Editor’s note: University of Missouri System president Tim Wolfe stepped down today after football players went on strike due to Wolfe’s lack of response to racial incidents on campus during the past few months. Faculty members also threatened to walk out. In 1969, IU football players protested against racism. They were kicked off the team.

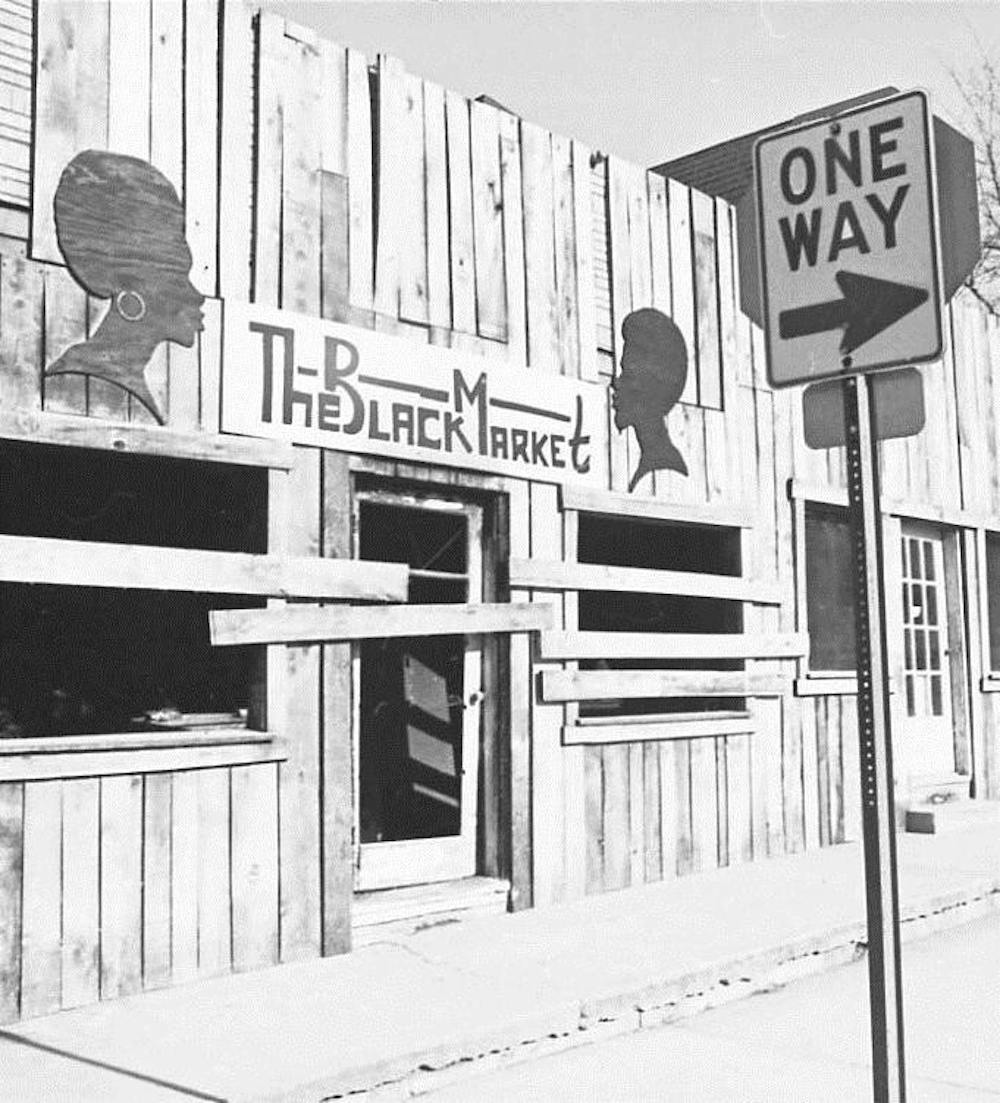

One-hundred-and-fifty black students burst into an administration meeting in Ballantine Hall and held faculty members hostage for three hours. A sit-in shut down Little 500. Ku Klux Klan members firebombed the Black Market. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated.It was the late 1960s in Bloomington, a story that is nearly forgotten. Orlando Taylor, then an IU assistant communications professor, was a key player in these events. He remembers.On the evening of Thursday, April 4, 1968, Taylor was having dinner with his family. The newscaster on television relayed statistics of the Vietnam War. Then the news broke that Martin Luther King Jr. was shot and killed.King didn’t even make it to the hospital before being pronounced dead. Taylor jumped up from the dinner table. “Oh no,” he thought. “They shot him. They shot him down like a dog and he’s for peaceful ways. Lord, help the rest of us.”With his wife and children’s eyes on him, Taylor walked out of the house to his car. He drove and hours passed. There was no destination in mind.He came home, still distraught.The recollection still pains him, more than 40 years later. Taylor removes his glasses and wipes his eyes.“Martin Luther King was saying, ‘Let’s hold hands, let’s make peace,’” Taylor said. “If that’s not acceptable, then what would be? I thought then and there that peaceful protest in America would die.”King’s death spawned a series of riots from Chicago and Detroit to Washington D.C. and Los Angeles. Also, youth were taking to the streets and making their voices heard in unprecedented ways.Southern Indiana, typically known as a hotbed for conservative and patriotic thought, did not take kindly to such unrest.Historically, an active Klan and overt racism plagued Bloomington’s surroundings.Edwin Marshall, the current vice president of diversity, equity and multicultural affairs, said his freshman introduction to IU took place at a cross burning he stumbled upon while with friends at Griffy Lake. Just walking on campus, Marshall said, as a person of color, it wasn’t uncommon to be the victim of a drive-by racial slur. When the news of King’s assassination hit campus, students were angry, afraid and ready to fight for change.Talk Is CheapBy May 1968, just weeks after King’s assassination, cabin fever had set in for IU students. It was the eve of Little 500, the University’s renowned bicycle race week, regarded nowadays as “World’s Greatest College Weekend.” Women arrived in shorts and tank tops, and men shed their overcoats. The exams to follow were being prepared, and students were missing class.Little 500 Weekend was a chance for a handful of black students to make the University climate more inclusive for them. This meant getting the University higher-ups to push for traditional efforts of recruitment and enrollment of students of color. This also meant an implementation of a black studies program.Herman B Wells, the University’s beloved chancellor at the time, had set the tone by integrating the swimming pool and refusing patronage to local business that practiced segregation.Still, Taylor said things weren’t moving fast enough.“Everything was like a task force,” Taylor said. “You get everything to a committee, submit your appeal and wait.”Black students were tired of waiting. A recent visit to IU after King’s death from then-presidential candidate Bobby Kennedy rejuvenated students in the fight for social justice.Taylor said it was then that idealism had begun to take hold. Change needed to happen.Taylor said that students felt disrupting Little 500 was a major way to get attention from the news media and the University.At the time, Little 500 was a mostly white fraternity event.So, armed with blankets and bologna sandwiches, 50 black students marched to the racetrack and sat there.