Joe is a boy. Sally is a girl. Joe has XY chromosomes. Sally has XX chromosomes.

But it’s not always that cut-and-dried.

The American Journal of Human Genetics reported a woman born with XY chromosomes who has completely normal female features and reproductive ability.

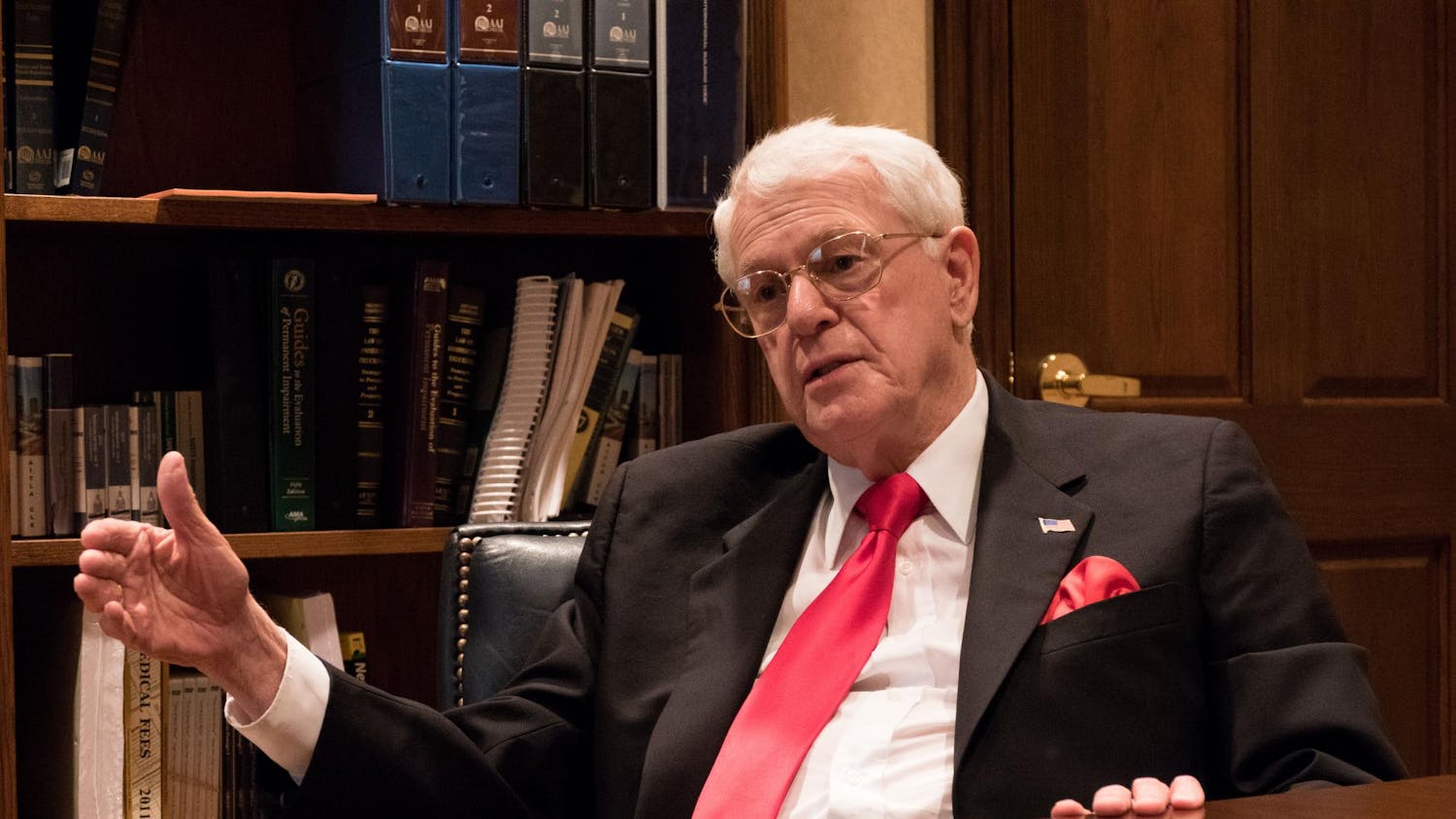

“People are taught in high school that people are XX or XY, and that’s not necessarily the case,” GLBT activist and senior Jain Waldrip said. “There are a lot of different combinations that can happen, and sometimes they happen without any physical symptoms to show that there is a different combination of sex chromosomes.”

