Tommy John surgery.\nIt’s a term thrown around a lot in modern-day sports circles, a sort of “wonder cure” for pitchers unfortunate enough to tear their ulnar collateral ligament, a band in the elbow necessary for throwing at competition speeds.\nMajor League All-Stars such as John Smoltz and Mariano Rivera have undergone the procedure, returning as strong as or better than they were before.\nBut when senior right-hander Chris McCombs, a pitcher on the IU baseball team, had to undergo the procedure at an alarmingly early age – his junior year in high school – he certainly didn’t see it as a medical miracle.\n“It sucks,” said the Louisville native, who said he thinks arm overuse probably contributed to his injury. “That summer that I threw before the season, I was pitching in it seemed like every game.”\nAnd McCombs isn’t alone, at least not according to Dr. Dale Snead, an upper extremity surgeon with Methodist Sports Medicine. Snead estimated that he performs something in the ballpark of 20 Tommy John procedures each year, and he sees more than 100 patients for elbow trouble each year.\n“I saw two today,” Snead said Wednesday night.\nOnce reserved for professionals, Tommy John surgery is becoming a more widespread option for high school and college players – especially pitchers – seeking help with elbow problems.

How it happens

McCombs said his first injury came on suddenly, though he still thinks overuse is the reason for the injury.\n“It was kind of a freak thing,” McCombs said. “It was like a one-pitch, ‘Wow, something really is wrong.’”\nSurgery is required when the ligament becomes damaged to the point that it creates what Snead termed a “deficiency” in a pitcher’s throwing ability. He said the ligament doesn’t always tear, but he said it cannot be repaired, only fully reconstructed.\nThere are several different factors that can lead to the ligament damage.\nFor example, McCombs also said he thinks his decision to begin throwing breaking balls at the early age of 11 might have had something to do with his arm breaking down. But Snead said thus far, no data has empirically proven that throwing breaking balls too young has an adverse affect on the elbow. He did say, however, that evidence does back up the theory that bad mechanics in a pitcher’s delivery can be devastating for the ligament.\nSnead said a pitcher’s arm endures a stress of about 7,000 meters per second when delivering, so having a poor or unhealthy release could be a factor in potential ligament damage.\nThat’s what happened to McCombs’ teammate, sophomore left-hander Jason Ferrell.\nIn March 2007, Ferrell was learning to throw a different version of his change-up. Ferrell said that change, coupled with poor arm care on his part before and after starts and workouts, caused ligament damage that required Tommy John surgery.\nHowever, Ferrell said one look at the test results scared him enough to get him to work through rehabilitation and practice better arm care.\n“When I actually went down and got the MRI taken, it was a big shock to me,” Ferrell said. “It was like someone telling me I wouldn’t be able to do something I love for the rest of my life, because you’ll never know if you’re not going to be able to come back the way you were.”\nIU pitching coach Ty Neal said mechanics present a problem for coaches looking to prevent elbow injuries. He said there are players who have success using “unorthodox” wind-ups, and it’s hard for a coach to change those throwing mechanics sometimes.\n“If they’re having success, it’s tough to say ‘Hey, you need to change this,’” Neal admitted.