“We shall not be moved,” they sang.Taylor remembers going to the track with then-IU President Joseph Sutton. It was raining. Even with soggy bologna sandwiches, students were still singing and holding on to one another. Someone held an umbrella over Taylor and Sutton, who addressed the students.“Go home,” Taylor said, recalling Sutton’s words. “I promise, if you make a plan, a solid proposal to put what you want into action, we will take it seriously. But, please just go home.”The students left the track at dawn with renewed hope. Sutton was a leader for the change they wanted, and Taylor was a voice of reason, a liaison. The students got the media coverage they wanted, and a promise from the president of IU to make things more welcoming for blacks.The spring 1968 semester ended. Change seemed more possible than ever.MomentumWhile students were away for summer vacation in 1968, Bob Johnson and Rollo Turner, black graduate students who would later lead the charge, began drafting a proposal as Sutton requested.The proposal primarily called for the implementation of a black studies program and the addition of more black faculty members to other academic departments.By fall of 1968 it was completed and released. It was a 10-page document for a comprehensive program to reform the way IU looked at its black students.Taylor said Turner, Johnson and himself were invited to a conference in Washington, D.C. The proposal set a model that other universities would soon follow.“In Indiana we became somewhat famous,” Taylor said. “This is something you’d expect of a more urban campus, Berkeley or Madison, for example. I think people saw it as black students, not just civil right activists, were proposing change, comprehensively.”Also at that time, an attitude of black consciousness set in at IU.“Not Afro-American or Negro,” Taylor clarified.Black consciousness, as embodied in attitudes and fashion. Natural hair was in and there were no places in Bloomington selling black hair products.“Then, it was Revlon and stuff that did nothing for our hair,” Taylor said.Turner and a few other students secured a University grant to build the Black Market on the northeast corner of Kirkwood and Dunn Streets. The Black Market specialized in what was missing from other Bloomington businesses. Aside from hair products for natural hair, it sold black music – jazz and rhythm and blues. It sold incense and African literature, too.Apart from what it sold, the Black Market stood as a proud representation of black students’ progress in establishing social equality.Peoples Park stands there now, in memorial to the many protests held after the Black Market was ruined.There was something else in the air, however.Black students began complaining of ominous phone calls. Taylor recounted a fall day he was returning home from classes when he saw a note tacked on his door. The message appeared to be etched in blood.“Be careful, nigger. If I were you I’d get out of town.”Despite hovering tensions, no one knew what would happen next.December 26, 1968It was seven minutes to midnight. IU students were away on holiday break. A man described in reports as wearing a gray trenchcoat, about 5 feet 6 inches tall, 150 pounds, approached the Black Market. His male accomplice drove the getaway car.He hurled a Molotov cocktail through the west end of the building. The cocktail was a kerosene-filled glass jug once used for milk.The windows shattered. The place shot up in flames.Taylor said the Black Market fire brought something openly violent to the community.