A single line sits idly on an empty screen in Disney’s classic film “Fantasia.” It is soon given life, emotion and expression by a symphony in a flurry of color and light.

Such is the art of animation.

“Simple lines and shapes can move and be expressive of how humans move. Animators can extract that human quality and bring them into the world of these abstract elements,” said Andrew Bucksbarg, an assistant professor in the telecommunications department. “As an art form, it’s really vibrant and exciting.”

Bucksbarg is an experimental animator himself. Through his own manipulation of sound and color, he has created what he feels are minimal but expressive works of art that emulate the full range of human emotion and movement from its most realistic to its most abstract.

What Bucksbarg and countless other animation artists are doing today is not typically associated with the cartoons that amuse and educate children, but Bucksbarg knows there is a relationship between the experimental and the mainstream that drives their craft.

A good animator has a familiarity with the body in the same way a dancer would, Bucksbarg said, and an artist can spend years studying how something moves until they get absorbed by the mainstream culture. We see their work in films, television and advertising, then they use what they earn to fund their own independent projects.

Communications and culture graduate student Laura Ivins-Hulley said people usually associate animation with cartoons on television or mainstream products by Pixar and Disney.

“Every now and then, someone will think of the art and claymations, but it’s fairly limited in how people imagine what animation looks like,” Ivins-Hulley said. This becomes a problem when animators seek funding. If they get it, they’re limited to shorts rather than features.

This wouldn’t have been a problem in the heyday of Hollywood, when animated shorts were packaged along with feature-length A-pictures. Now that market has moved online, and with the advent of computer animation technology, artists are capable of a wealth of new innovation but are unable to break into the dearth of big-budget cartoon features.

“I wish it were more feasible to be a short filmmaker,” Ivins-Hulley said. “I’ll see these really beautiful, imaginative, short animations from some 22-year-old student at CalArts who’s just starting to figure out who they are as an artist, and the person will disappear into Pixar.”

Leslie Sharpe, an associate professor of digital fine arts, knows of the full scale of successes and failures of modern animators from her students and inspirations.

“Animation within the art world has always been practiced by very important artists but has always been marginal in terms of its reception,” Sharpe said. “More recently, you see a lot more inclusion of animators as artists in galleries in very prominent ways.”

Much of that, Sharpe said, is because of YouTube and other ways of immersing oneself in culture on the Internet. Two of her students were selected as part of the Guggenheim Museum gallery because of their work they posted on YouTube.

Because of these tools to distribute art and animation widely, animation is highly prevalent in today’s culture, and educators are developing new techniques to reach kids using animation as an active tool in the classroom.

“Children are immersed in a media-rich world, and these animated shows make up an important linguistic and cultural resource for children,” said Karen Wohlwend, an assistant professor in the Department of Literacy, Culture and Language Education of the School of Education. “There’s been quite a push in the last 20 years to open up classrooms to use these texts that they know and love and look at the ways that enriches their writing and reading, but it’s also to help them think critically about where these things come from and who makes these texts.”

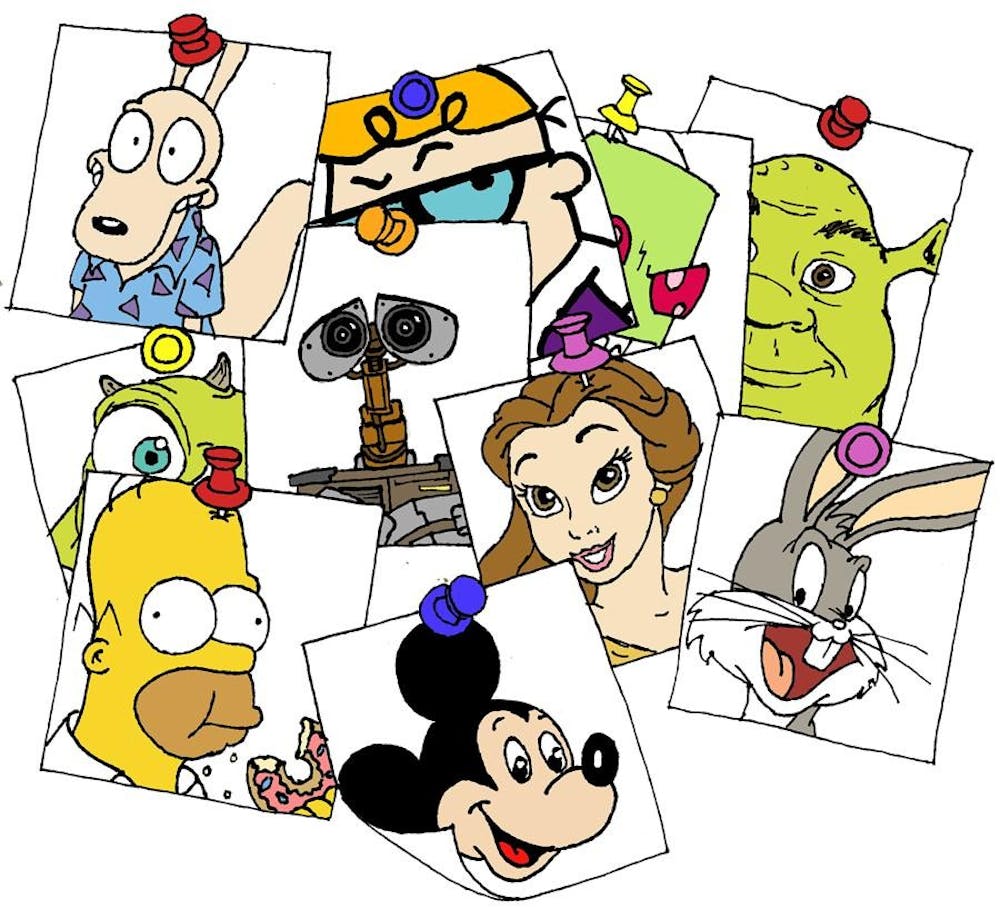

Arguably, children are not the demographic for experimental forms of animation, but if adults created a market for inventive short films the way they once did with Mickey Mouse and Bugs Bunny shorts, experimental animation may be right for kids after all.

“It appeals to children for the same reason it appeals to us,” Wohlwend said. “Children take up these films in pretty complex ways. Cutting them off altogether would be impossible. What we want to do is teach them to respond and be selective in making choices, and we can assist with that.” Wohlwend explained that parents are highly influential in shaping children’s opinions on media because kids can easily pick up about their parents’ feelings.

Their education becomes part of a give-and-take process between consumers and animators. Ivins-Hulley has found in her study of stop-motion films from the Czech Republic that existing animation typically draws from a society’s already established visual culture.

Ivins-Hulley’s idea relates to Bucksbarg’s own dilemma of choosing between “showing a character” and “making them real” in his own animation.

“Sometimes something not fully human is even more human,” Bucksbarg said.

Animation as art goes beyond mainstream

Get stories like this in your inbox

Subscribe