Jazz is Black. Hip-hop is Black. R&B is Black. Yet some of the biggest names in those genres are not. Think of Bill Evans for jazz, Eminem for hip-hop or Adele for R&B. Of non-Black names like these, few are respected, but why?

In any space made by Black people, there's going to be some non-Black people who want in. With the societal space Black culture holds right now — being both persecuted and celebrated — it creates a difficult situation: how can non-Black people participate?

I've written about how it can go wrong before. Sometimes non-Black people use Blackness as a stepping stone to other ventures, sometimes they ridicule Blackness to make a joke or sometimes they try to claim a space that isn't theirs.

It's much harder to deduce what makes some non-Black people in these spaces garner respect.

One of the earliest examples of this would be in jazz. The genre was popularized in the days of Jim Crow, which meant it led to deep conflict. Black musicians weren't on grand stages just yet, and white musicians never played with them.

Performance venues were still heavily segregated and that barrier wouldn't be broken until Benny Goodman came along. Goodman, a white man, decided to have a band of both Black and white musicians, caring only for the music they could deliver together.

Because of this, he was able to deliver one of the most important performances in music history. His jazz band played in Carnegie Hall — one of the most historic stages in American history — with half a dozen Black people.

The message was clear. Goodman only cared about making great music. He was aware of the racial realities surrounding jazz and his place in it but let the artistry speak for itself. This mentality led to other white jazz musicians making great contributions to the genre.

For a modern example, look at Kenny Beats, a white man who found himself producing songs for names like Denzel Curry, Rico Nasty and Gucci Mane. Kenny likes to be in the background in production and collaboration with Black artists, as opposed to other non-Black artists who center their work around themselves.

He even has a YouTube series where he showcases how he works with artists to make songs.

He doesn't take himself too seriously and has a fun rapport with his collaborators. This doesn’t mean he views the music he makes as unimportant — he just takes a backseat to the Black artists he's showcasing.

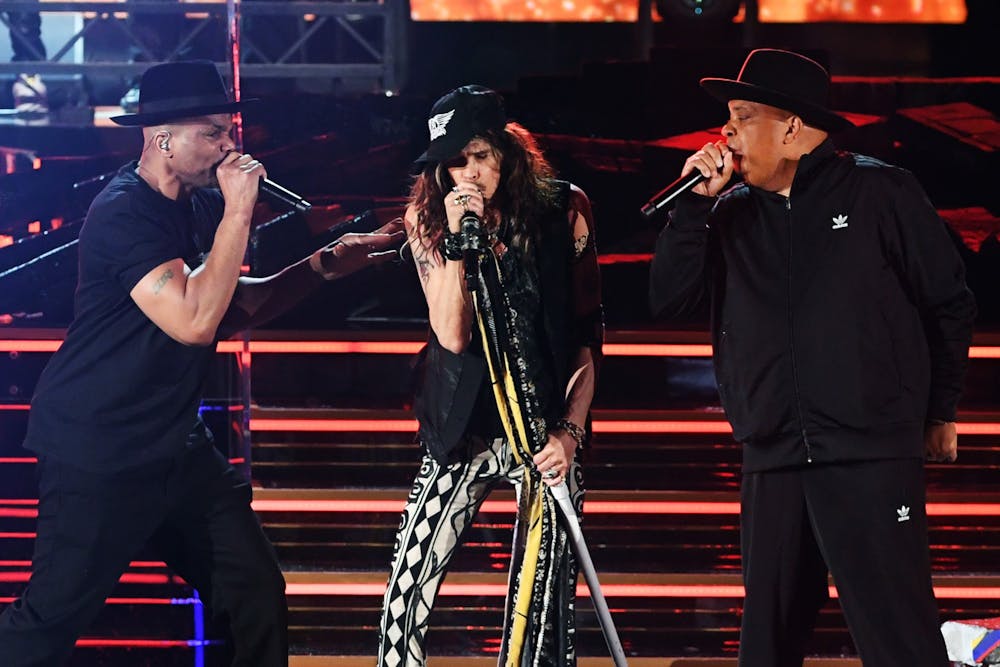

Maybe the most well-known example of white artists in Black music is the collaboration between rock band Aerosmith and rap group Run-D.M.C. The groups collaborated to make "Walk This Way," a song that mixed glam rock — a decidedly white version of rock and roll — and hip-hop.

The two groups were popular in their own genres, but their audiences rarely overlapped. This collaboration, along with a groundbreaking 1986 music video, brought change to popular music as a whole.

These examples give some understanding as to why some non-Black artists are respected in these Black music spaces. There are plenty more examples, like the Beastie Boys or the late Mac Miller, but the pattern remains: let the music be your motivation.

These artists recognize they're guests in a Black space, and while they focus on the art, they also take care not to disrespect the origin of the music.

That makes entering a Black space sound easy. Frankly, it is. It's just surprising how many miss the mark.