In Indiana, health care options range from expensive to free. But for some people, even free health care is costly.

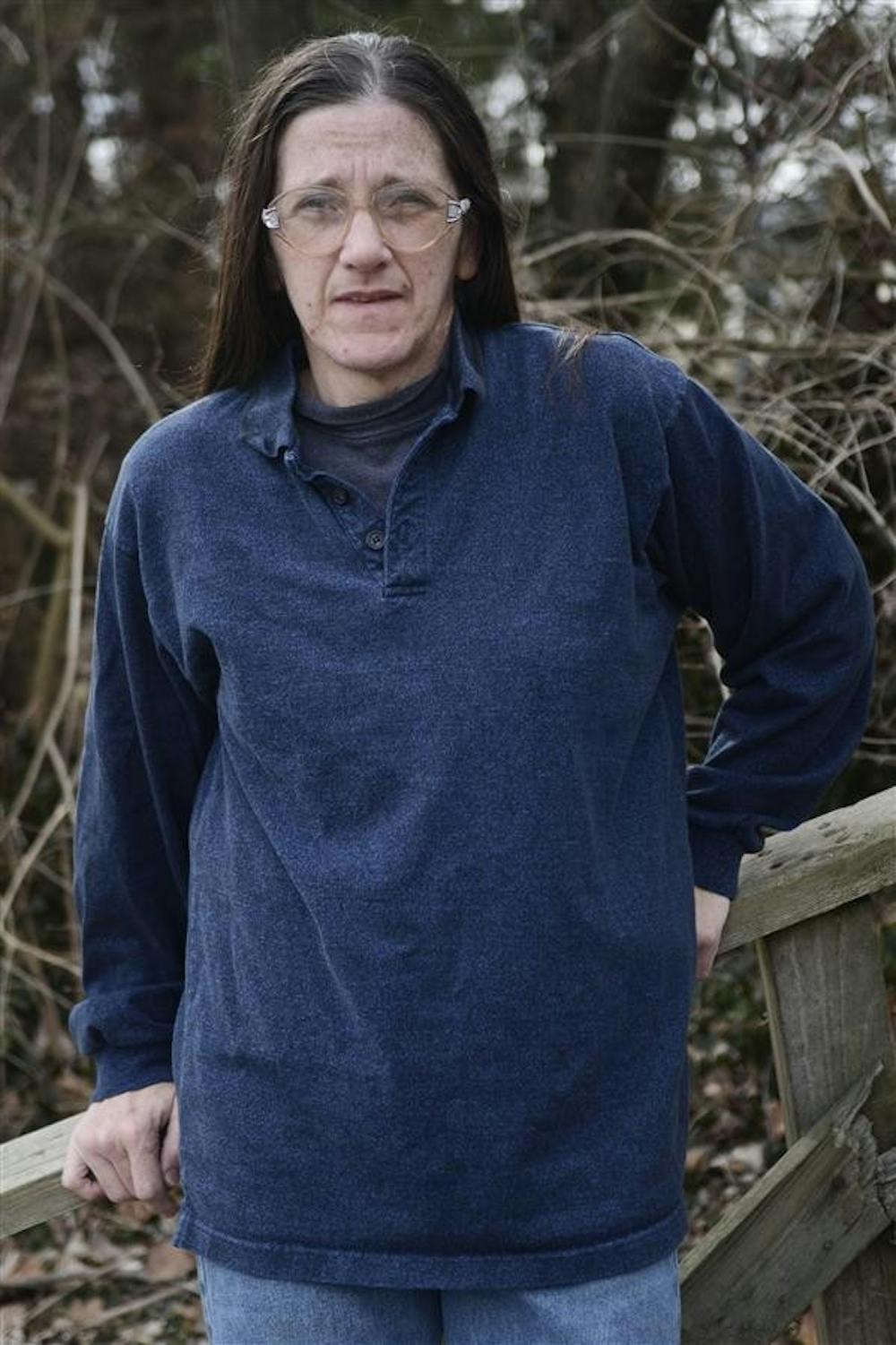

Lisa Haymaker, a 49-year-old Bloomington resident, does not qualify for state programs, such as Hoosier Healthwise or Healthy Indiana Plan. Her chronic illness, called degenerative disc disease, means that local free clinics — such as Volunteers in Medicine — fall short of alleviating her back and neck pain.

