This is the fourth column in a weeklong series celebrating Banned Books Week, which celebrates the freedom to read. Each column will review a different frequently challenged book.

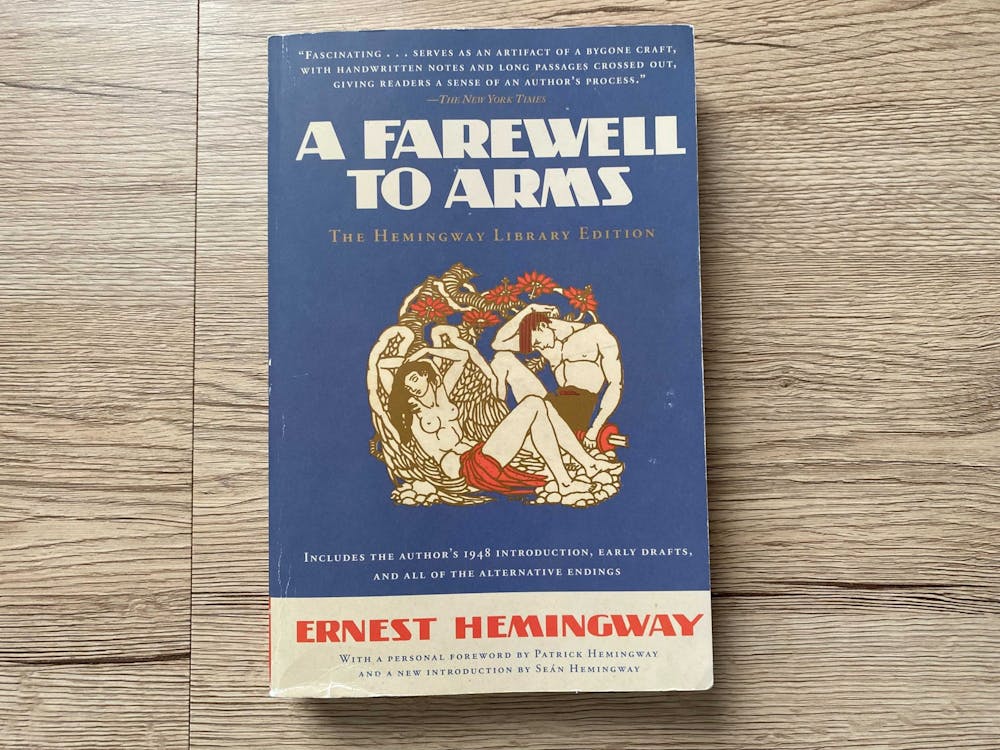

“A Farewell to Arms” by Ernest Hemingway

Warning: If you don’t have that friend who is annoyingly pretentious about books (common qualities include possessing a designated novel for public transit rides, an emotional support short stories collection, an Excel sheet to log annual reads), you might be that friend. Shocking no one, I am that friend.

In my unironic Excel sheet detailing my latest books — readers, please know I am also shaking my head at myself and publicly exposing this side of my personality as penance for having it — I rate each book I read on a scale of 1-10. Truthfully, books seldom receive lower than a six because writing a book is an impressive feat, one I can’t stand belittling even in my lowly book log which has a target audience of one (me). Ernest Hemingway’s “A Farewell to Arms” scores a solid 7.8/10.

“A Farewell to Arms,” often receiving the elusive “classic” title from English instructors and from boys with a concerning number of red flags, tells the story of Frederic Henry. Henry is an American lieutenant in the ambulance corps of the Italian Army during World War I.

He falls in love with a nurse’s aide named Catherine and their story makes up most of the novel. It offers a commentary on commitment to people and endeavors, the realities and fantasies of war and the role of love in all of the above.

Hemingway is often critiqued for the flat, one-dimensionality he imbues his female characters with. Catherine is a character I’ve always wanted to sympathize with but never quite could.

She and Henry begin a sort of scripted love, which Hemingway would have us believe later turns genuine. When we first meet Catherine, she’s grieving the death of her fiancé. In her grief, she allows herself to accept Henry’s originally hollow promises, settling for the illusion of love in place of the actual thing.

This self-deception does present an interesting track of questions the reader can examine for herself: Is it better to be passionately wrong or lukewarm toward your surroundings? Better to recognize harsh truths or to be so disconnected from reality that you accept blatant lies? Hemingway might inadvertently provoke the questions, but most of the work is on the reader.

I’m usually not partial to one kind of syntax or another. I recognize the greatness in Mark Twain’s short lines as much as Fyodor Dostoevsky’s winding ones. But I generally find a Hemingway sentence — though pioneering a new kind of literary style and influencing writers from Jack Kerouac to Joan Didion — just so painfully boring.

However, anyone who can sneak the line “It was all balls” into a work widely classified as great literature gets at least a modicum of respect from me.

There are several aspects to analyzing Hemingway that make me laugh. Being challenged in 1929 for its “painfully accurate account of the Italian retreat from Caporetto, Italy” and its 1980s classification at a New York school for being a “sex novel” are chief among them.

Censorship is no laughing matter, but isn’t it just a little funny that the reason it was banned was for its acknowledged accuracy? And truth be told, as a cradle Catholic enduring more than a decade of private school regulations, I’m hysterical at the idea of anyone thinking of this book as a “sex novel.” Catherine does end up pregnant — but she dies shortly after childbirth, so I’d argue that this one could actually be used as an abstinence-only sex-ed prop.

The final point I find amusing has less to do with Hemingway and more to do with the public’s adoption of his words. Who among us hasn’t seen the following lines lifted from the book and pasted onto an inspirational Pinterest board?: “The world breaks every one and afterward many are strong at the broken places.”

I won’t argue the beauty of this line, but I would encourage the people who use it to remember context often matters. For example, in this case, Hemingway immediately follows that encouragement with: “But those that will not break it kills.”