All these years later, he remembers the chills that crawled down his spine each time he stepped onto the court.

He can still see the gymnasium lights beaming overhead. He hears the chant of the crowd booming from the bleachers. Whenever he played, his worries vanished and his mind honed to the thump of the basketball. On the court, he was home.

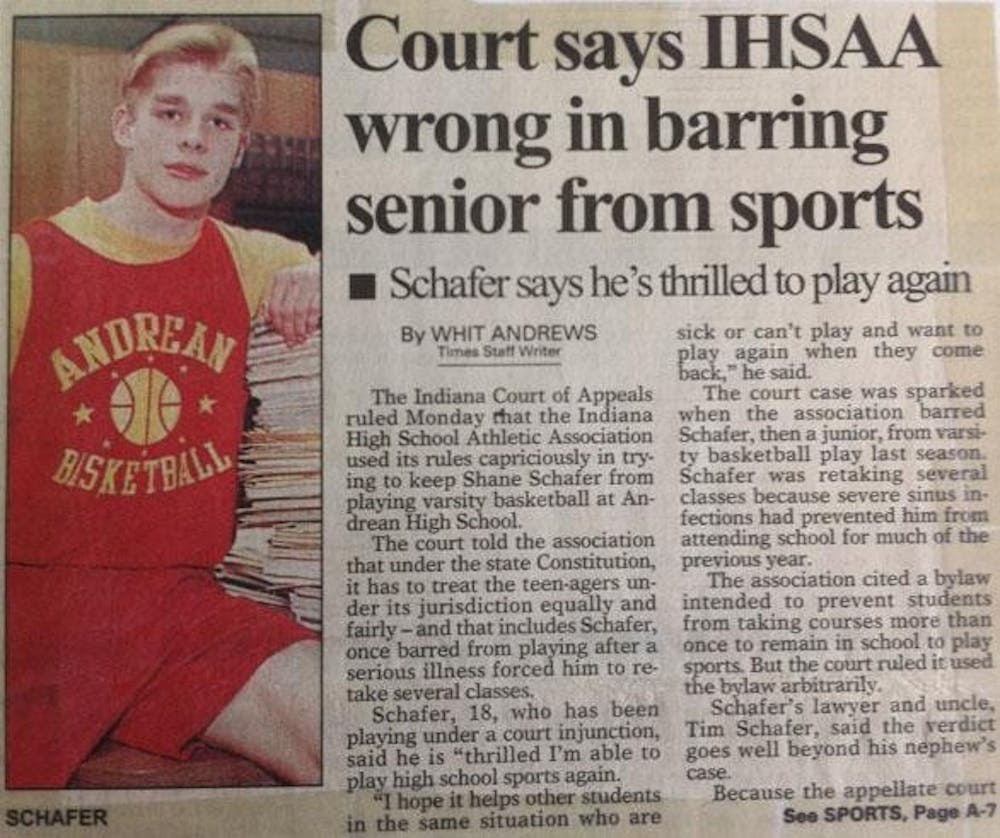

No. 22 Shane Schafer, then 16, often played guard. He wasn’t the best. It was a fight to earn his spot on the powerhouse team at Andrean High School in Merrillville, Ind. But it was all he wanted.

That passion was sidelined when sickness shelved his junior-year season.

When he asked the Indiana High School Athletic Association for that time back, they said no. When Schafer filed suit and the judge allowed him to play, the IHSAA countered with another rule to keep him off the court.

As judge after judge sided with the Schafers, the IHSAA filed appeal after appeal to justify its exercise of power and maintain they were in the right. For 22 years, the legal case dragged on, like an overtime that wouldn’t end.

“They couldn’t admit they were wrong,” Schafer said, now 39-years-old. “They couldn’t let go. They had to fight ’til the bitter end.”

Today, after another ruling in December, the court battle is nearing a resolution.

* * *

The court to court saga has been a battle of wills and endurance. It stands as the longest legal battle the IHSAA has ever fought.

A series of judges railed against the governing body through the years. Early courts found the way the IHSAA applied its rules to Schafer to be “arbitrary and capricious.” It characterized the IHSAA’s decades-long defense as “frivolous, unreasonable, and groundless.” Multiple court opinions questioned the IHSAA’s motives, wondering aloud if its tactics were meant to intimidate challengers to its power.

C. Eugene Cato, then the association’s commissioner, was asked in court why the IHSAA insisted on fighting the case.

“I don’t know why,” he said.