“I can’t walk too long, I can’t stand too long, I can’t sit too long,” Haymaker said. “I have to be really careful when I sleep.”

Haymaker’s disease is not very common, but only because it is not always considered a disease.

Degeneration of the discs along the spinal cord is a natural part of aging, said Dr. Paul Kraemer, spine surgeon at Indiana Spine Group in Indianapolis. But when static positions become painful, “degenerative discs” become “degenerative disc disease.”

“That’s actually pretty uncommon,” Kraemer said. “It goes from normal, healthy-looking discs to very significant degeneration, but it doesn’t have to be painful.”

Haymaker’s bone degeneration might have begun long before she received treatment, but in 2001 she fell and twisted her back while helping a patient with cerebral palsy at her job as a home health care worker. With the funding of employee-sponsored insurance, she visited a hospital where the doctor found she had a bone missing in her right ankle.

“After that, things just started going downhill,” Haymaker said.

Eventually, she had to quit her job and went on to work at more than five different jobs, some of which forced her to resign. She quit working altogether in 2005, the year she received an MRI, an imaging test that doctors typically use to study bones and joints. Haymaker has yet to pay the $1,800 for that single examination.

“Part of that time, I would go and they would say it was covered and I would find out that it’s not,” she said.

Until then, Haymaker’s bills were paid for by Workers’ Compensation.

In 2007, she appealed for Disability Medicaid and was denied because she had worked within the last 12 months.

“That’s not their problem, and that’s what I was told,” she said of the appeals process. “I said, ‘How am I supposed to live?’ They said, it’s not our problem.”

Scott D. Lewis, a lawyer in Indianapolis who specializes in disability claims, said most Social Security Disability Insurance applications are denied. Statistically, claimants are denied three times before they have a hearing with an administrative law judge, he said.

“That’s where the majority of the claims end up,” he said.

According to a USA Today article, one Social Security Administration judge denied 82 percent of 297 claims. The amount of disability-worker benefits in fiscal year 2010 rose 38 percent during the past five years, although the average waiting time for the review process has dropped steadily.

Indiana State Eligibility Manager Christy Johnson handles claims from Monroe County and said the only additional resources she recommends if claims are denied are the Healthy Indiana Plan or Volunteers in Medicine.

Since Haymaker makes too much money with child support from her ex-husband, she does not qualify for any of the state health plans, including Hoosier Healthwise.

To qualify for Disability Medicaid in Indiana, an applicant must also qualify for Social Security Income benefits. Haymaker’s incoming child support also makes her ineligible for SSI.

“They wait for natural selection,” she said. “If you’re too poor to afford it, you die off. Well, that’s one less person in the system. That’s how the system looks at it.”

The last time Haymaker received any form of medical care was the end of 2008. In her former hometown, Terre Haute, Ind., Haymaker frequented Saint Anne’s Clinic, where general practitioners offered services for just a $20 visit charge.

The clinic was open two days a week for eight hours. People waited in lines down the block for the small chance of getting into one of the 20 spots the clinic had available.

“It can be very difficult to give access for everybody and to see somebody who can really give them good advice on what needs to be done,” Kraemer said. “I think the bigger issue is access to specialists for people without very good insurance.”

Kraemer said about two-thirds of spinal care providers in Indiana won’t see Medicaid patients because Medicaid is a hassle to deal with and pays doctors poorly.

“It can be very difficult, and there is no good solution,” he said.

Haymaker said her contact with disability lawyers has not been altogether positive, but she plans to file for SSI again and contact local lawyers.

“You have no choice,” she said, smiling. “If you can’t make it, you save your money until you can buy it, and if you can’t do either one, then you make do with what you’ve got. You do what you can, and that’s all you can do.”

Disease makes resident ineligible for state support

Get stories like this in your inbox

Subscribe