Nearly 100 years ago, 10 brave men chartered the now historically black fraternity Kappa Alpha Psi on IU’s campus.

Originally named Kappa Alpha Nu, the fraternity was founded in January 1911. It is the only national fraternity — white, black or otherwise — founded at IU. It is also one of the first historically black fraternities to form on a predominantly white campus.

Members of the national chapter came to visit IU this February to begin planning Founders’ Day, the centennial celebration of its founding at IU next January. As many as 800 Kappa alumni are expected to attend.

“The founders of Kappa Alpha Psi paved the way for all students that came after them,” said Eric Love, director of the office of diversity education and one of the chapter’s advisers. “They didn’t initiate change just for Kappa Alpha Psi members. They initiated change on the IU campus and the community for all students of color.”

The fraternity brothers took a tour of places on the IU campus that are significant to their fraternity’s history. They call this the Kappa Trail and hope to mark each location’s historical importance.

“We are at home,” said Richard Snow, executive director of Kappa Alpha Psi, Inc. “This is where we were born.”

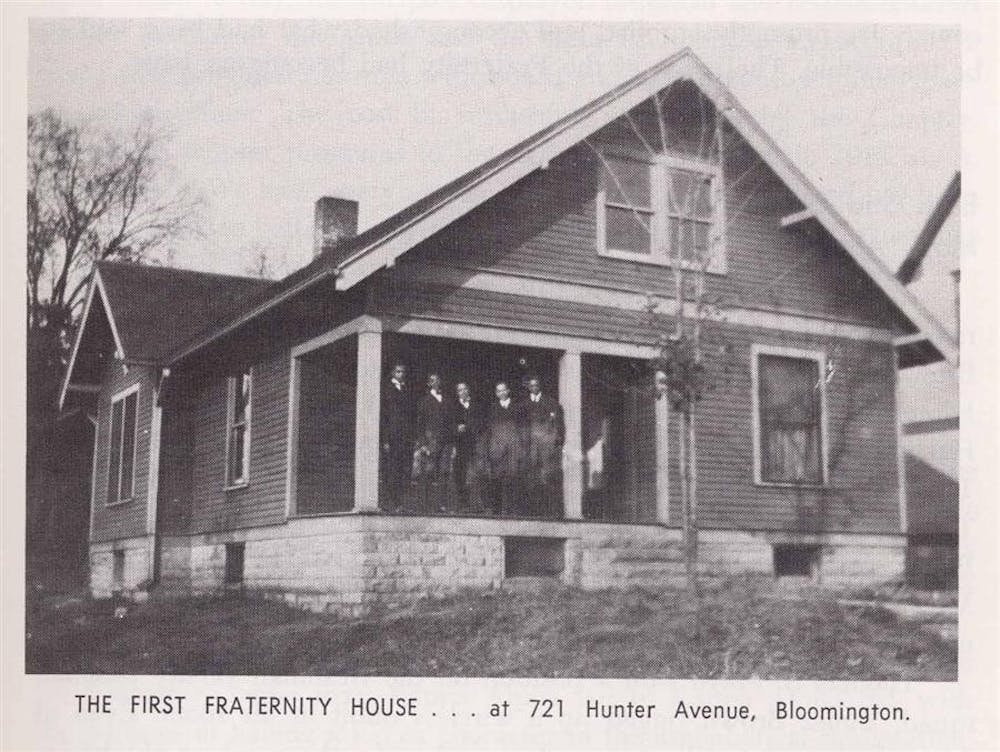

Their first stop was what used to be the Alpha chapter’s home on the IU campus.

Although the Kappa members have lived in various houses throughout the years, the IU Foundation and police station building on 17th Street and Jordan Avenue was the first house IU officially recognized. It was Herman B Wells’ wish that the Kappa house connect with fraternity row, not isolated from the rest of campus.

Members lived in the house from 1962 to 1995. In 1996, the Kappas moved out due to low membership, expensive repairs and lack of funds.

Several generations of Kappa Alpha Psi brothers stood in awe of their former home, many taking pictures.

One of the group’s other stops was the Jordan River, where Elder Watson Diggs and the other founders swam because they were not allowed in the public pools.

For many Kappa Alpha Psi members, experiencing IU for the first time was highly emotional.

Kevin Johnson, national convention meeting planner, had never visited IU before.

“To be able to be standing on hallowed ground where my founders were and to see where members lived for over 30 years is very emotional,” Johnson said. “I’ve seen pictures, but to be able to see it for yourself gives me a deeper appreciation for what the founders did.”

According to “The Story of Kappa Alpha Psi,” a chronicle of the fraternity’s history, by William L. Crump, in 1910 only a handful of black students were enrolled at IU. Their existence was almost completely ignored by white students, and they could go weeks without seeing each other on campus.

