It is often regarded as a mythical problem the United States has the luxury of avoiding, but it circulates in more than 29 countries. Adjectives used to describe it are barbaric, criminal and cruel. But, in truth, it’s a battle between cultural norms and health, deciding what to cut and what to save.

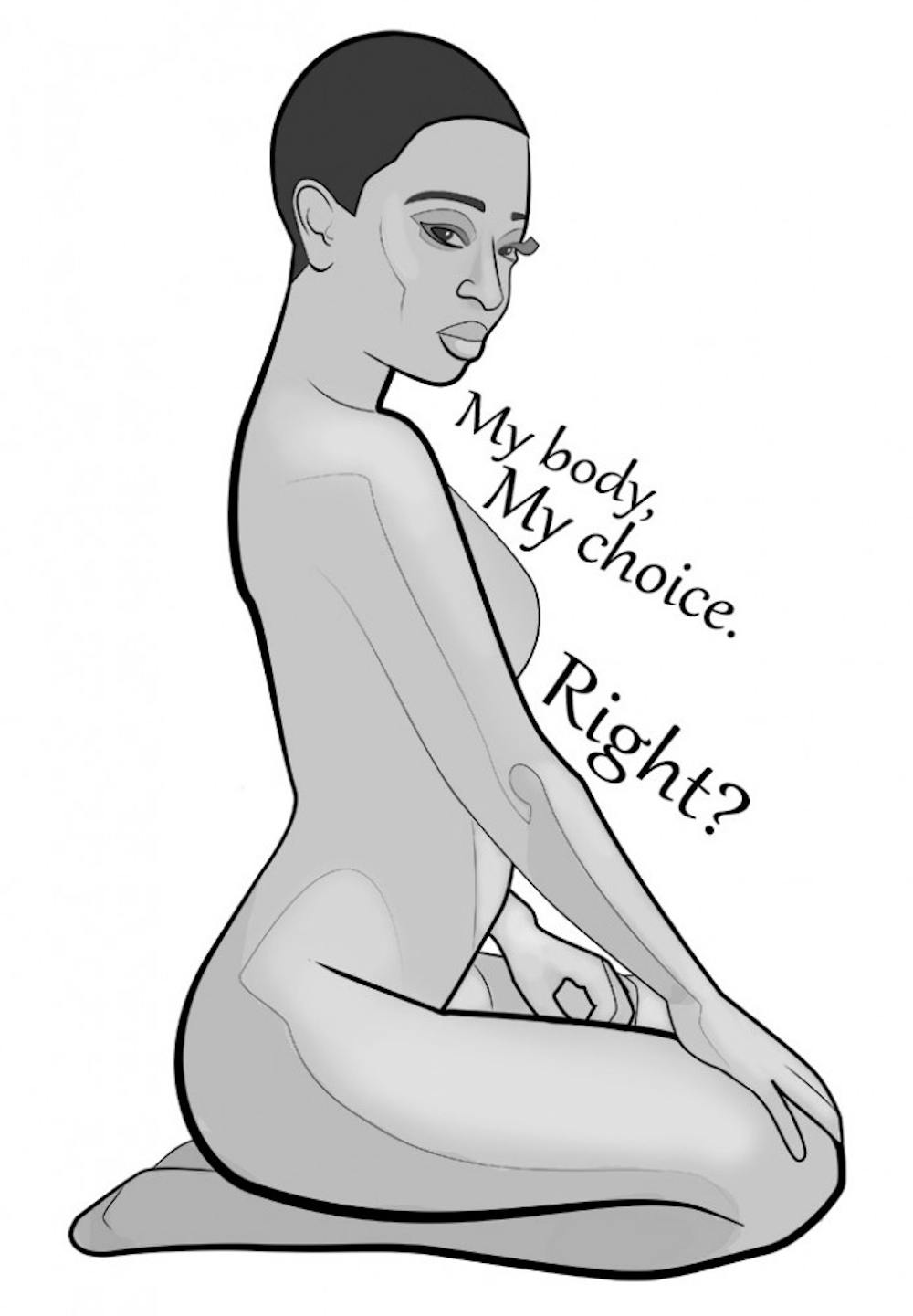

As defined by the United Nations Population Fund, genital cutting, or female genital mutilation, pertains to the removal, altering or injuring of female genitalia for non-medical reasons.

According to data published Friday by the Population Reference Bureau, the number of women who have undergone FGMs is estimated between 100 million to 140 million worldwide.

The data was released to coincide with UNFPA’s efforts to end FGMs and the establishment of Feb. 4 as the International Day of Zero Tolerance for ?Female Genital Mutilation.

The custom of genital cutting is a right of passage in some African and Middle Eastern cultures, standing as a symbol of purity and aiding in a girl’s chastity. Genital cutting, while often and wrongly associated with religious beliefs, is practiced as a form of ?communal unity.

But this otherworldly custom has more to do with Americans than we think. Though FGMs have been illegal in the U.S. since 1996, the PRB estimates about half a million women living in the U.S. have undergone or are likely to receive FGMs. This number has more than doubled since its last estimate in 2000.

The spike of FGMs in the U.S. is widely attributed to an increase of international immigration rather than a surge of actual procedures in the U.S. Yet our physicians on the forefront might not be prepared for a climbing number of patients who have experienced FGMs.

Dr. Nawal Nour, the director of the African Women’s Health Center in Boston, was recently quoted in a New York Times article stating that information on FGMs in medical schools is “rare and random.” Nour said many of her patients experienced “a humiliating time with health providers” who were uneducated on how to manage them physically and emotionally.

“The worst thing a health care provider can do is wince or cringe or ask an inappropriate question,” she said.

With doctors ill-equipped to care for patients who have undergone FGMs, many women go untreated. This lack of education doesn’t aid the issue when combined with the social stigma of FGMs in a Western country.

Though the mere mention of FGMs is usually greeted with distaste and judging looks when brought up in front of Americans, we often fail to see the resemblance in our own culture. According to data released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2009, about 33 percent of newborn boys undergo circumcision.

But the difference between FGMs and the standard circumcision performed in the U.S. isn’t slight. While both are performed out of cultural practice and cosmetic purpose, most FGMs are rarely performed by licensed physicians with the correct tools. And anesthesia? Forget about it.

The CDC released guidelines in 2014 urging physicians to endorse the procedure after research revealed circumcision lowers risk of HIV infection by 50 to 60 percent, as well as other sexually transmitted infections.

To this day, there has been no medical evidence to support any form of health benefit by FGMs.

The Editorial Board believes the answer to these problems isn’t more cultural reproach and distance by disassociation. We’re not helping women by alienating them because of their customs. With the increase of women in America who have undergone FGMs, we should have more health care providers who are trained to serve patients who have had these procedures.

We have our work cut out for us. There’s no need to further the damage.