The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention considers someone being up to date on their COVID-19 vaccines as those who have received their primary vaccination series and the most recent booster dose recommended for their age group. For most Americans, the most recent booster dose is the bivalent booster vaccine authorized by the Food and Drug Administration Aug. 31.

Simply put, with this new dose, those 18 and older are considered up to date after they’ve received both their primary vaccination series and their updated bivalent booster — the same is recommended for children aged 5 to 17, according to the CDC. The original booster doses are no longer necessary for those who haven’t yet received them, though the CDC recommends those who have still receive the bivalent vaccine.

What is the bivalent COVID-19 vaccine?

The FDA recommended the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna bivalent COVID-19 vaccine as a single-dose booster shot to be administered at least two months following the primary vaccination series or previous booster vaccination. On Oct. 12, the FDA extended this authorization to children ages 5 to 11.

According to the FDA, the bivalent vaccines include components of both the original COVID-19 strain and the omicron variant to provide the highest possible protection against the virus. Hence, the suffix “bi” in “bivalent” refers to the fact it includes protection against these two different strains.

“It’s just more specific to those strains and theoretically should work a bit better on something that looks like those,” Aaron Carroll, IU’s chief health officer, said.

How many Americans have received the bivalent vaccine?

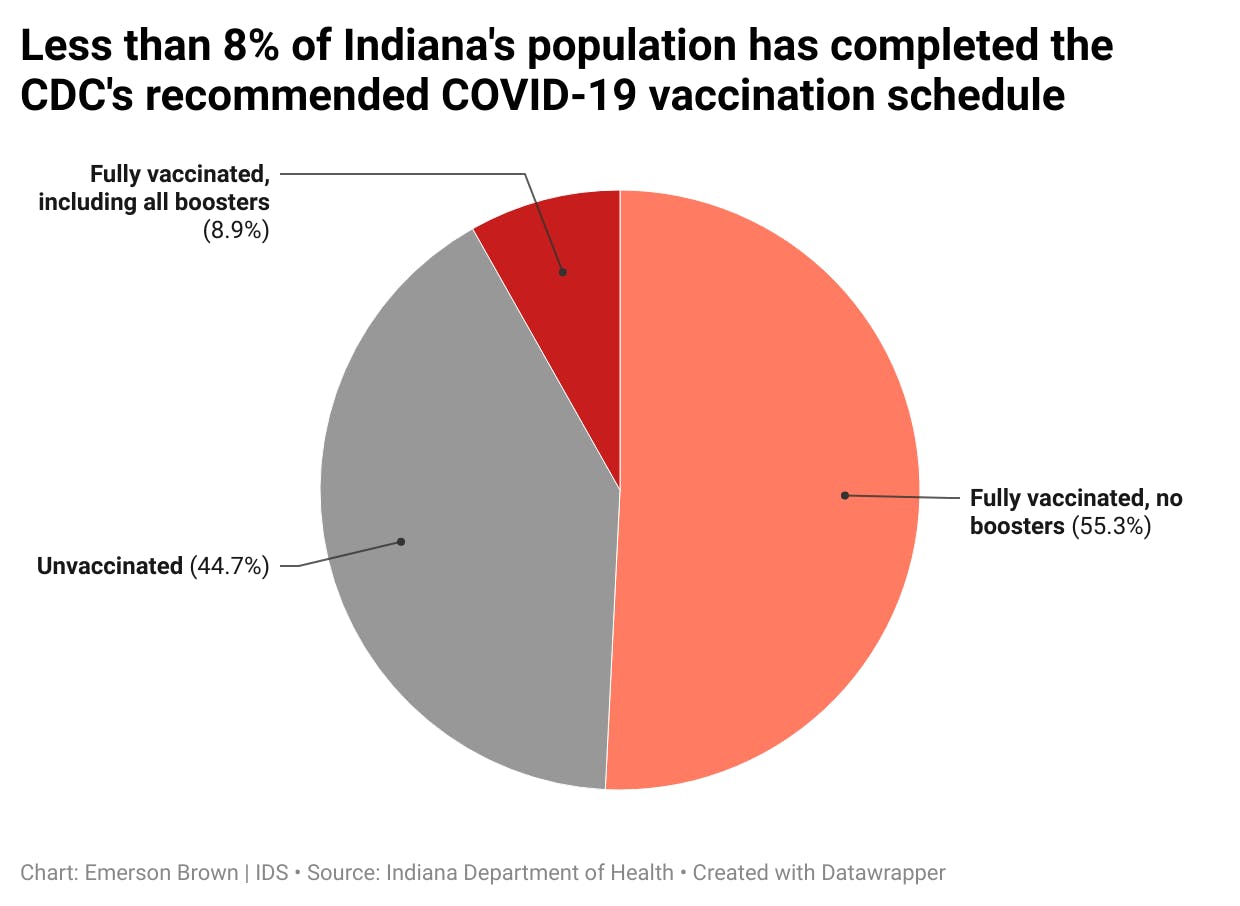

Data from the CDC shows that only about 10.1% of eligible Americans have received an updated booster shot, compared to 68.6% who have completed their primary series. According to the Indiana State Department of Health, 8.9% of Indiana residents are up to date on their vaccine series, which includes the bivalent vaccine.

However, as many as one in five Americans have not heard of the updated bivalent boosters, according to a survey published Sept. 30 from the Kaiser Family Foundation. Carroll said this is in part due to “COVID fatigue” — the idea that many Americans are simply tired of the pandemic and news surrounding it.

“It doesn’t feel like the same kind of crisis to most people in lots of places in the country, including Indiana,” Carroll said.

Carroll said those who are at lower-risk for major complications from COVID-19 are less likely to be persuaded by the current individualistic public health messaging. Instead, he argues for an approach to messaging centered on the protection of the community rather than the individual.

“That kind of broad messaging might resonate and work better and would feel more natural,” he said. “Nobody gets the polio vaccine because they think they’re going to get polio. We all get the polio vaccine because we know if everybody does it, we don’t have polio, and that’s the kind of broad communal messaging I think might work better.”