Blacks were denied use of entertainment and recreational facilities, could not participate in contact sports and were only allowed to show their athleticism in track and field.

After the fraternity was chartered, the struggle had just begun. During the early 1900s, the Kappas were denied a place to meet, and IU refused to recognize them as a chapter after they were chartered.

The main goal of the fraternity was to push black students to strive for perfection, although the administration expected virtually nothing from its black students.

A support system during the early years

The founding members of Kappa Alpha Psi could do little more than attend class.

And little progress was made when George Taliaferro, an All-American football player at IU and the first African-American drafted by the NFL, became a member of Kappa in 1948.

Taliaferro, now 83, met three of the men that founded Kappa Alpha Psi during his time as a student at IU, including Ezra Alexander and Byran K. Armstrong.

The members told Taliaferro about their experiences at IU, and he said “I was living the same thing.”

With no social activities to get involved in at IU, Taliaferro said he spent his time with fellow black students, which made it seem like a natural choice to join the fraternity.

During Taliaferro’s time at IU there were about 100 black students. The rivalries between the various fraternities were never too intense because black students only had each other to depend on.

“We were nice to each other because we didn’t have anyone else to be nice to,” Taliaferro said.

Kappa Alpha Psi provided a shield for the brothers.

“The older big brothers helped us adjust and they forewarned us ‘don’t go here, don’t go there, don’t stay out late and don’t be on campus alone,’” Taliaferro said. “Survival techniques were all in place.”

Black students were not allowed to eat in the restaurants, live in the dormitories, swim in the pool or go to the movies, Taliaferro said. There was one table in the commons where African-Americans were allowed to eat — but no more than eight people could sit there.

Taliaferro was in pursuit of knowledge and he did not allow racism to get in the way.

“That’s why I stayed here,” Taliaferro said. “And that’s why I took all the crap I had to take — because I was filling my head with information.”

He and his fellow Kappas pursued academic achievement and would frequently study together.

“Kappa Alpha Psi provided a social intellectual environment, community involvement and at the end to the beginning, overall achievement,” Taliaferro said. “It inspired you to be the very best that you can be, and you have a brotherhood in support of you.”

A shelter from the storm

The campus climate was different in 1965. Although the campus was not institutionally segregated, it was still not welcoming to black students.

Edwin Marshall, vice president for diversity, equity and multicultural affairs, said it was not rare for a black student to hear racial epithets out of a car window or have someone make a remark on their way to class.

“A lot of African-American males looked at it as a shelter from the storm,” Marshall said. “It provided that place that one could go both physically and mentally that could be supportive.”

Some fraternities were not as congenial with Kappa Alpha Psi, but no outward racism within the fraternity system took place, Marshall said.

Vincent Isom, director of the Thomas I. Atkins Living-Learning Center and Kappa Alpha Psi member since 1987, said sometimes living on fraternity row was an “on the outside looking in” experience.

The Kappas used to host events at the house such as “Christmas with the Kappas.” They had parties, educational programs and networking opportunities that “kept people to and from the house,” Isom said.

Isom said because it was the Alpha chapter’s house, it was the “home away from home” not only for those members, but for brothers of all chapters. The brothers formed study groups as a means to strive for one of Kappa Alpha Psi’s main principles, academic excellence, Isom said.

“You had your brothers to motivate you,” Isom said.

Changing times, reassessing purposes

Although the times have changed, current members of the Kappa Alpha Psi’s Alpha chapter joined for reasons not too different from Marshall and Isom.

As a resident of Kokomo, sophomore Aaron Barnes could relate to the history of the fraternity.

“The fact that it was founded on a majority campus almost 100 years ago spoke volumes to me,” Barnes said.

IU can still be an isolating place for black students. Sophomore Burnell Grimes Jr. said being a member of Kappa is beneficial because he knows his brothers will be willing to help him with his schoolwork.

“Sometimes you are the only African-American student in a class,” Grimes Jr. said. “And you may not feel comfortable going to a Caucasian counterpart for help, but you may feel comfortable going to an African-American who has been in the class or is taking it right now.”

Love said he has seen a vast improvement in the men of the Alpha chapter: their GPA average has gone up, their presence has increased on campus and their reputation has improved.

He said the Alpha chapter should be the epitome of Kappa Alpha Psi as the fraternity approaches its centennial.

Kappa Alpha Psi is a part of both the National Pan-Hellenic Council and has recently been reacquainted with the Interfraternity Council.

Taliaferro was invited to a Kappa luncheon at IU, and he was impressed with the brothers he met.

“I let them know that I can’t begin to tell you how proud I am of your conversations, what you are talking about, the way you appear and the way you carry yourselves,” Taliaferro said. “The young men that I see here today, I am proud to say I am your brother.”

A shelter from the storm

Get stories like this in your inbox

Subscribe