It is certainly the responsibility of school officials to protect students from content inappropriate for them in student publications, but clear lines must be drawn.

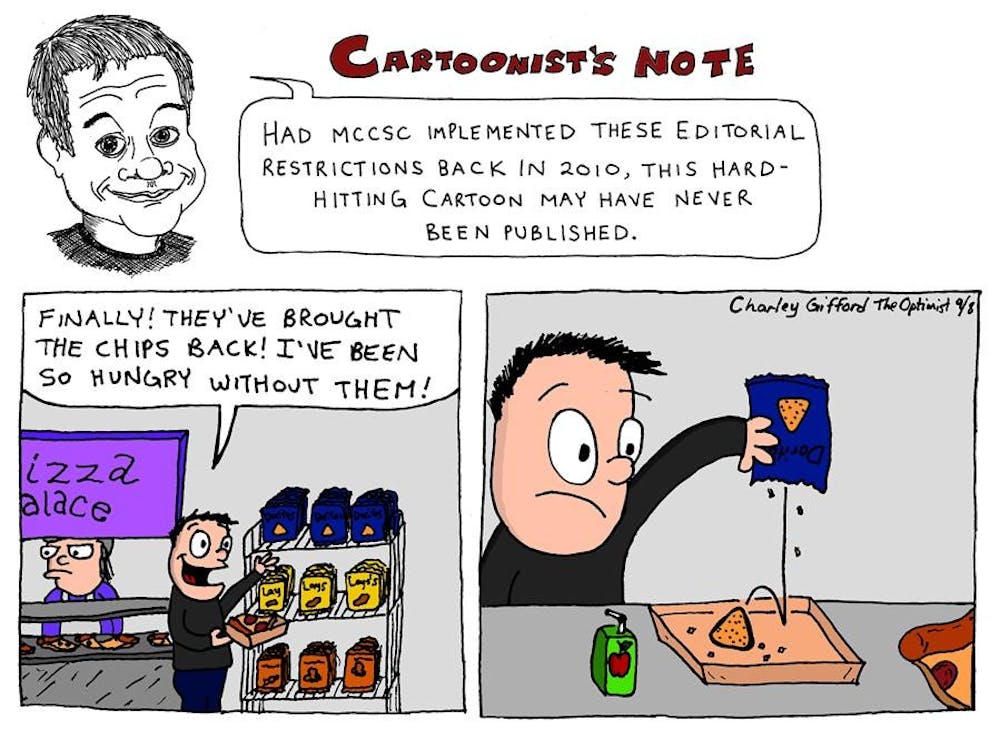

The student media policy currently before the Monroe County Community School Corporation Board of Trustees crosses these lines.

Policy 5722 would give the board unnecessarily broad rights to censor student media.

The policy states that schools have the right to refuse publication of materials that “advocate the use or advertise the availability of any substance or material which may reasonably be believed to ... contain obscenity or material otherwise deemed to be harmful to impressionable students who may receive them.”

This is not the ability to limit the publication of material it deems offensive, which the board gives itself earlier in the policy.

This is the ability to censor a publication merely for mentioning the existence of some other material completely independent of the publication that someone, somewhere in the school corporation has deemed inappropriate.

It is subject to an absurd and unjustifiable amount of interpretation by those responsible for enforcing it.

In 1988, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier that school corporations did not offend the First Amendment rights of their students in censoring student publications if doing so represented a “legitimate pedagogical interest.”

Policies of this broad nature — that preclude even mentioning the existence of offensive material — strike us as entirely outside the scope of any conceivable legitimate pedagogical interest.

The policy goes on to prohibit publications that “promote, favor, or oppose any candidate for election to the School Board or the adoption of any bond issue, proposal, or question submitted at any election.”

A school’s primary job is to give its students the tools necessary to be fully functioning members of their community.

An ability to deliberate and engage with political issues is certainly one of these tools. Limiting the ability of a school’s publication to cover precisely those political issues closest to it is not only outside the scope of a legitimate pedagogical interest, it is directly contrary to it.

In the introduction to policy 5722, the school board agrees to offer student media for students to learn “the rights and responsibilities of public expression in a free society.”

It then proceeds to list the many broad and loosely defined ways it plans to limit this model of public expression.

Restrictions that ensure students are exposed to appropriate content and give administrators clear guidelines about how to make these decisions are legitimate. But policy 5722 clearly does not accomplish this.

Removing its ambiguity and room for unilateral interpretation will safeguard the educational value of student media while ensuring students are exposed to material appropriate for them.

MCCSC student media at risk

Get stories like this in your inbox

Subscribe