The man’s body hung from a piece of rope attached to a construction scaffold, lifeless in the chilly winter air. Around his neck was an expertly tied hangman’s noose. His highly polished combat shoes barely touched the platform. The dead man was clothed in blue jeans, a dark windbreaker, and gray woolen gloves. Dust and debris covered the ground just below his clean, black shoes.

It was 7 a.m. on Feb. 15, 1960, when the morning construction crew discovered the man hanging in the partially completed IU football stadium. An investigation began that morning and ended two months later. But for the father of the man in dark clothes and clean shoes, the case is far from closed.

At about 7:15 a.m., Bloomington Chief of Police and Monroe County Deputy Coroner George E. Huntington received word that a man’s body had been discovered in the new stadium. He arrived on the scene fewer than 10 minutes later to find the area crowded with police officers, university

officials, and local reporters.

After surveying the scene briefly – and without securing the area or collecting any evidence – Huntington pronounced the cause of death as suicide. He told the crowd that the man had jumped into the noose and broken his neck. Price Cox, an investigator for the IU Division of Safety, added that the man had died instantly.

Huntington then went back, removed a wallet from the man’s jeans, and identified him as Airman 3rd Class Michael F. Plume, a student at the United States Air Force Language School at IU. The workmen then lifted the body in the air and untied the rope at the top of the scaffold. The crew lowered him to the ground and cut the rope, leaving the noose attached to the body.

Michael’s body was loaded into a vehicle for transport to Day Funeral Home in Bloomington. Having completed his investigation at the stadium, Huntington left the scene and went to the funeral home, where he made arrangements with an employee to handle the body.

Huntington also placed a call to Dr. Neal Baxter, Monroe County coroner, to discuss the need to perform an autopsy. Since the cause of death had been determined at the scene, Huntington and Baxter decided that an autopsy was unnecessary. However, Baxter, still seeking a motive for the suicide, scheduled an inquest into the death for the following day.

By 7:45 a.m., the first stage of the investigation into Michael Plume’s death had been completed. The process had taken about half an hour.

That same morning, nearly 1,100 miles to the west in Evergreen, Colo., 42-year-old William Plume stayed home from work with a cold. His youngest son, 5-year-old David, kept him company while his wife, Marjorie, visited a neighbor. When the phone rang at about 9 a.m. Mountain time, David answered it and roused his father from his sickbed.

The caller was a reporter from the Denver Post. He wasted no time in explaining the purpose of his call: He wanted comments on the story that Plume’s oldest son, 18-year-old Michael, had been found dead in Bloomington, Ind. Stunned, Plume told the reporter he didn’t know anything about that. He had spoken to Michael just three days ago, and he had seemed fine.

He quickly ended the call and found the phone number Michael had given him in case of emergency. He dialed it and asked to speak to his son. After a few moments, he was connected to Capt. Edwin H. Shuman, commanding officer of Michael’s unit. He asked if Michael was there.

Shuman answered without preamble: “He hanged himself last night.”

Plume felt like he had been hit. Shuman’s words were the first indication he had received that Michael had taken his own life. With a growing feeling of disbelief, Plume called his neighbor’s house and told his wife to come home right away.

When his wife and their neighbor arrived, Plume broke the news to them. The neighbor left to pick up Michael’s five younger brothers from school. Plume had to break the news of Michael’s death yet again, this time to Gordon, 16; Stephen, 15; Russell, 12; Larry, 10 and David, 5.

Later that afternoon, Plume received a call from a family friend in Indianapolis who told him that an inquest was scheduled for the following day. He immediately decided to attend.

Plume arrived in Bloomington on Tuesday, Feb. 16 – the first of approximately two dozen visits he would make to the city in the course of investigating his son’s death. He could not believe that his son – a happy young man who had given no indication of any significant problems in his life – would suddenly kill himself.

