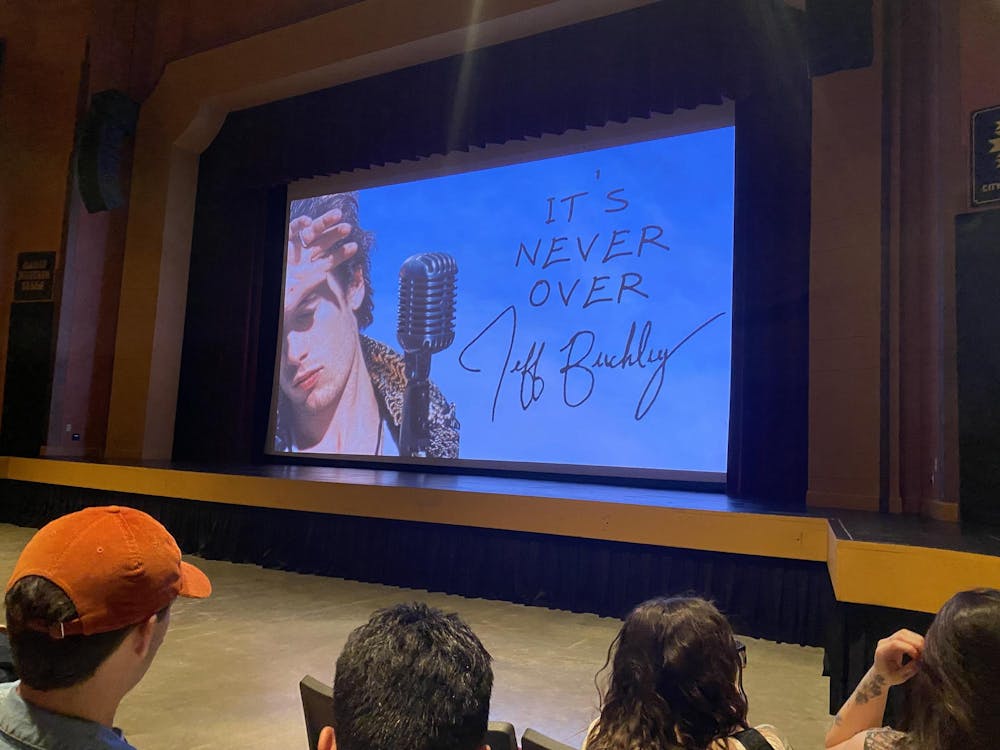

A crowd full of people wearing Doc Martens with tattooed legs gathered in the Buskirk-Chumley Theater. “Come into my world,” Jeff Buckley whispered as he leaned into the camera, and they did. On this warm late-August Thursday, Bloomington would again be inspired by a timeless musician.

In “It's Never Over, Jeff Buckley,” a documentary about the life and death of the late-’90s singer-songwriter, film director Amy J. Berg exemplifies the icon in a story about aspiration and our relationship, both perceived and real, to our heroes.

“It made me never, ever want to stop singing,” Bloomington resident Zara Shipley said after the film. Shipley co-founded a band inspired by Buckley called “We’re Welcome.”

The film is stylized and brash with flashing edits and animations over grainy ‘90s archival footage. Although lively and entertaining, it is honest and extremely sentimental. Berg takes Buckley’s story seriously, spending most of its time interviewing the women he loved most including his mother, Mary Guibert, as well as musician Joan Wasser and actress Rebecca Moore, whom Buckley had relationships with.

Buckley displayed vocal talent early, covering famous songs to almost exact replication. As the documentary explains, Buckley had a special bond with his mother who raised him herself after his father left home to pursue a career as a musician.

Unfortunately, his father overdosed and died at 28 after an on-and-off relationship with his son. For the rest of the documentary, his father’s tragic death looms over the story and threatens to be the parallel to Buckley’s fate.

Around halfway through the film, like the effect his singing had on people, I felt my guard go down, and Buckley’s vulnerability to be relatable. I began forgetting I was supposed to be writing this column as the film, supplemented by Buckley’s music, made me consider my own story. Despite being 27, born just a few months after Buckley’s accidental drowning in 1997, I couldn’t help but compare Buckley’s situation to my own life, also sculpted under the weight of “don’t become your absent father.” I wasn’t alone in having an emotional reaction to the film, as other Bloomington residents sniffled and some men coughed and shifted in their seats as they balanced the weight of the story.

At its core, the documentary is about the effects of aspiration on identity. Buckley’s persistence in inhabiting both positive and negative sentiments in his life is on clear display, showing intense empathy as both blessing and a curse. In doing so, the film doesn’t over-sentimentalize Buckley’s life. In one scene, Buckley gets on stage in his estranged father’s coat and performs a song his father wrote about leaving him. It was a powerful moment.

Toward the end, Buckley is asked about a common thread in his different inspirations and references, to which he replies, "mindless hero worship.” It causes you to consider the current internet trend of "the performative male," a cliche that often includes listening to Buckley. The film makes no effort to hide this tussle between being earnest and performative as Buckley himself deals with the same issues.

IU junior AJ Wilson attended the documentary showing. Wilson, who aspires to be a vocal performer, started listening to Buckley after going through an emotional time in high school.

“My grandmother was diagnosed with brain cancer,” Wilson said. “His wide range of emotions in his discography was something that I could pick a few songs and decompress and process everything I was thinking about.”

Buckley’s emotions are raw and infectious, and their ability to transcend is clear, as he stands atop the bottom left corner of the screen and strums his cover of “Hallelujah” as the crowd holds its breath. Buckley, only a little larger than life, faces the camera like he's performing to the crowd in the theater, and for the moment it’s as if he’s really standing in front of us. There is something so obviously palpable while he sings. This is as close as anyone will ever get to the experience of hearing him play live again. At least in that theater that night, performative or not, Buckley captivated us.

I first listened to the song “Dream Brother” after reading a story about Buckley writing the song for his friend who was becoming a father, warning him to not become like Tim Buckley. It stuck with me because I thought of my dad, my brother, and our relationships, or lack thereof. Sitting between half 20-somethings and half gray-haired people, I felt guilty for being there. I too knew the protective feeling of something I felt was secretly mine. Was I flawed in my attraction to Buckley? Was my gravitation towards tragedy an innate component of me that I had long ago rationalized? Was my comparison of my life to Buckley’s — despite not being a die-hard fan — a contradiction to the values his career represented?

Berg doesn’t seek to force-feed us answers, but instead exemplifies through the lens of Buckley’s life that it’s the questioning that makes up our identity. The film shows through Buckley’s life that perhaps we are more than other people's perception left behind for us.

In the most poignant scene Buckley is asked what he thinks he inherited from his late father. Without a pause, Buckley, looking into the eyes of the audience, confidently states, “People who remember my father.”