Last week, the organic food market went transcontinental.

On Feb. 15, the United States Department of Agriculture announced a new partnership between the U.S. and the European Union that would make the exchange of organic food products possible and affordable for both.

Starting June 1, organic products certified in the U.S. or the E.U. can be sold in both markets. Currently, the U.S. and E.U. have their own sets of regulations for certifying food as organic. The new partnership makes these regulations universal in both.

“What they did is called harmonization,” said Corinne Alexander, associate professor of agricultural economics at Purdue University. “Policy experts and trade folk say that regulations create a barrier to trade, so any time you harmonize those regulations and make them equivalent, you increase the amount of trade.”

The importance of these regulations for grocery store chains, such as Kroger or Walmart, is not yet known.

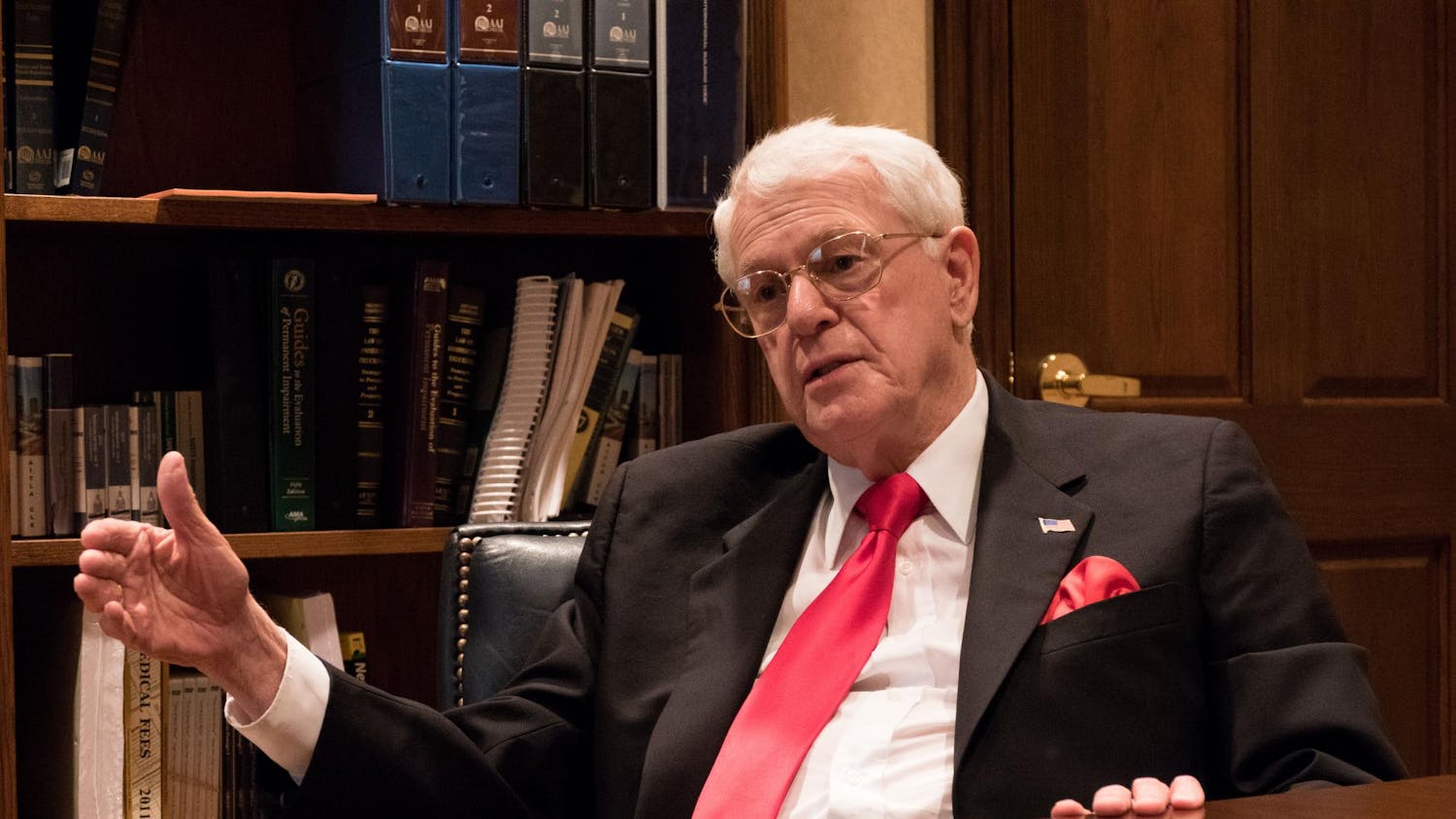

“To negotiate a deal around any product that has additional levels of regulation is really complicated and, in general, takes much longer,” said John Elliott, Kroger Central Division public affairs manager and spokesperson. Elliott is a former U.S. diplomat who focused on economic and trade policy in Asia.

“Any time you can have common standards, you ease and condense trade,” he said.

Elliott declined to reveal how these new regulations might change market prices in Kroger stores across the country but said the regulations will increase the variety and availability in the market as a whole. Kroger has a sizable organic product selection, and Elliott said the company strives to buy local when it can.

“We are a leader in the industry for local sourcing,” he said. “As much as we can, we buy local. It reduces cost for the customer. As part of our green sustainability policies, the closer we can buy to the consumer, the less fuel we use to transport the product.”

Elliott said for Kroger and other large companies, it’s not always the source of the product but the way it is marketed among competitors.

“If we can’t bring a product in from Spain or France now because of regulations, we can just bring it in from Guatemala or Chile,” he said. “This would just go into that same mix for additional opportunities for our staff to assess and compare market prices.”

Alexander said the companies growing in Mexico or Guatemala — companies that produce organic products on a large scale — will benefit most from these regulations.

“We’re in a world right now where there is a strong, persistent demand for organic products,” she said. “And there is a larger demand than U.S. producers can make.”

She said states such as California, Florida and Michigan will be able to open export markets in the E.U., benefiting most from their large, food-based industries.

But Indiana isn’t so lucky.

“We don’t have very many organic farmers in Indiana,” she said. “The majority of them are small-scale and are selling directly to Indiana customers.”

This means the new universal regulations won’t significantly change locally owned, private organic food stores one way or another, she said.

“The small-scale organic farmer that is selling locally is not just selling an organic product but also a product that is locally produced,” she said. “There is that consumer that wants to buy organic because it is locally grown, and they are going to be loyal to the local community. There is a niche. Local is the one thing that can’t be taken away from these regulations.”

Organic dairy farmers in Indiana could benefit from these regulations, especially since the only stipulation involves the use of antibiotics on organic animals. In the E.U., farmers are allowed to treat illnesses with antibiotics; in the U.S., they are not. U.S. dairy farmers can still export to the E.U., even though E.U. farmers who use antibiotics cannot reciprocate.

The U.S. and E.U. organic markets are valued at more than $50 billion combined. Organic exports reached approximately $1.8 billion in 2010, and the USDA predicts that number will grow 8 percent annually in upcoming years.

But Alexander said it takes a company three years to transition to become a certified organic food distributor, so it could take as long as five years before the market shows any significant changes.

Organic trade expands to European Union

Department of Agriculture announced a new partnership between U.S., EU

Get stories like this in your inbox

Subscribe