How it's done

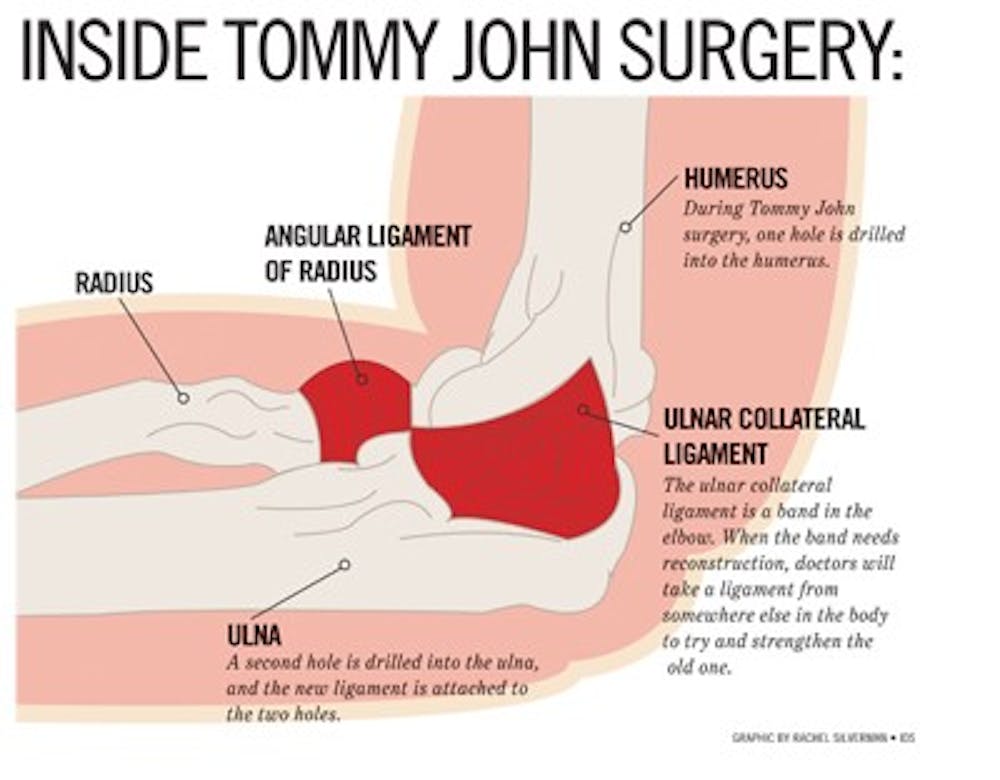

Essentially, Tommy John surgery consists of taking a ligament from somewhere else in the body and putting it into the elbow. Holes are drilled in the ulna and the humerus – bones that meet at the elbow – and the ligament is then secured to the bone.\nSnead said the new ligament is generally not meant to replace the damaged one. Rather, the fixation of the new ligament simply “beefens up” the old one, or so doctors and patients hope.\nSnead said the chance that a patient recovers and comes back from the surgery as strong as or stronger than before are higher than ever. He said he believes that increase is because of in-depth, procedural research. \n“The challenge became one, can we make the surgery a little bit easier, and two, can we get fixation back stronger,” Snead said. “I think we’re better at it than we were 10 years ago.”\nLigament damage is becoming a significant problem for an increasingly younger population, Snead said.\nWhile he doesn’t think the number of surgeries has increased, Snead said he believes he has seen an increase in the number of young players he treats for elbow ailments similar to ones that would require a Tommy John.\n“Far more people are seen for the problem than need surgery,” Snead said, “partly because it’s a pretty lengthy recovery process.”\nAfter the procedure, Snead said doctors and trainers put players through a disciplined rehab regimen, which begins with shutting the arm down completely and then slowly working the pitcher back up to pitching full-time.

What's to be done

McCombs said he believes everything starts with better communication between coaches and players, though he’s not sure how best to go about that.\n“I don’t know the best way for that to be handled because as a player and a competitor, when your coach comes to you and says ‘Can you go?’ it’s kind of your natural reaction to say, ‘Yes,’” McCombs said. “You want to play.”\nNeal also said he thinks part of the problem might be genetic.\n“I would say in some instances kids are being abused,” Neal said, “but in other instances, I think we’re all prone to break down at some point. Some probably breakdown at 15, a guy like a Roger Clemens may never break down.”\nAnd it’s not just injuries causing these problems. Ferrell said when he went in to have his procedure done, another young pitcher was waiting at the same time.\nThe twist? There was nothing wrong with the kid’s arm – his father simply wanted him to have the surgery in hopes his arm would come out stronger afterward, something Ferrell said shocked him.\n“If a kid’s actually injured and he needs to have the surgery, that’s the only time he should have the surgery,” he said.\nNeal said having the surgery can even hurt a player’s chance of winning a scholarship, depending on when he had the procedure done.\n“We don’t want to inherit an injury or inherit someone we’re going to have to rehab for a year and hopefully they bounce back,” Neal said. “So from a recruiting standpoint, you just walk away, unfortunately.”\nFerrell cautioned against using Tommy John surgery as a fall-back. He said that, while it lit a fire within him and made him more committed to taking good care of his arm than ever before, most pitchers should practice prevention first and always.\n“It worked for me, but it’s not going to do the same thing for everybody,” Ferrell said. “I recommend it, but at the same time, kids just need to take care of their arms, and they’d be a lot better if the surgery wasn’t necessary so often.”