen, even if you are not aware of it at a conscious level, it can impact how you feel whether you belong,” Biggers said.

Cate Taylor, assistant professor in sociology and gender studies, has conducted research on gender inequality and how it affects women’s experience in their occupations.

Her research looks into why both men and women are minorities in particular fields. For example, why are there so few female physicists? Why are male nurses so uncommon?

In general, implicit bias plays a major role in shaping societal expectations and gender stereotypes, she said. Common biases include the idea that women should do certain kinds of work and men should do other kinds of work, and the idea that women are better at certain occupations, while men are better at others.

“They often overlap, but both of them are biases and stereotypes that are pushing people into certain occupations, and keeping people out of certain occupations too,” Taylor said.

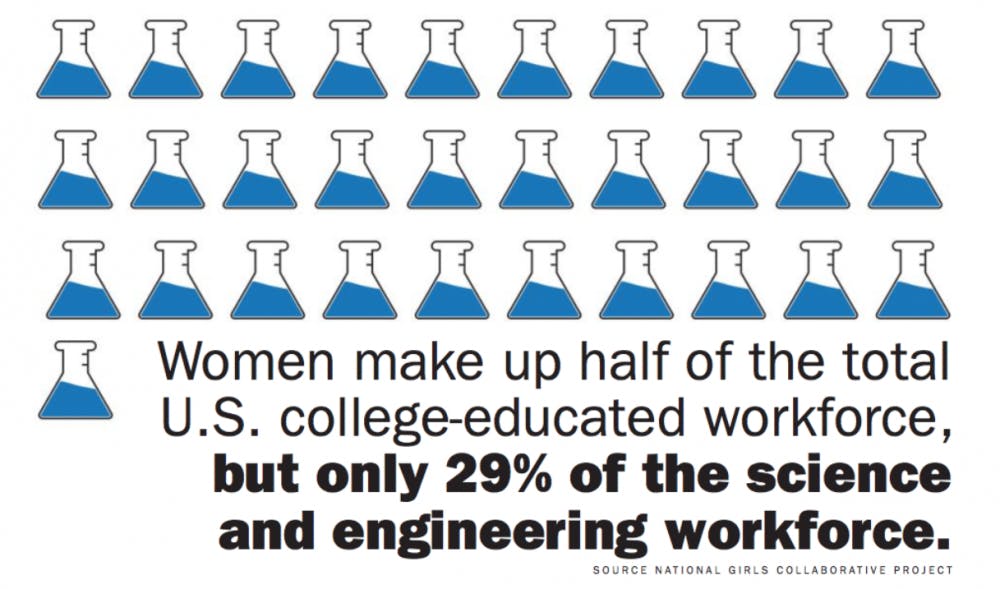

While women represent about half of the college-educated workforce in the U.S., they only make up 29 percent of the science and engineering workforce, according to the National Girls Collaborative Project.

Kayla Miller, a sixth-year PhD student in the Department of Biology and the founder of Indiana University Women in Science, said she does not feel like women are underrepresented in her graduate program, but the gender gap is usually reflected in higher positions such as faculty.

Although Miller does not face overt sexism, she said she has often encountered implicit bias.

“A lot of things are quiet, like ‘did they say that because I’m a woman,’ or ‘did they not give me that responsibility because I’m a woman,’ or ‘did they not let me do this opportunity because I’m a woman?’” Miller said. “It’s really hard to prove whether that’s really harassment or discrimination, but it sure as hell feels like it.”

Some of the stereotypes she has encountered include the idea that women cannot do everything that men can, or that women cannot handle the tough atmosphere.

It is difficult to get rid of implicit biases, she said, but one way to improve the situation is by creating opportunities for more female mentors and role models, especially in higher level jobs.

Women often hold themselves to higher standards, Biggers said, and if they fail to meet these standards, they might not feel like they belong. It is limiting to have the mindset that “you either have it or you don’t,” she said.

Taylor said her research contradicts several inaccurate ideas about why there is a gender gap in the workforce. For example, there is the belief that women simply prefer different kinds of jobs than men because male-dominated occupations are more stressful.

Research in psychology and sociology has shown that women in male-dominated occupations face more stress than men in the same occupation.

Her studies have involved placing women and men in the same stressful conditions, and she has observed that there is no difference when the situations are equal.

However, the combinations of the usual workplace stressors with other factors like implicit bias, sexual harassment or childcare responsibilities at home result in higher stress levels for women.

Male dominated jobs are often better jobs in terms of pay and benefits, Taylor said, and she encourages women to pursue these occupations.

In addition to implicit bias, another issue influencing gender inequality in occupations is how women are expected to put greater effort into childcare and housework than men, Taylor said.

“It doesn’t have to be that way—like it’s just the way our culture is right now—but it’s empirically true,” she said.

Women who do not prioritize family over work are often seen as bad mothers, she said, but there is a different set of expectations for men. Men are often praised as great fathers for even minimal involvement in childcare, she said.

Paid work also makes it difficult for gender inequality in the workplace, because it generally is not structured to accommodate for childcare or housework, so many couples often have to choose who is going to prioritize work, she said. This often ends up being the men, since they tend to have the higher paying jobs.

“Those choices have to be understood within the constraint of a culture that pays men a lot and gives men better work,” she said. “It’s sort of, quote on quote, rational for families to make that choice, but it’s only because we’ve set up our culture in a way that privileges men’s paid work.”

Tanya Cheeke, a post-doctoral fellow in microbiology, said she hasn’t had many female role models in her field whom have also been married with children.

Many men do not seem to be making the choice between their careers and having a family because of their support systems at home, she said, but women seem more likely to make these choices.

However, Cheeke said she has a support network that has allowed her to have both a family and a career in science.

She is a mother of a two-year-old daughter, and her partner is a stay-at-home dad. It has been helpful to have someone who can take care of childcare and housework while she is working, she said.

She originally thought it would be difficult to balance family and her career, but she has discovered that it is not as difficult as she expected.

“It’s really not so bad, and I wish I had known that earlier,” Cheeke said. “I thought it was going to be this major life change. I’m very lucky to have this stay-at-home person who helps with the day to day.”

Improvements need to be made both on an organizational and individual level, Taylor said. To close the gender gap, it is important for organizations to both pay men and women equally and give them equal benefits.

Having clear, specific criteria for hiring and pay is also important, she said.

“Implicit biases are much more prevalent in contexts where there’s a lot of uncertainty,” Taylor said.

Individuals can improve the situation simply by becoming more educated on implicit biases, she said. One small thing people can do is give credit to women when they offer a suggestion or idea.

There are many advantages to diversity in academics and the workforce, Biggers said.

“Research shows that the best performing teams that produce the best products are diverse and have women and people of color on them,” she said.