The love of the game, the beating heart of small towns across the Hoosier nation, was threatened by the very organization entrusted to “encourage and direct wholesome amateur athletics in the high schools of Indiana.”

The power play shadowed Shane Schafer as he graduated from Andrean, then through his college years, his wedding and the birth of his two daughters.

Though he admits the case made him bitter, his memories of playing still bring a smile to his face.

Earning a spot on the Andrean High School basketball team was a matter of pride, and it became part of Schafer's high school identity. Teammates became best friends. They hung out outside of practice. Before games, the friends would eat dinner at Schafer’s house. They felt the pulse of early 1990s rap in the locker room as they readied themselves to play.

“The fulfillment of just being with that team,” Schafer said, “was just greater than anything else for me.”

He worked his way to the varsity team his junior year. He was positioned for a successful senior year, and who knew, maybe college play?

As winter hit, so did chronic sinus pain that eventually forced Schafer off the court, away from school and into the hospital for surgery. The recovery was complicated and lengthy. Schafer missed so much school that Andrean allowed him to re-do his junior year.

When he wrote to the IHSAA to ask for another year on the court, the governing body refused. IHSAA rules prevent students from playing more than eight consecutive semesters.

Again the family appealed. Again, the IHSAA said Schafer was ineligible for the year in question. But this time the organization cited another rule that banned him from half of the only year he had left.

The IHSAA’s refusal sparked Shane’s uncle, attorney Timothy Schafer, to step in and file suit. They took the case to a Lake County Superior Court in November 1991.

“I felt that because we chose to appeal that first ruling, they were going to show me,” Shane Schafer said. “They were going to find a rule to apply to me to knock me down even further.”

The Lake Superior Court ruled that Schafer “appears to be entitled to take part in athletic competition” during the second semester of his junior year, according to court documents.

Teammates, coaches and family rallied around Schafer. He even received an encouraging handwritten letter from a former coach.

“It was inspiring for me to keep up the fight,” Schafer said.

At the request of the IHSAA, the case was moved to the Jasper Circuit Court, where Judge Raymond Kickbush ruled on the case in January 1992. He concluded IHSAA rules were “overly broad, overly inclusive, arbitrary, and capricious and do not bear a fair relationship to the intended purpose of the rules ...”

The same court characterized the IHSAA’s defense as frivolous, unreasonable and groundless.

The court system eventually allowed Schafer to take to play that month, almost one year after the sinus problems benched him.

He still remembers that first time back on the basketball court. Teammates drowned him in a sea of high-fives as he made his way through the locker room. As the second quarter neared its end, Schafer hit a half-court shot.

“I felt like I could be me again,” Schafer said. “I felt like I was in high school again.”

The IHSAA tried again to bar Schafer from playing — this time during the 1992-93 school year — appealing up to the Indiana Supreme Court, which chose to not hear the case.

Schafer would be allowed to play his senior year, though he fell and broke his hand midway through that season, dashing his dreams of senior year glory.

And though Schafer was again off the court, the legal fees absorbed by Shane’s uncle had grown to the tens of thousands. The Schafers requested a hearing, wanting the IHSAA to foot the bill.

More courts would see the case concerning legal fees and its appeals for years to come. Schafer had no idea the final ruling on those damages was still 20 years away.

* * *

For the Schafers, basketball is a family affair.

Shane's Uncle Timothy, the lawyer, played on IU’s freshman team back when there was more than just the single collegiate team. His younger cousins and brother played the sport, too. Cousin Todd Schafer was the state’s leading scorer in high school basketball during the 2002-03 season.

Schafer started sports young. The number 22 has covered his chest since he was 12-years-old. He chose to focus on basketball in high school, and eventually worked his way onto the highly competitive varsity team.

Former Andrean Coach Bob Buscher remembers coaching Schafer, as he remembers many of the hundreds of students he has coached in his 36 years.

“He was a hard worker," Buscher said. "He did what I asked him to do. He was coachable on the court.”

Andrean, a Catholic high school, attracted some of the best talent from the region. Students planned their Friday and Saturday nights around basketball games, which often drew a full house that always included Schafer’s parents.

A certain aura surrounded the season.

“It’s Indiana basketball,” Schafer said. "It’s a brotherhood.”

* * *

Even now, two decades later, Schafer can’t explain why the IHSAA continued its fight against him.

Current IHSAA Commissioner Bobby Cox inherited the case from past commissioners. In a recent interview, he said the motive behind the decades of appeals was not the question of Schafer’s eligibility. Rules were rules.

