I’ve had three different revelations about Maurice Sendak in my lifetime.

The first was around first or second grade. The school librarian had us all spread out on the reading-time rug, where we sat criss-cross, gazing up, open-mouthed at the story she had to share with us.

Sure, we’d heard “Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs.” We’d heard Dr. Seuss and Olivia the pig. But nothing had prepared us for the awe and terror that was “Where the Wild Things Are.”

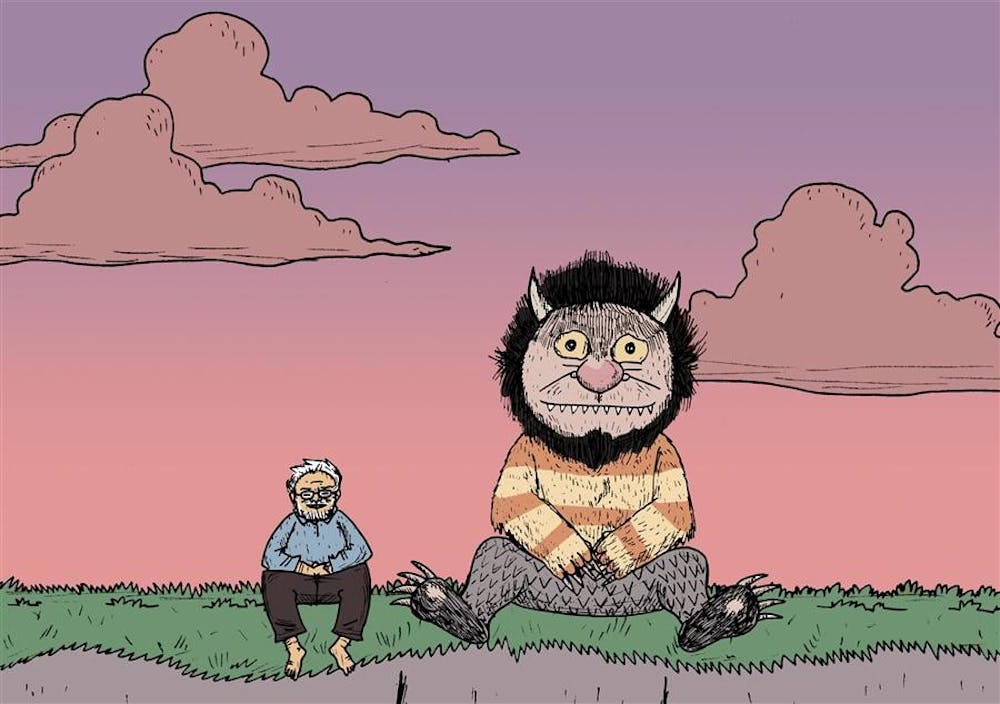

The illustrations were like engravings, violent and deep. The pages seemed to be veiled in low, nightmarish light. And the monsters — eyes rolling and claws bared — did not look friendly or approachable and promised no turnaround by the end of the story.

I am sure it wasn’t the storyline that made an impression on me. To be honest, plot development and complex narrative were of no import to Sendak when he wrote. Boy leaves home. Boy meets Wild Things. Boy comes back.

If anything, it was the lack of narrative “value” that stuck out. Max didn’t learn a lesson, nor did the librarian discuss a grandiose moral after the reading was finished. Max got away with being a destructive little shit and became king while he did it.

That’s what every kid wanted out of a book. We wanted to go on an adventure and not have strings attached. We wanted to look at pictures and laugh a little without feeling like we’d done something wrong when we got to the end.

My second revelation was in my senior year of high school. It was the day I graduated, and I was opening a gift from my then-boyfriend. I pulled the crepe paper away, only to find a fresh copy of “Where the Wild Things Are” with an inscription about growing up, moving on, yadda yadda.

I remember flipping through the book unfamiliarly, like I was reading it for the first time. And as someone who was not very moved by the graduation ceremony, nor phased by leaving my hometown, I started crying by the end. Like, sobbing hysterically, I would even say.

It wasn’t the pictures or the sense of departure. It wasn’t childhood nostalgia or profound realization of meaning within the text. It was the fear of moving on followed immediately by the comfort of coming back.

As an adult, being stuck in a state of immaturity isn’t something Sendak would reprimand. “Why is my needle stuck in childhood?” he once asked of himself. “I guess that’s where my heart is.”

Rather, Sendak was about reformulating childhood.

In my first year of college, I stumbled upon a pile of his works in a used bookstore in Lincoln Park, Chicago. These were ones overshadowed by “Wild Things”: “In the Night Kitchen,” “We Are All in the Dumps,” “Brundibár.” Even as a 19-year-old, I found them terrifying.

Sendak’s stories and illustrations provoked innuendos, and transformed nudity and orphans and Jewish history into subject matter for children’s books.

And then, there’s the realization upon watching interviews and reading features that he’s a cynic, a curmudgeon.

A sharp and unsentimental grouch who lives alone in the woods and is (gasp) an openly gay man! He disrupts our conventions of what a children’s author should be. In an interview with Stephen Colbert, Sendak said, “I don’t write for children. I write, and then someone says, ‘That’s for children.’”

His stories are an embodiment of the id. They are, as some would say, psychoanalytic stories of children’s fear, anger and comforts.

Sendak understood that kids already knew these things instinctively. “You can’t protect children,” he said, though his books were banned on that principle. He knew children needed literature that made adults uncomfortable.

But when you’re a grade-schooler sitting on a rug, that’s not what matters. What matters is the awed sense of inconsequential adventure, danger and immediate relief in the span of 48 pages.

Wild Side: Why Maurice Sendak was more than a children's author

Get stories like this in your inbox

Subscribe