This is the fifth column in a weeklong series celebrating Banned Books Week, which celebrates the freedom to read. Each column will review a different frequently challenged book.

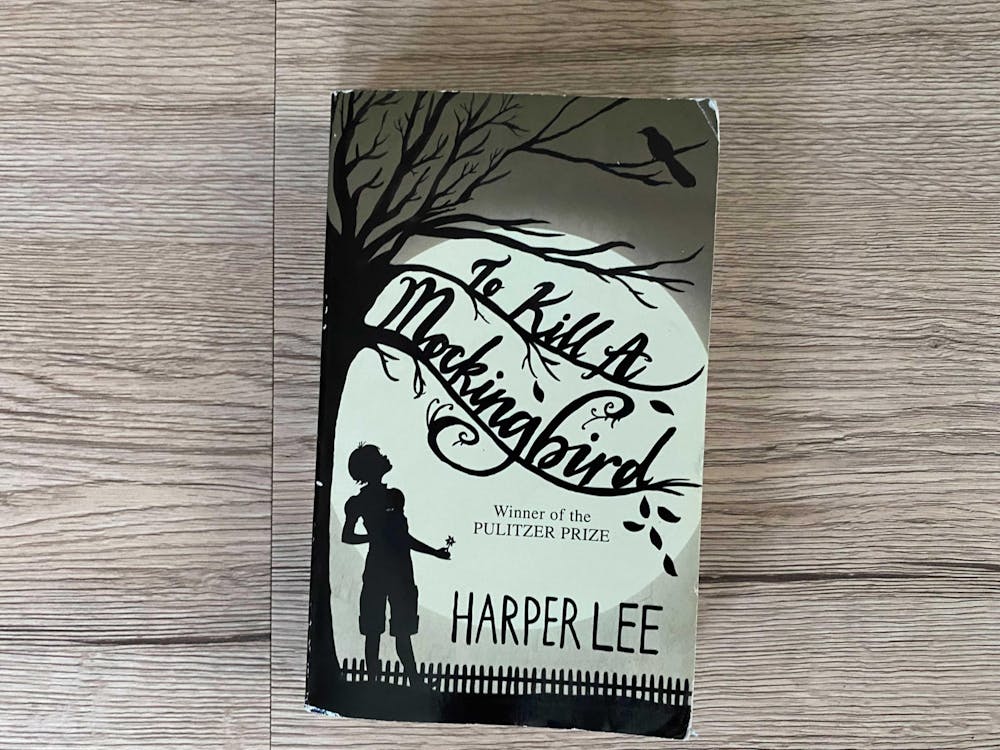

“To Kill a Mockingbird” by Harper Lee

“You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view … until you climb in his skin and walk around in it,” Atticus Finch tells his daughter Scout in “To Kill a Mockingbird.”

These lines, lifted from Harper Lee’s famous work, adeptly sum up a core reason why the book should stay in schools’ curricula and off of banned book lists. This novel broaches hard questions and integral character development to tell a story about the fictional town of Maycomb, Alabama.

It features the conflict when the protagonist’s father, the moral town lawyer, is tasked with defending Tom Robinson, a Black man falsely accused of sexually assaulting a white woman.

It also arguably highlights the perpetuation of a white savior complex and uses the N-word, both traits I don’t condone myself but cause it to land it in school districts’ banned books stacks. Teaching literature in schools is important, as is teaching critical thinking skills, and in my experience, the two have often been linked.

Reading “To Kill a Mockingbird” did not make me think it was OK for me to use the N-word, but it did spark necessary conversation about the way racism is ingrained in historical and contemporary society when my own school taught it.

It, like many other books on banned lists, taught me lessons about empathy and character I would be lesser without.

Lee takes a scalpel to the human condition, exposing both the kindness and cruelty of her characters. Few are static, and Lee allows readers to watch as characters’ understandings shift.

The Finches’ neighbor, Boo Radley, is one of my favorite fictional characters. As readers, we don’t see his character development, but others’ perceptions of him chart where they are in their respective growth. Originally, Scout and her brother Jem see Radley as a sort of manifestation of superstition. They make up stories about him, a recluse, but he ends up saving the children at the end of the story.

“He was real nice,” Scout says to her father after Radley rescues the children from an attempted stabbing incident. “Most people are, Scout, when you finally see them,” Atticus responds.

This dialogue exchange, constituting a total of 13 words, argues the book’s importance itself.

Published in 1960, Lee wrote a candid story addressing the racism which would have been endemic to her time. She does it through the narration of Scout, a child, and in such a way the story is accessible to fellow children. I read it for the first time in middle school, but it’s a book worth going back to regardless of your age.

“As I made my way home, I thought Jem and I would get grown but there wasn’t much else for us to learn, except possibly algebra,” Scout says at the end of the book.

Thankfully, I’m finished learning algebra, but books like Lee’s ensure I won’t ever finish learning about the complexities of characters.