“When we make decisions,” Cox said, “we have a duty and an obligation to uphold our rules.”

And as a private organization with a voluntary membership, Cox pointed out, the IHSAA had every right to appeal for as long as it did.

Schafer’s case about legal fees made its way through a few different judges and courts before a special judge ordered the IHSAA to pay $86,231 to the family in 2003.

The IHSAA appealed the ruling, and in 2009 that appeal was denied.

Schafer’s uncle kept him in the loop with each new legal motion. Schafer’s cousins — pre-teens when the case began — worked on the case in recent years as members of the family law firm.

“It just didn’t make sense that they would spend all that money and resources to file appeal after appeal,” Shane Schafer said.

The IHSAA appealed yet again. Then, on December 17, Randall Shepard — former chief justice on the Indiana Supreme Court — handed down a ruling for the Court of Appeals.

“We are not the first appellate court to take notice of the IHSAA’s arbitrary and capricious decision-making toward the Schafers,” Shepard wrote. “Such decision-making can result in substantial harm to the individual student-athletes the rules are intended to serve.”

The court sided with the Schafers and again ordered the IHSAA to pay the family — this time $139,663.

Finally, the case that wouldn’t end appeared to be wrapping up, though the IHSAA still had the option to appeal to the Indiana Supreme Court.

The case, Schafer holds, was a power struggle all along.

In 1992 Judge Kickbush in the Jasper Circuit Court said the IHSAA’s conduct in the litigation “degenerated to a goal to determine who would own the ship and who would paddle the oars.”

A September 2009 trial court opinion disapproved of the IHSAA tactics used in Schafer’s and other court cases, including suggestions that the organization was motivated to run up fees and expenses to warn parents and students against challenging a ruling.

In the most recent ruling in December 2013, Shepard's opinion cited another suit brought against the IHSAA. He noted, “The importance of this case...lies in the fact that students learn at the hands of the IHSAA some of their early lessons about what constitutes fair play in decision-making.

"Unfortunately, students acquainted with the IHSAA’s conduct in this case might reasonably conclude that winning at all costs is more important than fair play.”

Though not immediately sure after the December ruling, the IHSAA has decided it will not appeal the case to the Indiana Supreme Court, said current Commissioner Bobby Cox.

“We fought that fight, and now that fight’s in my lap, and I’ve determined it’s time to end this fight,” Cox said. “It’s time to move on with life.”

* * *

Schafer's two daughters, 4 and 7, don’t know about the case. And that’s how their father likes it. If they choose to play sports, he said, he wants them free of the burden and the fear he had in school.

Schafer now lives in Valparaiso, just across the lake from his uncle Timothy. He has worked at the Porter County Adult Probation Office since he graduated from Ball State University and now serves as a probation officer.

He often thinks about the decades his family has poured into the case. He knows most families wouldn’t have been able to continue a defense against the IHSAA.

“They’ve done this to other kids in the region,” Schafer said. “I’m just lucky I had an uncle that’s a lawyer. Their families can’t afford the type of legal bills this type of thing would cost.”

Why did they so feverishly pursue his case?

He’ll never have an answer.

“You sit here and think, 'Jeez, they could at least write an apology letter.'”

He’ll always wonder, what if? What if he had played for all of his junior year?

What if his family had never been burdened by the case?

He escapes these questions on the basketball court, a place he hopes to frequent until his body tells him otherwise.

Schafer has kept up his skills, playing regularly since his high school days.

“I choose to play when I want to play,” he said, “and no one can tell me when I can’t.”

He and his cousins find time for H-O-R-S-E and two-on-two in the backyard. At the Wheeler High School Field House in Valparaiso, Schafer dons his No. 22 jersey to compete in a weekend league and play pick-up games on weekdays.

Even on vacations, after the children are asleep and the wife is relaxing, Schafer ventures out to find a court.

The crowds are gone. The cheering exists now only in memory. But he still thirsts for the win.

Stepping on the court, the old instincts take over. Beads of sweat form along his forehead. His heartbeat quickens.

Dribbling the ball, he looks for his next move. Is the lane clear? Is there enough space to shoot the three? The glance toward the net. The shot.

He watches and waits.

This story was based on court documents and interviews with Shane Schafer, Timothy Schafer, Commissioner Bobby Cox and Schafer's former coach Bob Buscher.

Follow reporter Matthew Glowicki on Twitter @mattglo.

Court to Court

Decades-long power play ends in settlement

Get stories like this in your inbox

Subscribe