“It was a setback from what we were trying to accomplish,” Taylor said. “There was an undercurrent of hatred, rednecks who were determined that change was not going to take place.”According to an Indiana Daily Student article, the morning after the fire, Dec. 27, a blonde student stood in the Black Market rubble. “Now I suppose black people will blame all whites for what has happened here,” he said.Taylor said building founder Rollo Turner also visited the Black Market after it was bombed. He could smell the burning cinders.A sea of burned books was left in the debris with pages open. Part of a Langston Hughes poem was visible.And a banner on what was once a front window of the Black Market said: SHAME.A protest was held in the cold air on Jan. 10, 1969, upon the students’ return to campus. About 200 black students gathered in front of what was once their haven.There was a makeshift stage in front of the rapidly growing crowd.In the local newspapers reporters wrote that the bitterness of black students would be expressed in God’s law: “with an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth.”Black students were, as Taylor put it — mad as hell.‘Riot Gear’The stakes were raised for student action in spring 1969. Efforts to rebuild the Black Market died out, and black students gave up hope of saving the only place in Bloomington that was truly for them.Further complicating matters, a proposal of a 68 percent tuition increase, to be in effect the following fall, brought student rage to a boiling point. This threw a wrench in black students’ desires for a more inclusive — and more affordable — campus.On May 6, 1969, 3,500 students from IU and four other state campuses marched peacefully at the Statehouse to protest the increase. Between 30 and 50 percent of students boycotted classes in Bloomington.Meanwhile the Black Market arson, a case which was still under investigation, was the metaphorical gasoline to the campus controversy.The black students’ response to the tuition hike was the torch, the escalation, the ignition.“People just got really antsy,” Taylor said. “No one heard much after the initial announcement of the tuition raise. We all thought the University was trying to bide time until the students were away for the summer.”Enough was enough. Marshall said he remembers campus police riding around with their guns as if they were prepared for the worst.A leaflet found in front of Owen Hall warned IU students of potential backlash from the administration and what to do should police get involved. It included instructions such as “don’t panic” and “if you are tear-gassed, do not rub your eyes.”A faculty and administration meeting addressing students’ concerns about the tuition raise was planned for 10 p.m. Thursday, May 8, 1969. It was in the Faculty Lounge of Ballantine Hall.News reports and personal accounts vary, but the facts are that around 11:20 p.m., about 150 black students burst through the doors of the Faculty Lounge and initiated a lock-in that would last for three hours, or until the Board of Trustees honored a meeting with them and discussed a rescinding of fees.Taylor said five football players locked arms in the entrance and would not allow faculty to leave.In a tape-recorded transcript of the incident, concerns were raised about the safety of the faculty members and the students’ intent. It is unclear who is speaking at most points, but it can be determined from the transcript that the situation at hand was potentially dangerous.Part of the transcript reads, “Are you safe there? Is the telephone safe? Yes. What these kids may or may not realize is at this point they have 90 percent of the elements of kidnapping going, which is a capital – I don’t suppose they give a damn, do they. They claim they don’t.”Taylor said he was called upon as a faculty member to diffuse the situation. Taylor wasn’t involved with the students conducting the lock-in, but he was associated with them because he was an advocate for their cause. He said David Derge, Sutton’s right-hand man, pointed at him and said, “You better tell those students they better leave.”Taylor responded, “No. You better listen to them. The fact that the students