Graham McKeen, IU’s director of public and environmental health, agreed the hesitancy to vaccinate could be attributed to pandemic fatigue, but he also placed some blame on what he said was confusing communication from organizations like the CDC.

“There are times where I’ve had to sit down with some newly released guidance and go through it and map it out,” he said. “If I’m having to do that, and I’m having that much trouble understanding what they’re trying to communicate to everybody else, then I can’t imagine what the general public is thinking.”

Will there be more booster shots in the future?

Top infectious disease experts, such as Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, have suggested the COVID-19 vaccine could become an annual vaccine similar to that of the annual flu shot.

“That’s a really possible, if not likely, outcome,” Carroll said. “If it turns out this becomes seasonal, like we have winter spikes like we do with the flu, then come August, September of each year, they roll out a new shot.”

McKeen went a step further and suggested we could theoretically see a new COVID-19 shot as often as every six months because of the ever-changing nature of the virus, but he said many Americans just wouldn’t want to get a shot that often.

“It is so genetically divergent from where it was a year ago, and so it seems to mutate faster than some of these influenza viruses that we see,” he said. “That doesn’t bode well for us, and I don’t think people want to get shots every three to six months”

What about the new omicron subvariants?

In a weekly report published Oct. 21, the CDC detailed the two new omicron subvariants, BQ.1 and BQ.1.1, which it describes as “grandchildren” of the dominant BA.5 strain. Data shows the two subvariants “seem to be spreading relatively quickly so far,” but the CDC notes they make up only a small proportion of cases.

Carroll said he anticipates an increase in COVID-19 cases as it gets closer to winter, but it’s difficult to tell now whether such an increase would look like the omicron wave earlier this year or relatively minor in comparison.

“In a bad flu season, maybe we see a hundred-ish deaths a day — we’re still seeing way more than that with COVID,” he said. “Even if it increases, that’s concerning. The question is, will it achieve omicron or previous wave levels, or will it just look like a bad flu season. We just don’t know.”

Where can I get the updated booster in Bloomington?

In Bloomington, one can receive the bivalent vaccine at various CVS and Kroger Pharmacy locations, Walmart and Sam’s Club as well as at the Monroe County Public Health Clinic, IU Health Bloomington Outpatient Pharmacy and Genoa Healthcare, according to the CDC.

Students, staff and faculty can also make an appointment with the IU Student Health Center to receive the Pfizer primary-series or booster vaccine.

Correction: A previous version of this article misstated which locations offer the bivalent vaccine.