It was the year Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy were assassinated. It was the year the Mai Lai Massacre turned millions against the Vietnam War. It was the year segregationist George Wallace made a strong showing as Presidential candidate. It was the year that counterculture took its rancor to entirely new levels.

Turmoil defined the United States in 1968, but it was also a significant year in film.

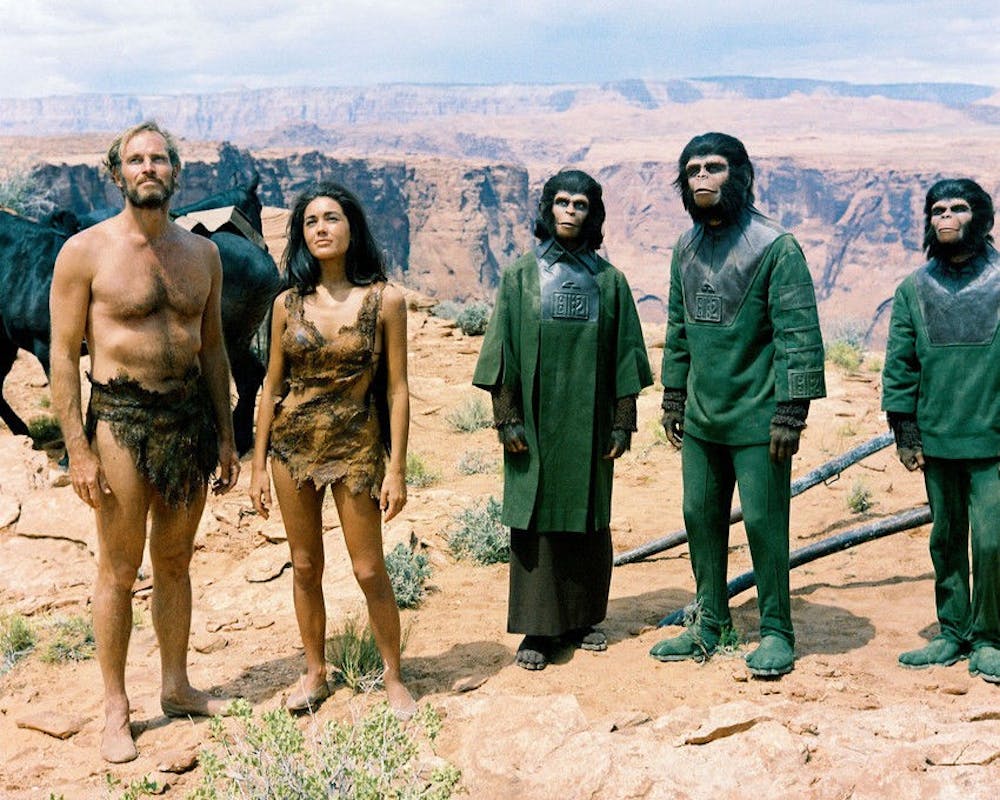

For example, “Planet of the Apes" is a movie in which astronauts find themselves captive in a future dominated by intelligent apes. These men find themselves facing the consequences of humanity’s pension for war and destruction, and must contend with the racism and bigotry of the Apes. This film was made in a time marked by racial conflict and Cold War tension, and few films are so evocative and pessimistic in how they approach such issues.

Transcending contemporary events, however, Stanley Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey” is one of the films released in 1968 and remains a lasting cinematic icon of the era.

"2001: A Space Odyssey" is a film about evolution and man’s relationship to the universe. In four brilliant acts, it follows the efforts of extra-terrestrial life to nudge mankind forward.

The first act follows a tribe of hominids struggling to keep a rival tribe off their land, when a monolith, apparently placed by an ultra-advanced alien race, appears, inspiring them to use the bones of a dead animal to beat off the tribe.

The second act takes place in a future in which man has colonized the moon on which they find another such monolith intentionally buried there long before man roamed the Earth.

Astronauts are sent on a secret mission to Jupiter to seek out extraterrestrial life, and are aided by a sentient supercomputer named HAL, which manages their spacecraft.

Triggered likely by embarrassment at the prospect that he made an error, HAL attempts to take over the mission from the human astronauts, resulting in an ultimate showdown between humans and the tools they created.

It ends – spoiler alert – with the last surviving astronaut striving towards his evolutionary fairy godmothers on a red-carpet array of colorful cosmological phenomena. He finds himself aging to his death before becoming reborn as a uteral fetus hovering above earth – a new hope for mankind despite the tumult caused by man’s own devices.

This was unlike any science-fiction film ever made. With ground-breaking special effects and scientifically accurate depictions of space travel, the film looks ahead of its time for even today. But as its Homer-referencing title suggests, it takes science fiction to a deeper, ever more allegorical level.

The film was intended to be an audio-visual experience, and has very little dialogue. It is cerebral, striving to evoke the subconscious by having the music neither guide nor reflect the action. The score makes use of classical music to evoke certain emotions in each act.

Richard Strauss’ elative “Thus Spoke Zarathustra” is used in moments of triumph, when humans have reached another victory in their evolution, such as when the Apes discover the bone or when the fetus hovers above earth, Johann Strauss II’s playful “The Blue Danube” is deployed in moments of awe, and eerie and dissonant "Requiem" by Gorgy Ligeti is used to evoke the supernatural and the extra-terrestrial.

Stanley Kubrick, who directed, produced and co-wrote the film with science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke, dared to defy narrative conventions and produce an ambiguous work conveying awe, hope, and terror. Who are the aliens? Why did HAL go bad? What does the ending mean?

Not everyone appreciated this aspect of the film in 1968, as people were used to science fictions flicks that honed in on conventions of cheesy dialogue and rampant violence. Over 250 audience members are said to have walked out of its New York premiere, including actor Rock Hudson, who asked, “Will someone tell me what the hell this is about?"

Clarke once said that "If you understand '2001' completely, we failed. We wanted to raise far more questions than we answered."

Indeed, many critics took it as a dystopian satire about man and the pitfalls of technology. However, audience members overwhelmingly saw it as a message of hope, rebirth and renewal.

But perhaps the most remarkable achievement of “2001: A Space Odyssey” is that while it was made in 1968, it contains a spark of genius applicable to many '1968s' yet to come.