would even be driven to this is something you can’t ignore.”After three hours, though, the police could be heard outside. Derge had escaped through a window and alerted them and President Sutton. Taylor could see officers in “riot gear,” shielded by breastplates and armed with billy clubs.Taylor pleaded with the students. “Leave,” he told them. “This ain’t worth getting heads busted. The police are here and ready to fight.”He was worried for their safety, but his own reputation was also on the line. Sutton was ready to offer Taylor the position of vice president for the office of diversity, equity and multicultural affairs, a position that would have surely gotten all the students a step closer to the leverage they needed.The students went home, but nine, known as the “Bloomington Nine,” were served with subpoenas a few days later.One of the nine individuals was Taylor. The even-tempered voice of reason was now involved in a grand-jury indictment for charges of conspiracy and rout.Ironically, the “rout law” used against the “Bloomington Nine” was the same state legislation enacted to control Ku Klux Klan activity.As the Bloomington Nine trial continued, arrests were made in connection to the Black Market arson.Briscoe confessed during interrogation that he and a male accomplice committed the crime. On Aug. 6, 1969, 26-year-old Carlisle Briscoe Jr. and 27-year-old Jackie Kinser were booked and charged with second-degree arson. Briscoe pleaded insanity, and Kinser didn’t enter a plea at all.Both men admitted they were Klan members. By September, Briscoe was found guilty and sentenced one to 10 years at a state facility.The Bloomington Nine didn’t spend any pre-trial nights in jail because several professors, including then-English professor Philip Appleman, put up their houses for collateral for their bail.“Indictment,” Taylor said. “Reasonable evidence that you might have committed a crime.”Thomas Berry, who was the case prosecutor, asked Taylor if there were threats made during the incident, Taylor said.There was a sea of people in the faculty lounge that evening, he said. There were suddenly even more eyes on him than before; this time, he said, he was being observed not as a leader, but as a criminal. The courtroom seemed to swirl.“They wanted me to name people who were involved,” Taylor said. His voice cracked and his eyes flicked back and forth like a metronome. “I had an instant case of memory lapse.”QUIETBerry threw out the case in August 1971. At the same time Jackie Kinser’s arson charges were dropped. He and Briscoe disappeared.Nevertheless, a sense of peace seemed to be restored.There were lasting consequences for Taylor. He was withdrawn from consideration for the position of acting vice chancellor of IU because of the Ballantine Hall case. He left for Washington, D.C., and now travels between there and Chicago as president of the Chicago School of Professional Psychology.He is the only person from the Bloomington Nine who can still tell his story.Turner left IU without completing his degree to take a job as a professor in the newly founded black studies department at the University of Pittsburgh. He died of a heart attack at age 50 in 1993, while riding his bike home from work.Little is known about what happened to other black student leaders. Most of the original Bloomington Nine are dead now, sources say.Taylor said the few days after the Bloomington trial were rainy ones. Black students began having more meaningful conversations with faculty members about their hopes, their feelings, their dreams and aspirations.It was the first time during his time at IU, Taylor said, that there was a period of genuine reflection. The madness that had gripped campus, and the nation, was beginning to calm, too. It was 1971, and though times were still hard with Vietnam, equality for all seemed more possible than ever. There was finally, at least for a short time, a sense of peace and quiet.“Not silence,” Taylor said, “but quiet.”