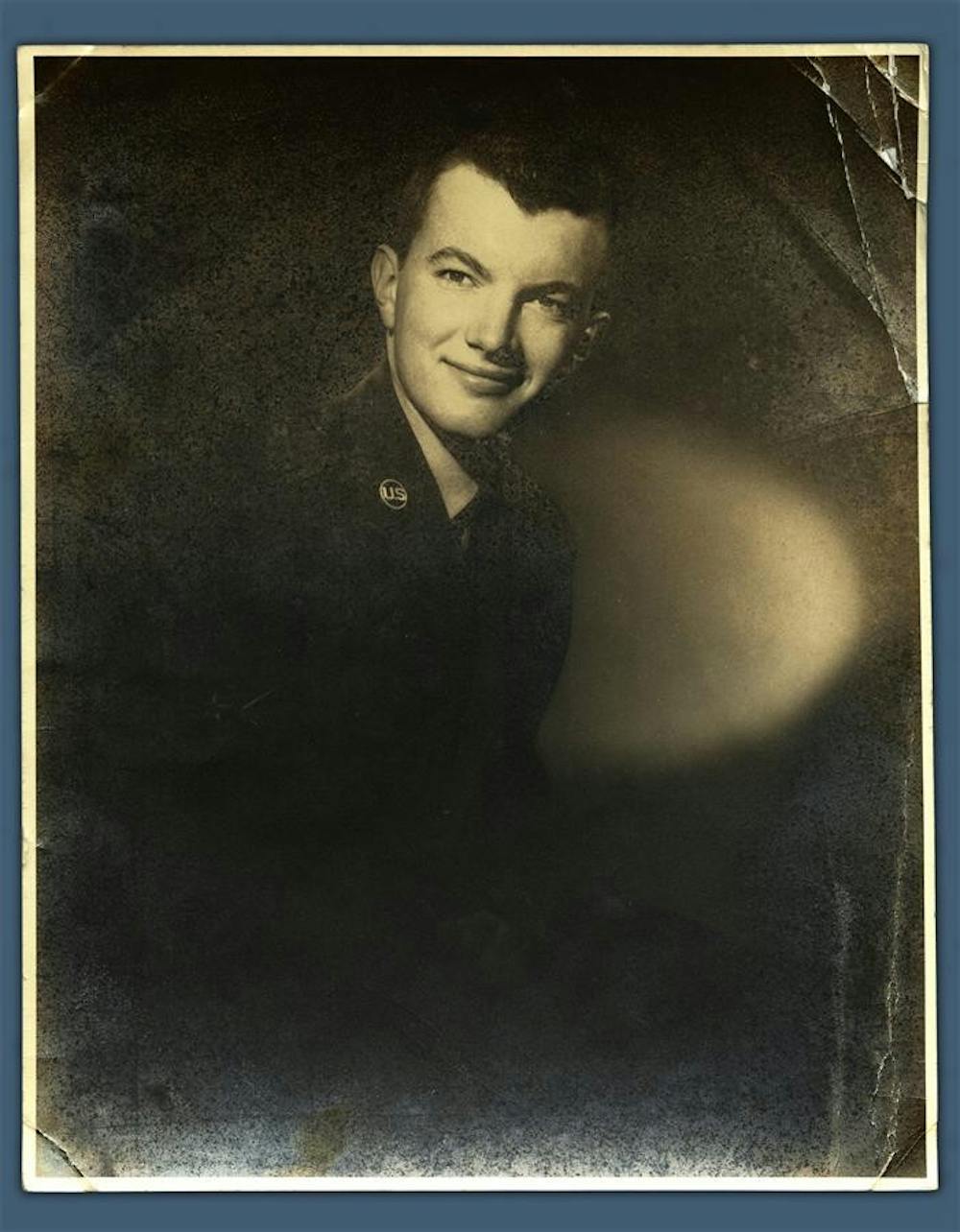

By all accounts, Airman 3rd Class Michael F. Plume was an outstanding student who enjoyed life at the United States Air Force Language School. He had enrolled in the Air Force in July 1959, shortly after high school graduation. He had planned to specialize in electronics until Air Force officials learned that he had studied Russian in high school and sent him to the their newly inaugurated language school at IU to study Slavic languages.

Michael arrived in Bloomington in October 1959, one months after his 18th birthday, and quickly established a reputation as one of the top students in the language school. He enjoyed being able to combine his Air Force training with higher education, telling his family: “I’m doing my military service and getting college credits at the same time.”

In letters to his family and friends, he described Indiana as a beautiful place, sometimes enclosing his photos of Bloomington and the IU campus. He became popular with his fellow airmen and made many friends on campus. In a letter to a friend sent three weeks before his death, he wrote: “Man, this is the life!”

Michael last spoke to his father Friday, Feb. 12. He talked about a Russian exam he had recently taken. It had been difficult, but he thought he had done well. The last thing his father told him was to take care of himself.

Michael laughed and said he would.

After the inquest, Monroe County Coroner Dr. Neal Baxter told Bloomington’s Daily Herald-Telephone that he would issue a ruling on Michael’s death within a week. The official verdict, however, did not come until April 15, 1960, nearly two months later: suicide, motive unknown.

Plume completely disagreed with the verdict. By that point he strongly believed that his son had not killed himself. He began to focus on the initial investigation conducted by Huntington and Baxter. Plume believed they had jumped to the conclusion of suicide and consequently failed to conduct a thorough inquiry into his son’s death.