From the first picture books read to us by our parents, gender roles are simplified into two categories. However, new studies show that this isn’t always the case.

For some people, the body they are born into doesn’t necessarily portray the gender that they identify with.

Transgender people are individuals whose gender identity, expression or behavior is different from those typical to their sex determined at birth.

“When I was 19, in college, I had already realized to myself what the problem was,” Waldrip said. “And it’s hard to admit to yourself because the question are you a boy or are you a girl is a very basic one that you’re taught is supposed to be solved by anatomy.”

Waldrip was male assigned at birth, but grew to realize that her physical entrapment did not reflect her inner identity.

What ensued was years of emotional chaos and turmoil and battles with depression that forced her to remove herself from collegiate study.

“It was incredibly frustrating and incredibly painful because I felt like my body was continuing in the mode of being that was hurtful to me,” Waldrip said. “I felt like now that I had identified the source of pain, all I could think about was finding a way for it to stop.”

Undergoing a gender transition is a long and difficult process for most individuals. Waldrip had to support herself out-of-pocket to afford proper therapy and medical treatment.

The standards of care for undergoing a gender transition are set by the Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association. They consist of a five-step process: diagnostic assessment, psychotherapy, real life experience, hormonal therapy and surgical therapy.

“In my case, it was really a response to pain," Waldrip said. "I was depressed, and honestly, I was suicidal since I was about 8 years old, and that was from some environmental factors and other internal things, like my discomfort in my body and in my social role that just wouldn’t go away.”

After eight months of therapy with Katy Koonce, a Texas therapist specializing in transgender assistance, Waldrip was authorized to begin medical treatment.

In 2006, Waldrip returned to school, attending IU-Purdue University Indianapolis. In 2008, she transferred to IU-Bloomington.

On her application, she was asked to explain her hiatus and what lead her to believe she could be more successful upon her return.

She wrote that she had been coping with her transition and battling depression and suicidal tendencies.

“I was amazed — there was absolutely no problem with that,” Waldrip said. “There was a good response, and I was accepted. I guess you wouldn’t think of that as a big thing, but it was a really touching moment for me and an indication that things had already started to change in that short period of time that I had been away from college.”

At IU, Waldrip has become an active member of the community, serving as the vice president of the Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Equality organization, or SAGE, and copy editing for the Indiana Daily Student.

“SAGE’s focus is really specifically on building community and building awareness,” Waldrip said. “We really want people to be prepared to get out into the real world and be the next generation of LGBT activists.”

For Waldrip, being well versed in the issues facing the GLBT community is of the utmost importance. Fighting for civil rights issues such as the Employment Non-Discrimination Act is extremely close to home.

Waldrip lost her job during her transition and continues to face hardships attempting to obtain equal employment rights.

“I feel that it’s a little unfortunate that GLBT people will be forced into an activist’s role,” Waldrip said. “I would rather that people choose that. But as we are still a minority and as there is still quite a lot of prejudice against us, I think it’s kind of necessary for people to at least be politically aware, if not politically active.”

Many individuals outside of the GLBT community aren’t regularly exposed to transpeople, resulting in a “fear of the unknown” attitude and a strain on intellectual dialogue.

“There’s this sort of general dislike of things that aren’t understood, and there are obviously a lot of negative stereotypes associated with transpeople and a lot of distrust of transpeople because we are seen as different on a fundamental level,” Waldrip said.

There is also the issue of the success of transitions, the goal being to live as one’s true gender identity.

An unknowing stranger would ideally have no idea that a transperson had been assigned an alternate gender at birth.

“People who don’t get perceived as their birth sex very often tend to not want to talk about their experiences as a transperson because that exposes them to a form of discrimination they are usually able to avoid,” Waldrip said. “There’s a lot of threats, and there’s a lot of potential for violence against transpeople.”

The deconstruction of gender roles has become more prominent in American society, as reflected in politics and social norms.

“I think once you get to know a transperson, especially if you don’t know they are a transperson, you get to see that there really isn’t that much to be afraid of,” Waldrip said. “I wouldn’t say that there is anything to be afraid of unless you really don’t like reevaluating your life at all.”

Senior shares challenges of being transgender

Get stories like this in your inbox

Subscribe