The Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 is up for its five-year review. Indiana’s food service workers have a few changes in mind to make better-tasting food.

The act, which has been in place since 2012, mandates low sodium and 100 percent whole grains and has caused headaches for Monroe County School Corporation employees such as Johnson. She’s responsible for ensuring more than 11,000 students are fed according to Department of Agriculture regulations.

Abiding by these laws has made the past three years challenging, she said. While she acknowledged some of the changes are “common sense,” Johnson said a few alterations are necessary.

“There are some things I think are personally over the top,” she said. “I think it does warrant some tweaking.”

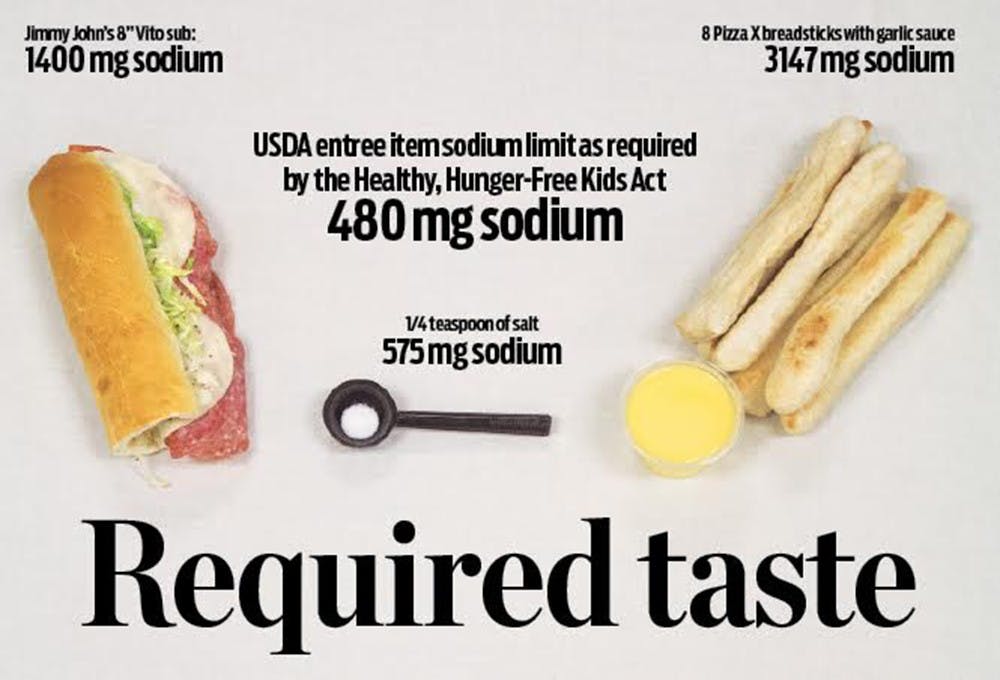

The act also mandates sugar cuts, more guarded calorie intake by grade level and a fruit or vegetable on every plate. Johnson said the portion sizes are adequate, but both she and Lindsey Hill, director of nutrition services at South Madison Community School Corporation, said sodium reductions have cut out flavor.

“Some things naturally have sodium in it. That’s where your flavor is going to come from,” Johnson said.

Under the Act, schools are required to move to even lower salt levels as time goes on. Hill called that unrealistic.

“It would be nearly impossible to meet these numbers,” Hill said, adding that they don’t align with science. Johnson said some salt-stripped foods are lacking, causing kids to avoid them. If further cuts are made, she said, “everything’s going to be totally flavorless.”

Hill said if it were up to her, sodium levels would stay put, and schools would be required to serve 50 percent whole grain products rather than 100 percent. That rule reduced the options school cafeterias had and made it harder for them to serve food kids want to eat. Few products that met the standards were available in mass quantities from manufacturers and quality suffered, she said.

“(Manufacturers) rushed to make products that were compliant, and they’re not the best possible,” she said.

Kay Sayles, the kitchen manager at Fairview Elementary School, said she wants to give kids the best food possible. It hurts when she sees them throwing away what she serves she said. About 90 percent of Fairview students qualify for free or reduced lunch, and Sayles said for some of them, this might be the last meal of the day they receive.

“You want to see the kids eat,” she said. “They depend on us to feed them, and this is the place that they know they’re going to get fed. It’s kind of hard to see them come here and not enjoy their lunch like they used to.”

The pasta is mushier now, Sayles said, and kids don’t like it anymore. Johnson said the whole grain cookies aren’t as popular, either. Kids aren’t happy about the potatoes.

“The mashed potatoes are really struggling,” Johnson said.

Families across the U.S. deal with food insecurity. Many can’t afford to pay the full price of a daily meal — that’s where free and reduced lunch options come in.

Almost all public schools in the U.S. are part of the federally-funded National School Lunch Program, which allows them to serve free or reduced-price lunches to kids who qualify. The USDA reimburses schools for every meal, so they end up with the same income — but that meal must be considered balanced. So, for children to receive a free lunch, they must fill their trays with a certain combination of items — including a fruit or vegetable.

Despite challenges caused by the act, both Sayles and Johnson agreed it has made lunches healthier. A 2015 study by the University of Connecticut reported kids were throwing away less of their meals, and a study by the Harvard School of Public Health reported in 2014 kids were eating 16 percent more vegetables and 23 percent more fruit at lunch.

Johnson called the meals she serves well-balanced.

“I think it’s pretty good,” she said. “I think we have good lunches.”

Charlotte Fenstermaker, a sixth-grader at Fairview Elementary, said she likes eating lunch at school. She said she thinks it’s healthy, but her cousin, fellow sixth-grader Nicholas Houshour, said the food isn’t always good — it depends on what the kitchen serves. But Fenstermaker didn’t have any complaints about the food — in fact, the whole grain spaghetti is one of her favorite meals. Her only suggestion to the kitchen is to serve slushies every day.

Both students said they eat their vegetables and always clear their plates.

Sayles said while she has noticed kids eating more fresh fruits and vegetables, she’s also seen more food going into the trash.

“It breaks my heart, because you don’t want to waste food,” she said. “A lot of people, particularly children, they go hungry.”

Sayles, Hill and Johnson agreed that Congress should lift the strict 100 percent whole grain requirement, and keep sodium levels where they are.

“I would jump for joy if they said you don’t have to drop sodium anymore,” Sayles said.