With pressure from IU President Herman B Wells and Dean of Students Robert H. Shaffer, Baxter eventually allowed the Air Force’s Office of Special Investigations to open an inquiry into the case. In June 1960, the OSI exhumed Michael’s body from his grave in Colorado and conducted an autopsy. They performed laboratory tests on his clothing and the rope, and conducted more than 200 interviews with family, friends, classmates, and everyone involved in the initial investigation, including Huntington and Baxter.

Plume had achieved his goal of an independent investigation into his son’s death. But there was a hitch: The OSI was merely a fact-finding agency and was prevented from providing any sort of opinions about its findings – that was left to Baxter.

To make matters worse for Plume, the Air Force would not provide a copy of the OSI’s report to him without Baxter’s permission. Baxter denied Plume’s request to see the report.

It wasn’t until after 1966, with the passage of the Freedom of Information Act, that Plume was able to obtain a copy of the OSI’s report from the Air Force. The report’s findings convinced Plume beyond a shadow of a doubt that his son did not take his own life.

One of the key conclusions was that, contrary to Huntington’s and Baxter’s reports, Michael had not died of a broken neck, nor had he jumped into the hangman’s noose from atop the scaffold. According to the autopsy conducted by the OSI physician, Michael had slumped into the noose, and the pressure of the rope had cut off his airway, resulting in death by strangulation. His neck had not been broken at all.

Then there was the matter of Michael’s shoes. Though the ground at the stadium had been covered with dirt and cement dust, the workmen interviewed by the OSI had reported that his shoes were highly polished and almost completely free of scuffmarks – even the soles. If he had walked into the stadium by himself, the workers questioned, how had he managed to keep his shoes so clean?

Michael had also been wearing woolen gloves. Though the Air Force-issued gloves had been dry-cleaned immediately following his death, the OSI sent them and the rope to the FBI for analysis. The FBI reported that there were fibers from Air Force-issued gloves on the rope, but there were no rope fibers found on the gloves that Michael had worn.

Furthermore, because Plume had requested the report through the Freedom of Information Act, he also received the Air Force’s internal memos, which Baxter had not seen. One read: “There is a reasonable possibility that the death might not have been suicidal, and if the death appears to be from foul play, we have a reasonable suspect.”

OSI agents learned through their interviews that three airmen, including Michael’s roommate, had been engaging in homosexual activity around the time of his death.

According to statements from the three airmen, one encounter had even taken place in Michael’s room while he slept.

Air Force regulations at the time made homosexual behavior grounds for dishonorable discharge – in fact, simply letting homosexual behavior go unreported could result in dishonorable discharge. Plume believes that Michael became aware of his classmates’ activities and, wanting to avoid a discharge, planned to report them to his superior officers – but before he could do so, his fellow airmen silenced him and made his death look like suicide.

In the years after receiving the OSI report, Plume met with a succession of Monroe County coroners in his attempts to have the suicide verdict changed. Baxter was the first to review the report, but the OSI’s findings did not sway him. He refused to change the verdict of suicide, although he did change the cause of death from “broken neck” to “strangulation.”

The verdict stood for more than four decades as three of Baxter’s successors – including George E. Huntington, who had played such a crucial role in the initial investigation – declined to change it. Finally, in June 2003, Plume met with current Coroner David Toumey in Bloomington. Encouraged by Toumey’s willingness to review the case, Plume prepared materials explaining exactly how the physical evidence supported a verdict of homicide.

More than a year later, in 2004, Toumey issued a finding of “undetermined.” For Plume, unwavering in his belief that his son was murdered, this was not enough.

At the age of 89, William Plume has been working on his son’s case for 46 years. He has always been clear about his objective in trying to reopen the case. Despite his firm belief that his son was murdered, he has no interest in pursuing a criminal case.

“I don’t give a hoot about who did it, or why it was done,” he says. “I think I know both pretty close, but I don’t care about that.”

Plume’s only goal is to have the Monroe County coroner change the official ruling on Michael’s death to homicide. After years of trying to work quietly with the coroner’s office, this year he has changed tactics and made his efforts public. In September 2006, he put together materials summarizing the case and mailed them to more than 80 influential people in Bloomington and Monroe County, including the mayor, city council, county prosecutor, county commissioners, chamber of commerce, IU administrators and faculty, IU trustees, and local media.

Plume’s hope is that enough people with political clout will apply pressure to Toumey and persuade him to change the verdict from “undetermined” to “homicide.”

Plume’s relentless pursuit to change the verdict is deeply rooted in his commitment to his family. He believes that Michael’s five younger brothers – now grown men with children of their own – deserve to have the records show that their brother was murdered. As he told Michael’s mother when he began his efforts more than four decades ago: “Someday they’ll be grown up, and they will want to know what happened to their brother. I’m going to find out.”

Who killed Michael Plume?

In 1960, a father lost his son. He’s spent the past 46 years searching for answers.

Get stories like this in your inbox

Subscribe